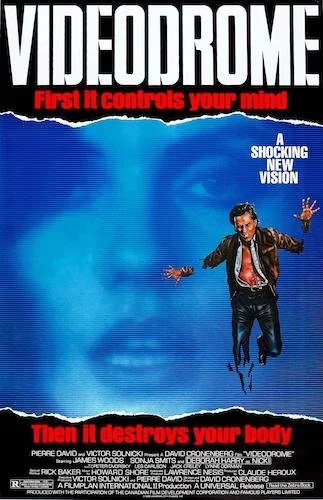

Videodrome

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

We’re reviewing one horror film per day for Halloween! Request a film to be reviewed here.

There are three different films that placed David Cronenberg on various maps. Scanners was his first hit of any sort, and it solidified him as the next voice of horror independent films (as well as a Canadian presence here). There’s also The Fly which was Cronenberg’s most mainstream proclamation to the world while he was on the rise (he naturally reverted back to Canadian weird-house, body horror films swiftly afterward with Dead Ringers). In between these two works is Videodrome, which — to me — is the introduction to Cronenberg as we would forever know him. Of course, he was always making his absurd works even well before this project, but he was finally given a budget he could really work with, and it was as if even this stepping stone was enough of a blessing for the auteur to go hog wild. Scanners is the kind of film that genre fans or Cronenberg aficionados will dig. Videodrome is a straight-up fantastic film.

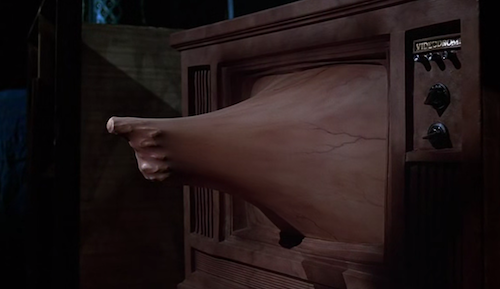

The term “body horror” is synonymous with Cronenberg now, and Videodrome feels like one of the finest examples of this label, especially since we’re seeing the human body not even acting naturally in any capacity; at least The Fly is a body betraying itself after an experiment gone wrong, Crash is the destruction of the human body as a dangerously fetishized object, and Dead Ringers has the human anatomy used as a complex machine at the mercy of the warped mind. Videodrome becomes nearly indescribable at times, including one’s abdomen turning into a functioning cavity that can conceal things, a hand transmogrifying into a permanent weapon, and so much more; all in the faces of capitalist corruption, over-sexualization, and the deconstruction of humanity as fodder for the machine.

Videodrome is constantly uneasy to watch, and it’s oh-so great.

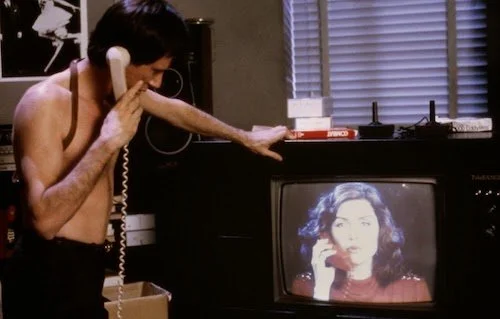

We start things off with Max (played by James Woods in his prime): a TV station president who is fixated on fabricating the truth. He would quickly discover a world unbeknownst to almost everyone else, which is an ironic twist of fate (reality was far stranger than any untruth he and his employees could sensationalize). This is an underworld of sex, danger, and rejection. The pains and pleasures of sadomasochism are only the beginning, as Max discovers a reality where lives are expendable; this goes beyond a fantasy at this point. What transpires is the repulsion of one’s own anatomical vessel in the name of sacrificing against the humanity that we have become; “all hail the new flesh”.

Cronenberg goes beyond a basic premise here, especially when he begins merging his insane imagery with greater themes of society; the bulging television face is just the beginning. It’s the kind of growth that proved that Cronenberg was destined for greater things; no longer could his scares be directly linked to obvious metaphors. Now you were a part of Cronenberg’s world, and it was an unforgiving one. You would either leave disgusted or absolutely transfixed. I’m of the latter demographic, who is continually blown away by the Canadian icon. Videodrome, for instance, gets so crazy with its deformations of the human body that it’s almost impossible to wrap my head around what exactly it all means. When we end on Max’s final words and his evolved hand, there’s absolutely no use in trying to figure out where these ideas come from. I surrender to Cronenberg’s creations more than most horror directors with similar ambitions, because he has this knack to somehow have these inexplicable designs feel believable (despite how absolutely unbelievable they are, really).

David Cronenberg is a director who can make even the most absurd images somehow ring true.

Would Cronenberg get weirder? Yes: enter Naked Lunch. Would he get more bold? Absolutely: Crash is one of the most daring and uncompromisied films of the ‘90s. Could Cronenberg get better? I think so, with his opus The Fly just around the corner. However, this steady consistency of David Cronenberg and his singular style of horror starts with Videodrome: his most well-assembled and mystifying film at that point. It’s proof that inventive minds really do take off when provided the chance (in this case, all Cronenberg needed was a decent budget). This was far from the end (as history has told us), but even looking at Videodrome outside of his filmography in a linear sense allows us to see yet another brilliant entry in his unforgettable lineup. He has done more — oh so much more — but Videodrome is important for this filmmaker to have found his footing the right way, and it was an instant leap in quality; this proved that he had arrived exactly where he needed to be.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.