Freaks

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

We’re reviewing one horror film per day for Halloween! Request a film to be reviewed here.

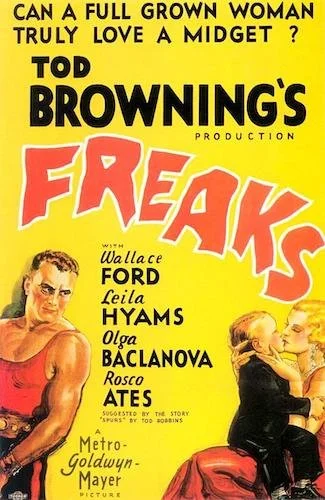

Warning: the following review discusses various disabilities and disorders in a film shown through a horror genre lens, and there may be triggering elements brought up, including in the official film poster shown below. Reader discretion is advised.

I don’t think Tod Browning’s final hurrah Freaks will never not be controversial. The disturbing truth is that the film was initially written off because it featured numerous performers with disabilities, but not for the reasons you’d be hoping for (perhaps a discussion on whether or not such a choice is the exploitation of people who society has treated unfairly for their entire lives). Instead, there were audiences that were upset that performers with these disabilities were being shown at all, as if they were repulsed by them. That breaks my heart more than you can ever know, and despite Browning’s affinity for shocking audiences (this is the same guy behind Dracula and The Unknown, amongst other provocative films), I don’t feel like it was his intention to make persons with disabilities the tropes of horror here; rather, I feel like their growing resentment of being used (which cultivates as collective hysteria and madness), as well as their abuse, is more of the angle he was going for. I can’t say for sure, but that’s my read on Freaks. Then again, it’s tough to know how to feel when the official poster of the film is so derogatory towards little persons.

Now, Freaks remains controversial for different reasons: because of how tricky its subject matter is (case in point: I’ve already had to perform a dance to try and explain how I think Browning shot the film without complete certainty). Is Freaks problematic with its approach to storytelling, or is it actually trying to show remorse to circus performers that have been abused by society for many years? Again, I can’t say for sure, but my high rating and appreciation for the film is through the understanding that Freaks shows tenderness towards its performers (even if through a dated lens that itself is far from perfect), and that it is the personalities of people that dictates whether they are beautiful or ugly. This film came out a couple of years after film entered the era of the talking picture, and cinema itself was once attributed to sideshows, circuses, and other areas beneath the elite. As one of Browning’s sole sound films, Freaks acts like a study on where this disgusting side of humanity comes from: the very side that finds amusement in the pain of others.

Freaks is, admittedly, incredibly difficult to write about.

In all honesty, Freaks remains so challenging to review, outside of knowing that it greatly affected me. It tore my heart up into many little pieces, especially seeing not just a film about how certain disabilities and disorders are treated, but a slice of life that was quite frankly contemporary back then (and even today; I couldn’t help but think of all of the shows I’ve forever despised like the Jerry Springer Show and Maury that exploit people). The karma I hoped for when it came to the characters that wanted to abuse and manipulate these performers became a driving force in the film: please let the evil people get what they deserve. It’s difficult to know what Browning was wanting to achieve with this story, especially since his career is kind of attached to the kinds of films that attract notoriety on purpose, but I know how I feel about this picture.

The film has been a pop culture staple ever since then, and is considered one of the most genuinely terrifying films ever made. I feel like the emotional connection to these maligned performers — including Harry and Daisy Earles, Simon Metz, Minnie Woolsey and more — is what grows such an investment (at least for me), so when the moments of unified hysteria happen, you are right in the middle of this picture. I feel more horrified by seeing what these actual people (entertainers, not by choice) were forced to do in their daily lives (and, thusly, here, as a reenactment of their lives). The iconic “one of us” sequence tells more of a mindset implemented by a hostile society that neglect a number of its citizens for the benefits of entertainment than turning these performers into villains or monsters of any sort. Again, this is just how I read the film, but I cannot fault anyone for feeling otherwise.

Again, I’m really having a hard time discussing Freaks.

I don’t know what more to say. Freak is easily one of the most effective films of all time, and it is virtually impossible to feel nothing whilst watching it. I can’t dive any more deeply than I have already, because Freaks, once again, is just so tricky to write about. It is a film made within the grey area of the moral compass, and how one reads the film most certainly will tell much about their character. All I can suggest is to watch the film for yourself, unless its subject matter will unquestionably upset you in any way that you can’t justify around. See how you feel about it. It’s an early example of a picture that truly challenges you to explore and discuss ideas you weren’t prepared for. Enough people suggested this film for me to review, so I feel like maybe you are all in a similar boat in trying to wrap your head around this one. I hope that I have helped in any way, but my inability to concretely narrow down the inexplicable response I got to a film as polarizing as Freaks likely may not be satisfactory, and so I apologize. What I can say is that it is occasionally nice to be unable to really pinpoint how art makes me feel, especially when it’s as visceral as Freaks is: an unhinged discussion that doesn’t hide behind anything.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.