Mad Men: Perfect Reception

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This is an entry in our Perfect Reception series. Submit your favourite television series for review here!

You can make the argument that nearly anyone even associated with The Sopranos has gone on to make their own legacies. Even Perez Hilton had a small part in the third season and went on to become a massive name. Needless to say that one of the largest success stories to come outside of The Sopranos (in the way that these people became massive in their own right, not entirely linked to the series) has to be writer and producer Matthew Weiner, who was picked up by Sopranos head David Chase after he read the former’s screenplay for an unnamed pilot. Once The Sopranos wrapped up in glorious fashion, it was time for Weiner to see if his newfound stature would allow for his actual dream show could find a home. Chase saw something in his writing (enough to bring him into his HBO defining family), but most other companies — including HBO — didn’t agree.

It’s important to know that we’re in the later years of the 2000s at this point. Buying TV series boxsets was the norm. Downloading shows was common as well. Streaming was around the corner, so network television was still able to keep its head up (however, as we know now, the end of the years of network television having any major hold on the wider television consuming audiences would come). Not to say that companies could predict what could come and what major moves could affect them in the distant future, but Weiner’s creation’s home would be important. Could this have been a major push in HBO’s quest for complete domination? Would it have been the first big title to be the face of streaming? What about Showtime? NBC? ABC? The answer would end up being AMC in 2007, who would go on to release another major series one year later (a certain Breaking Bad).

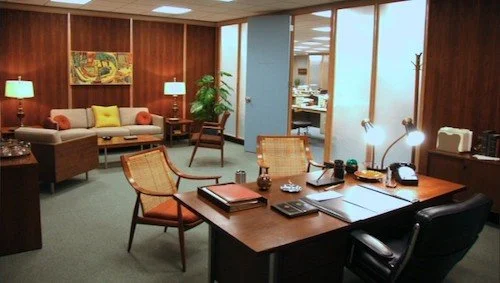

But first came Mad Men: Weiner’s vision from as early as 2000. It finally had a home, and it was thanks to the previous number of years with Chase and his legendary series that Weiner had this opportunity at all. It’s safe to say that he was going to make the most of it. The first aspect to note is just how different the premise was. When the bare basics of a series usually fell in a number of categories (medical practices, legal departments, police forces, you take your pick), we now were placed on Madison Avenue in New York, New York to see the lives of advertisement schemers during the rise of the idea of pop culture: the 1960s. We start right at the dawn of the decade, enough so that the last breath of the ‘50s can still be felt on the backs of our necks as it slowly fades away. This kind of fixation on the time period only begins with how it looks. One thing that Mad Men would become synonymous with is precision: just how meticulous Weiner and company could be with transporting us to a time of yesteryear.

When I say Mad Men was incredibly fixated on being accurate, I mean in every way. Akira Kurosawa's levels of making sure stuff that even the audience couldn’t see were still done right. Right down to the appropriate shapes and densities of ice cubes, Mad Men was as ‘60s as a show could get. However, types of curtains, what drinks came out when, and other visual pinpoints are only half the story. The actual timeline of the series lines up pretty much identically with real events, particularly with their actual timing as well. If you break down the entire series, seasons, or even just basic episodes, you can actually make the case that everything lines up. If characters watch the moon landing, spot the toxic fog of 1966 in New York City or any other major occurrence that we can cross reference, you can see that the hours before and after check out, and that no major plot or time holes are made. It’s scarily accurate, to the point that you can read up the news of each day and just imagine the Mad Men characters experiencing these affairs in their daily lives.

What mattered more than the little things is the story itself: the very one that made David Chase want to bring this writer from Becker named Matthew Weiner onto his Sopranos team. Six years after Mad Men concluded, it’s safe to say — even without recency bias — that the series was impeccably written, with nearly every plot thread, character, and idea concocted just right (and very little to complain about). Again, this series was already fresh with the concept of advertisers in the ‘60s, but it’s also what Weiner did with the characters within this universe that made it click. We think of the ‘60s and other older eras with rose-coloured glasses. I myself love the decade and find it to be my favourite cinematically and musically. However, I can acknowledge the massive amounts of concerns and problems of the era, and that’s the basis of Mad Men: noticing how far we have come.

Right off the bat, you can spot the team of straight white men that run the advertising agency Sterling Cooper, and the women and persons of colour around them that have to adjust just to get by. Seeing these characters not live in a fictional realm where everything is fine and society is kind to all was just the start. This granted opportunities for these characters to grow, and we were looking from the new: a lens of the internet age where we can fight for progressive change and spot the enormity of these social issues and not tiptoe around them. Mad Men walked the walk by actually proving to be a feminist show, especially with the hiring of female writers to better navigate these discussions; by season three, all but two of the nine head writers were women, For a show that looked back, Mad Men was quite ahead of the curve.

One significant example is the character of Peggy Olsen: one of my all-time favourite character evolutions in television history. Played perfectly by a never-better Elizabeth Moss, Olsen plays the outlier: the naive girl that shows up to Sterling Cooper on her first day in the premiere. All seems hopeless for Olsen right away, but any fan of the series knows that there is nothing to worry about. Olsen fights against the sexual gazes of her male coworkers (and the brunt end of misogynistic lacks-of-faith by the same men) to blossom into one of the show’s most powerful characters: a leader who won’t take nonsense from anyone. Even if the entire series was based on Olsen, the series would be so inspiring and riveting. She’s only one of the many characters who experience such a beautiful transition. Pete Campbell, the one-time playboy try-hard, becomes a better version of himself. Joan Harris turns from someone who adapted to society to someone who vows to pave the way. You can go through most of the characters this way.

Then there is the series lead Don Draper: one of television’s most interesting antiheroes. You fully understand why he is an advertising genius and how he can get everyone to pay close attention to his marketing, but you see the other side: the sex addict, alcoholic, selfish man who is tortured by the demons of his past. Played by a then-under-utilized Jon Hamm, Draper was suave and charming on the outside but a complete mess internally. If anything, he’s the one character who kept stymying himself time and time again. As others evolved around him, he kept digging his hole deeper and trying to claw his way back out. In a series where the timeline is ever so apparent, there’s something haunting about seeing the world evolve more quickly than a man that was cementing himself in place to avoid confrontation. Don Draper as a person was Don Draper’s greatest advertisement (well, for most of the series; his magnum opus would arrive towards the end).

Mad Men started off just like any other show, or so it felt. The first two episodes felt almost episodic with one goal: the securing of clients to make ads for. First was tobacco giants Lucky Strike. The second episode expanded the Sterling Cooper lore a little more. All of this changes quickly by episode three when Draper is revealed to be Dick Whitman: a survivor of the Korean War who assumed his identity from a fallen soldier, as the means of starting a new life to escape his troublesome past. This explains Draper’s inability to grow: he isn’t even his real self. Everything else speeds by him. Sterling Cooper becomes Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce (and would continue to change furthermore). Partners come and go. Loved ones and acquaintances would die. Don Draper would forever be Don Draper because he was an idea and not a person. It’s a heartbreaking stunting of one’s growth that I would feel worse about if Draper wasn’t such a problematic person. You’re not meant to love him; you can just understand him.

Fast forward through the entire series, and we get to the final season (seven), which was split in half. Part of the reason was that the first portion takes place in 1969. The rest zooms outside of the decade; we’re now in the ‘70s for — coincidentally — seven episodes, and it was time to see closure to both an era and to all of these storylines. Like I said earlier, every other major character was well-rounded and crafted like pieces of art; some of the strongest arcs in all of TV. Draper was still himself, and it was starting to get worrisome. By now, he was cast out from Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce (now Sterling Cooper & Partners) because of his downward spiral. He was now twice divorced because of his cheating ways, addictions, and anger issues. His bender only keeps getting worse and worse. I was convinced that Don Draper could only die at the end of Mad Men.

In a way, he does; the Don Draper that we know of, anyway. As other characters move on to better things, develop new paths, and grow even more, Draper exiles himself to cross the lands of America: the nation he fought for as a soldier, and the audience he sold a myriad of ideas to as an advertising giant. Now, he was one of its inhabitants, trying to just get by without self-destructing to the point of fatality. He winds up at a commune in the series finale, stripping himself of any materiality (the same man who devoted a major portion of his life to selling ideas to the United States, insisting that we all need what we don’t need). He is in a lotus position, with his eyes closed, and suddenly a bell rings and he softly smiles. We think he has found himself. He really found the greatest advertisement of all time. The last of the historical accuracies are put to the test with the showing of the 1971 advertisement known as the “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” campaign (obviously from Coca-Cola). This whole series led the strongest advertiser to make his greatest invention. Of course, some guy named Don Draper didn’t make this ad (Bill Backer did), but the agency (McCann Erickson) is the very one that Draper winds up at. What a slice of revisionist-yet-precise storytelling.

Mad Men was dominant when released, but its nurtured storytelling is cut from a different cloth than its bombastic characters. It’s as if Weiner took the David Simon approach of The Wire more than the David Chase way of The Sopranos: each episode didn’t have to stand alone as some sort of statement, and everything was a part of the greater whole. The one major Chase element was the vague final image, but instead of a disappearance into nothingness, it was the gentle easing-into one final advertisement. In hindsight, it makes sense: it took an entire lifetime (or, in the case of Don Draper, two) to make such a meaningful commercial. It’s this kind of poetry that makes Mad Men stand out. It was already destined to be one of the greatest network shows of all time. It’s the attention to detail, the mind-blowing developments, the rich aesthetic (every shot was gorgeous), the time capsule finessing, every single element of Mad Men was beyond just good; they were masterfully made. I’d like to point out that I usually highlight a few key episodes in my Perfect Reception series, but I find that hard to do with Mad Men, simply because it feels like one giant seamless adventure rather than something I feel comfortable breaking into parts; of course some episodes stand out more than others (“Shut the Door. Have a Seat” and “Waterloo” come to mind, amongst many others), but that’s beside the point. Mad Men is just such a fluid, cohesive experience, which is especially shocking for a series that went on for a whopping ninety two episodes (and not a single major misstep).

As a result, I feel like enough time has passed that I can make the argument that Mad Men is the greatest network show of all time, especially around the tail end of the network era; now it’s almost impossible to replace. It’s ironic, considering that we have never been as inundated with advertising as we are now; here was a show, on a platform that needed advertising, that suddenly made one of contemporary history’s most maligned creations the works of brilliance, in the same way that awful human beings, toxic behaviours, and the numerous disasters of an entire decade all part of an exquisite televised mosaic of purity and prestige (especially the ways that Mad Men showed the overcoming of adversity). For a show about advertising, not many shows are this authentic and pure. It took a lot for Mad Men to be made, so it wasn’t an effortless gestation, but what a nearly-flawless creation that will only age better with time (yes, even when pitted up against the streaming and subscription giants that loom over it). Of all of the series I adore, Mad Men feels like one of the most complete I’ve ever seen.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.