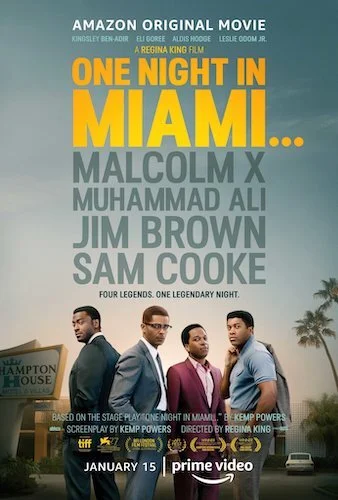

One Night in Miami

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Regina King has always felt like an artist who never quite was doing what she was fully capable of, despite her successes. Take a look at her early work with John Singleton, or Ray, or the other handful of examples, and you have a raw performer that understands the cinematic medium very well. Stuff like Legally Blonde or Miss Congeniality (both sequels, by the way) or Daddy Day Care just wasn’t showing her depth. Finally, the current wave of King’s dominance over film has begin. The spark her career needed came in the form of If Beale Street Could Talk. Barry Jenkins’ wonderful followup feature to Moonlight — the latter being acclaimed on all fronts — was loved, but most viewers could agree on one thing: King steals the entire picture. A year later, she headlined Damon Lindelof’s breathtaking miniseries Watchmen. At this point, there’s clearly no turning back. King will finally be getting the work she’s been deserving of.

This rejuvenation couldn’t have come at a better time. Regina King just hit fifty years old last Friday (an accidental coincidence, considering one of her early film roles was in a film of that same day of the week, but let’s not reach too much now). Her feature film directorial debut One Night in Miami was released worldwide via Amazon Prime on that same day as well. Her present to herself was her ability to show the world what she could do behind a camera (outside of the numerous television shows she has directed for, of course). Her interpretation of Kemp Powers’ creative play is the culmination of everything she has learned throughout her career (Powers also wrote the screenplay for this film). In ways, King is a passive filmmaker that lets the story and its subjects do the talking. At the right moments, King steps in to punctuate moments, proving her expertise on the cinematic language. You can tell very quickly that One Night in Miami was made by a knowledgable filmmaker, and that you are in good hands for the next two hours.

The four historical figures blend into the hotel throughout the film, as if the setting was its own character.

One Night in Miami is far from a biopic or a tale that is meant to be taken as truth of any sort. It’s a hypothetical scenario: what if four of the biggest names in pop culture spent this evening together? What would they talk about? Would they quarrel? You’ve got a squad of legends of different fields, all experiencing major turning points in their lives. Cassius Clay is converting to Islam, and is ready to announce that he now goes by Muhammad Ali. Jim Brown is aspiring to break out of football and get into acting. Malcolm X is stuck in the middle between his intense teachings, and a change of heart he is catching glimpses of. Sam Cooke is wanting to dominate music outside of just making successful pop songs; he has a moment where he compares himself to Bob Dylan, and wonders “what if?”. Together, we get a very unique picture, which acts as an amalgamation of numerous similar films: a fuller Insignificance, a more dramatic My Dinner with Andre, and a relative of the Before trilogy with a wider cultural impact.

Just hearing these four figures talking with one another is great enough, especially because Powers and King exhaust any possible connection (the four icons also get alone time, or more personal discussions with each of the other icons, showing a whole range of chemistry-based dynamics). When One Night in Miami chooses to get bombastic, it slowly generates its tension naturally, keeping the illusion of this “real” scenario alive. Not only are these four people experiencing their own thresholds: they’re also living an important time in American history, with racism being a massive talking point during a scorching political climate. Things won’t just be all roses and sparkles. One Night in Miami knows this, and approaches the possibilities just right.

The more serious moments prove to be gripping, even though this is clearly a work of fiction, proving the attention-grabbing strengths of the picture.

The hotel that One Night in Miami is set in also feels like a character of its own. Each time we are taken to a different portion of the building, it feels like we’re in a different phase of the film. The rooftop feels dangerous, and some reckless behaviours happen there. A hotel room is claustrophobic, with some of the more personal conversations and confrontations taking place. The bar is populated, so the iconic figures blend in with the people and the vibe of the ‘60s. It’s abundantly clear that this is a film that is based on a play, but it doesn’t even matter, given how impactful each transition feels; it’s a clever use of limited settings. Within these small spaces are the four actors that bring life to these famous faces of yesteryear. Kingsley Ben-Adir does his best to not be anywhere near Denzel Washington’s take on Malcom X, and he succeeds with his own interpretation. Eli Goree has that youthful charm (verging on arrogance) that Cassius Clay would have, bringing a familiar realism to this role. Aldis Hodge is a listening Jim Brown, who observes as much as he can, and carries a stoic, pensive demeanour (he acts almost like the anchor of the four).

Then, there’s Leslie Odom Jr. as Sam Cooke, and I cannot think of a better casting choice for a real person within the last few years. As far as I’m concerned, absolutely no one should even be in the conversation for the Best Supporting Actor awards of any ceremony this year. Odom is perfect as Cooke, first of all. He replicates all of his little nuances, hand gestures, glances and postures so naturally. I rarely say this, because I’ve watched enough films to be disillusioned to the magic of biopic performances, but I honestly felt like I was watching Sam Cooke back from the dead at moments; this is especially true during his performances, which are still stuck in my head, as I try to fight these memories off to prevent myself from getting emotional. Sure, we knew Odom can sing, but perfectly embodying Sam Cooke (even with his singing voice) is a slice of acting perfection that has helped pull the slower 2020 film catalog from out of the mud. I’m going all out and declaring Odom as Cooke as my current favourite 2020 performance. He’s equal parts commanding as he is exquisite to watch.

Leslie Odom Jr. delivers one of the finest performances as Sam Cooke in One Night in Miami.

It only makes sense that it’s Odom’s brilliant Cooke that wraps up One Night in Miami. Cooke would go on to write one of the greatest musical commentaries in the form of “A Change Is Gonna Come”: a song about the perseverance of African Americans to encourage civilization to break out of the strangleholds of prejudice in the United States. In a film about the defining chapters of four black icons, Cooke’s grand finale is especially relevant. We view the events after this fictitious crossroad (these followups are real, of course), ranging from Malcolm X’s house being set on fire as he completes his legendary autobiography, to Brown’s retirement from the NFL. We don’t need to see much more from Cooke, who sings his heart out on The Tonight Show (Cooke would face a devastating demise in reality, having been gunned down at the age of 33). This marks his realization after One Night in Miami, and his dream of being culturally relevant as a voice of the civil rights movement coming true.

In the same way that these four characters felt the breath of a racist America on their necks and felt the need to take action in their own way, Regina King does just this with One Night in Miami: a sensational breakthrough for the first time film director. The political climate is just as heated now (if not more so), and the call for such a picture couldn’t have been more appropriate. Even outside of its social poignancy, One Night in Miami is a straight up well crafted picture that uses its restrictions in the best ways it honestly could have. Few leads and few settings don’t mean a thing, here. The film is still larger than life itself regardless. Tossing such magnificent figures into a room is usually the basis of a joke or the failed experiment of a dreamer. Kemp Powers’ game changing play was just the blueprint for what King set out to do: give these rooms all four walls that we’re intruding in on. We feel like we’re a part of something massive, and King succeeds in making this event feel massive. If One Night in Miami is how she’s starting out as a filmmaker, I cannot even fathom where she is going to go from here.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.