The Power of the Dog

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Today is a special day for me. I love the works of Jane Campion, so I was naturally going to be excited for The Power of the Dog regardless. Then it made major waves at the Toronto International Film Festival as a heavy favourite to win the peoples’ choice award (it would come in third behind Kenneth Branagh’s winner Belfast). After her couple of Top of the Lake seasons, it’s time she returns to the big screen, and during a time when the pandemic’s measures are slowly being lifted. It is my pleasure to say that, yes, you must see The Power of the Dog on the big screen. It’s a Netflix release, but please don’t let that be a convenience for you. This is a picture that deserves as much as Dune to be seen in a theatre, and on the biggest screen possible. This is Campion’s triumphant return to film, and it brings a smile to my face that this is one of her greatest cinematic achievements.

Part of this success comes from how serene this picture is, when Campion usually operates with more oomph. To see the auteur legend have a film this minimalist, this sublime, this organic is quite something. See, for those of you who aren’t familiar with this master filmmaker, Jane Campion is one of the best directors of period piece films, particularly for her ability to use her historical and anthropological fascinations to help her inject as much factual realism into her works. Not once do you feel like her characters are performers wearing costumes, or that these settings were built for temporary usage. This has always been the case, so you aren’t going to be let down by how nicely The Power of the Dog transports you back to the early ‘20s. However, this feels like a bit of a different occasion for Campion, especially because of the passive nature of Dog, as if you can slowly digest the details on the screen, become engulfed in this world that took place nearly a century ago, and be surrounded by this heartbreaking story.

The Power of the Dog is one of Jane Campion’s most breathtaking achievements.

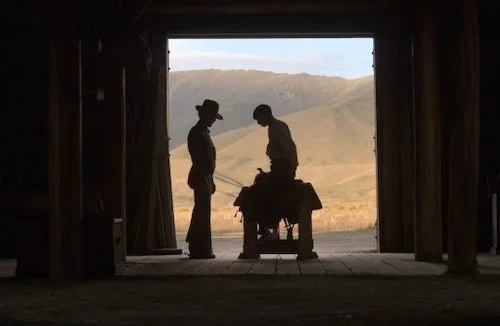

Somewhat atypical for Campion is how The Power of the Dog is paced: rather slowly. For me, this is a major win, since it feels like the kind of story that really begs to be lived in, so its speed actually feels quite right; it’s noticeably glacial, but it never feels like it is dragging, or that the film is longer than it needs to be. Of course, Campion and company are operating as modernly as possible. You have some jaw-dropping visuals from cinematographer Ari Wegner, with enough sepias, golds, creams, and beiges to remind me of Days of Heaven (which is always an honour to be compared to, I’d say). Jonny Greenwood has done it again this year (with his beautiful compositions in Spencer having just been released to the world), with a score that reminds me heavily of his iconic work in There Will Be Blood, particularly with how frantic and unforgiving his music can be (however, some of his most straightforward and beautiful work is here as well).

With all of this combined, you have a touching picture mostly made up of gorgeous artistry and the occasional devastation. The film is an adaptation of the novel of the same name by Thomas Savage, and it is full of a number of personal agendas tossed together to make a series of calamities (although it is subtle in this film, which prioritizes the spaces in between life’s highs and lows as opposed to the main moments that other directors would scrutinize). The gestation of romantic interests winds up becoming the fodder of resentment, either out of distrust, bigotry, or vengeance. Not much is explicitly said in this film, but it’s about reading faces, body language, and the quiet that haunts the characters that are lost within their own minds.

The Power of the Dog is built upon the spaces in between the typical focuses of most films.

All of the players here do a great job, but it is worth point out Benedict Cumberbatch whose Best Actor Oscars campaign is about to kick off. Considering the quietness of the film, it is his scornful gaze, his bellowing yell, and his natural changes-of-heart that are magnificent to watch. This is important in a film where both major storylines surround his rancher character Phil Burbank, whose brother George (Jesse Plemmons) falls in love with innkeeper Rose (Kirsten Dunst); her son Peter (Kodi Smit-McPhee) is teased for his awkward nature and his apparent homosexuality. The weight of anger that Phil feels with Rose transitions into his relationship and discovery of a new life with Peter: a reminder that rage isn’t always the answer. Ironically, it becomes Rose that retaliates with this development.

The Power of the Dog has much more narrative complexity than what would appear on its surface, particularly since you may be left in awe of what you are seeing and hearing aesthetically. Dive deeper, and you’ll find one of 2021’s most devastating films, especially because of its rawness; there’s hardly any melodrama here to cloud what you are meant to feel, or to force you with the overfeeding of a specific emotion. It almost feels like Jane Campion is working effortlessly here, and that is what makes this latest effort so special. Considering Campion has been making films for decades now, getting such a pivotal film in her canon this late into the game is something I won’t be taking for granted. This is one of her strongest efforts thus far, as well as a major highlight for this year: an overwhelming picture that may very well send shivers down your spine for its entire duration.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.