Being the Ricardos

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

If there has been any confirmation from Molly’s Game and The Trial of the Chicago 7 of anything, it’s that Aaron Sorkin will forever be a fantastic writer, but he may be a so-so director. The electricity of his dialogue, the back-and-forth wit of his scene sequencing, and the gestation of his characters is done in a way that is his signature style every single time, and his voice is strong enough to resonate in the works of other auteurs. However, I also think that the finishing touches done by other directors with his screenplays are what makes these stories pop as much as possible. David Fincher provided a mechanical coldness to The Social Network that perfectly matched Sorkin’s quest to find warmth in a digital age (and amidst legal and social conflicts). Danny Boyle’s off-kilter eye made Sorkin’s flashbacks and anecdotes pop more than any film before or after Steve Jobs. Should I keep going?

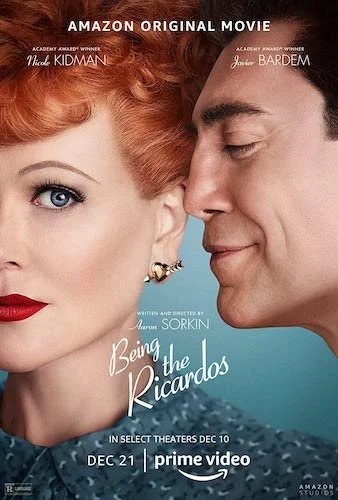

The latest evidence that Sorkin doesn’t know how to best accentuate his own writings is Being the Ricardos: perhaps his weakest film as a director thus far (although the screenplay is typically strong, as expected). The urgency to tell the rise of Lucille Ball and her behind-the-scenes prominence and struggles during I Love Lucy makes perfect sense. It’s 2021, and women are still being discredited and/or overlooked within film and television, especially when behind the camera. Seeing Ball and her then-husband Desi Arnaz experience their battles with showrunners and producers (particularly with how Ball could continue the show whilst pregnant, since incorporating such a topic was overly taboo for this time) is something that feels relevant even still, especially in regards to new audiences getting familiar with the real innovator behind the sitcom character. We have Nicole Kidman to thank for part of this success with her transformative performance, especially because she embodies both sides of Lucy: the mastermind visionary, and the comedic icon. Furthermore, Javier Bardmen (as Arnaz) and J.K. Simmons (as actor William Frawley) also steal their own scenes; the former with his charisma, and the latter through raw hilarity.

Nicole Kidman is sensational as Lucille Ball in Being the Ricardos.

These performances (and the solid acting amongst them) help make Being the Ricardos make a bit more sense than it could have otherwise, and they make Sorkin’s spicy dialogue land as nicely as ever. Otherwise, Being the Ricardos is uncharacteristically lopsided and — dare I say — glacial for a Sorkin film; his stories usually feel like all of the fat has been trimmed off, whereas Ricardos seems to trudge along at times. No amount of warm cinematography, dynamic editing, or memorable quips can get me to look past these narrative lulls, which seem to be the result of Sorkin seemingly playing ball with the usual biopic tropes. I can only imagine how much slower the film would feel without this help. These pauses are the result of Sorkin’s usual cutting between timelines, but his storytelling throughout Ball’s rise (and her growth of adoration for Arnaz) feels as by-the-numbers as his work has ever felt. Ball preached that TV series should treat their audiences with respect as if we can acknowledge them as intelligent beings. I don’t know if Being the Ricardos exudes the same philosophy if we are being spoonfed these moments.

Why do these flashbacks feel slower (for the most part)? Because of the imbalance here: some sequences shine as the visions that I think Sorkin foresaw and was aiming to put onto the big screen, whilst others feel much safer and less inspired. There are also depictions of documentary-style interviews with people that worked with Lucille Ball giving their takes on the goings-on during production (Ball being flagged as a communist, on-set stories, and more), which feel nice on their own, but they also don’t feel like they truly belong in the film (until everything comes together in the story’s purposeful final sequence, which I’ll leave you to enjoy). Despite all of this wonky filmmaking, Being the Ricardos still has just enough to be watchable. Again, Sorkin may not be my favourite filmmaker, but I’ll forever be in awe of his writing (at least to varying degrees). In the same way that his work shines through the films of other filmmakers, his writing strengths can even elevate his own directional flaws, with brilliant call-backs to earlier sequences, focuses on key issues in major conversations, and the business dialogue that only he can make feel like the most fascinating chatter on Earth. With a strong cast that shines through the mediocrity of Ricardos (they help Sorkin’s writing resonate more strongly in the same way that his writing helps their performances get better), you are guaranteed to at least feel bowled over by the human element of this latest feature.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.