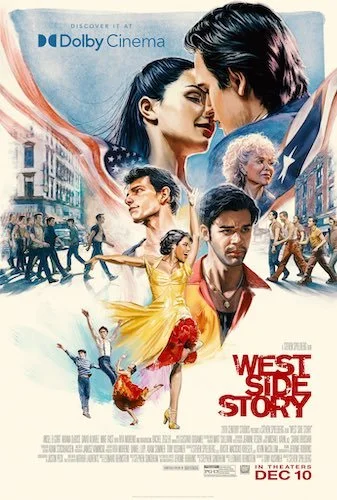

West Side Story (2021)

Written by Cameron Geiser

The opening shot of this remake is not of the New York City skyline as in the original, but instead, its inverse. Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story begins with a top-down view of what appears to be a war zone. Swooping low over the debris until the camera slows, rootless young men suddenly emerge from the ground, as if clambering out from a bomb shelter after a raid. These teenagers, as they are about to tell you, are the Jets. They’re just one of the many gangs of New York City, and they’re living in a time of transition. Apartments sit in mid-wreckage, piles of building supplies and discarded material lay at every corner. The grays and charcoals of the rubble from the ongoing gentrification of the neighborhood that will eventually house The Lincoln Center signals a time of inherent change. The desaturated color palette of these scenes clash with the vibrant, earthy, colors of the Puerto Rican neighborhood that the juvenile Jets strut into to display their arrogance and bravado. They steal signs, deface cultural murals, and generally try to intimidate the immigrant neighborhood’s denizens. That is until their rival gang, the Sharks, show up in similarly aggressive fashion to show off their own style of power and flare in equal barbs. This story is all about conflict after all. As was the case with its 1961 predecessor.

The West Side Story of 2021 captures the emotional and political rifts that haven’t quite gone away since the gestation of the original stage production, and even the 1961 film.

So, this is a remake right? What’s different? Was it worth it? What works and what doesn’t? I’m happy to say that almost everything in this version is a rousing success! Spielberg and company took the skeleton of the original and kept what mattered most while making appropriate changes and flourishes where needed. Nearly all of the principal characters have been altered to some degree, but with respect to the core attributes of who they are. Ansel Elgort’s Tony has spent a year in prison for a fight in a previous rumble, and he’s no longer interested in the loyalty of gangs. Though he has a hard time giving up old alliances, no matter the potential danger. Rachel Zegler’s Maria now has a rebellious spitfire spirit alongside her traditional innocence. Zegler’s got a spellbinding voice, and while she may be small, her singing could calm the frontlines of a war. Which is fitting given the circumstances of the characters surrounding her. Maria’s brother Bernardo, played by David Alvarez, is now a boxer. He’s also got a bit of an aloof rockstar attitude at times that shines through the bravado as well. Bernardo’s girlfriend Anita is played with a fierce passion by Ariana DeBose — she steals every scene she’s in and does Rita Moreno justice in the role. Speaking of Rita Moreno, she’s also got a role in this version as well. She plays Valentina, the widow of a soda bar owner who allows Tony to live and work there while he’s still under parole.

The casting of the iconic West Side Story characters in this remake is strategic, and each character succeeds as a result.

This version is a bit smarter overall, especially with the world building and the character alterations that humanize and make them more realized individuals as well. Here, both the Jets and the Sharks are depicted as victims of gentrification, furthering the tragic outcomes that will plague both gangs by the end of the film. The Sharks see and recognize the racism they face in everyday life in America, but they strive for upward mobility in the country known for its dreamlike potential- yet brutal realities. The Jets are also modified a bit- they’re now the sons of abandonment and delinquency. Or as Lieutenant Schrank (Corey Stoll) calls them after breaking up a fight early on in the film, “..the last of the can’t-make-it Caucasians”. The film perfectly balances the familiar with a fresh coat of paint and a few new tricks to spare. The choreography is a superb example of this. The mesmerizing movements embody the soul of Jerome Robbins’ classic work in the 1961 film while evolving to become its own blend of respectful homage and distinctive newness.

I also have to take the time to make note of the cinematography, which, as the kids say, absolutely rules. It’s fluid, sweeping, and just as potentially explosive as the characters caught in its lens. This version of the film fights dirtier than the first and it’s more authentic in a myriad of ways, but the choices made in moving the camera are damn near mystical in my opinion. There’s one shot during the sequence when Tony searches for Maria by singing her name wildly throughout the neighborhood in which he’s framed from above, standing within a puddle, with it’s ripples surrounding him in the frame. The shot feels almost cosmically beautiful; you know you’ve done something right when a character standing in a puddle at night can look this good.

The 2021 West Side Story boasts a number of technical achievements, including its powerful cinematography.

For his part, Spielberg’s guiding hand has not felt this energetic or inventive in decades. The blocking, framing, everything down to the very feel of the movie screams classic Spielberg at the helm. While the famed director has certainly made some good (and great) films in the past twenty years, I haven’t felt the magic since his work in the 1990’s, with the possible exception of Minority Report. This one has it, for me anyways. The only aspect I feel I can critique at all is that of Ansel Elgort’s Tony. Admittedly, there’s nothing wrong with his performance per se; it’s just that when you have him alongside Rachel Zegler, Ariana DeBose, David Alvarez, even Mike Faist’s Riff (the angsty hair-trigger leader of the Jets)- Elgort’s cinematic acting alongside their theatrical performances can be seen and felt as lesser. It’s not bad, he’s just working with extremely skilled individuals that outshine him. Alas, it’s but a nitpick for a film that I feel is nearly flawless.

Cameron Geiser is an avid consumer of films and books about filmmakers. He'll watch any film at least once, and can usually be spotted at the annual Traverse City Film Festival in Northern Michigan. He also writes about film over at www.spacecortezwrites.com.