The Hours

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Today is Virginia Woolf’s birthday. So, here is a review of The Hours.

I won’t beat around the bush. I’m not the biggest Stephen Daldry fan. When it comes to anything from 2008 onward, I feel like he gets carried away with the individual elements that create award winning films (like music, performances, and lines of dialogue) whilst losing sight of the bigger picture. Works like The Reader and Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close feel so disingenuous, as if they are being yanked by the glory of Oscar gold; given their subject matters, that’s a little worrisome, I feel. Then you have Billy Elliot, which was Daldry’s big breakthrough, and a passionate picture that felt organic; it’s a little conventional, sure, but its heart is very pure.

The Hours feels like Daldry’s most ambitious project without overstepping his boundaries, and I feel like the picture is all the better for it. It is divided into a triptych of stories, all surrounding women and their facing of society in their individual times (the stories are cut together, so we hop from timeline to timeline, and see the creative narrative juxtapositions Daldry and company have made). We start with Virginia Woolf (in 1923), who is working on her classic Mrs. Dalloway and is contemplating suicide. Mrs. Dalloway then passes through time and lands in the laps of two women down the road. In 1951, Laura is struggling within the confinements of the expectations of the nuclear family. Clarissa Vaughan lives a progressive lifestyle in 2001, and acts as the living, modern equivalent of Mrs. Dalloway herself (also named Clarissa, mind you); Laura from the previous story is the mother of Clarissa’s partner, here.

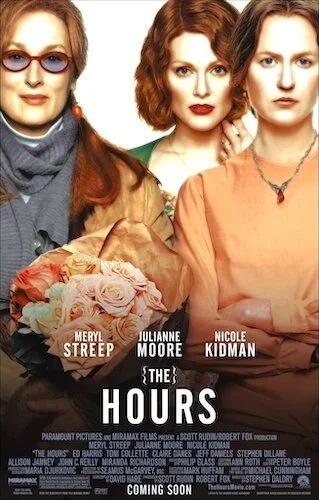

Nicole Kidman soars as Virgina Woolf.

For all three women, we needed a strong cast. Who better than Nicole Kidman as Virgina Woolf (ultimately her Academy Award winning role), Julianne Moore as both versions of Laura Brown, and Meryl Streep as the reincarnation of Clarissa? Toss on an even bigger and versatile cast (Ed Harris, Toni Collette, Miranda Richardson, John C. Reilly, and many more), and you have an unbeatable recipe for this picture. So, how does it fare out? Daldry actually hits The Hours out of the park, using each story — concocted, real, or metaphysical — so effectively. You get a tapestry of female voices, all rebelling against societal prejudices and expectations, while encompassing the different waves of feminism at the same time. Virginia Woolf’s words pave a path, Laura lives a claustrophobic life, and Clarissa finds that there is still work to be done.

The Hours dives into so many other civilization-based issues, including the AIDS crisis, the repercussions of World War II, and et cetera. Even though I know Daldry’s track record, he doesn’t get too carried away here, even with all of these moving parts. If anything, I feel like The Hours is the picture he’s been trying to capture again all of these years. It’s the understanding of time being used effectively by individuals, wasted by old fashioned politics getting in the way of growth, and shared by loved ones who don’t know how much time they have left. Every tale deals with death, personal suffering, and the ambition to move forwards. It is always aware of what it needs to convey, and it hits its mark every time. Nineteen years later, I’d even consider The Hours underrated and not discussed enough. It’s an awards season juggernaut that actually sticks its landing, enough to age gracefully with time.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.