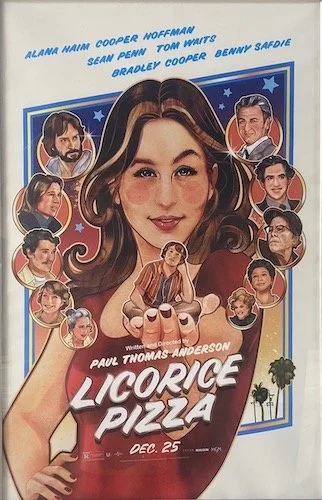

Licorice Pizza

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: may contain potential spoilers. Reader discretion is advised.

Without spoiling, there is a curiosity you may feel towards the end of Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film Licorice Pizza: a worry that everything you had seen up until that point — while highly vibrant with the pulse of life itself — may have been for nothing, and that this time capsule film is just an excursion from your own woes. It’s precisely when I began to feel this way that the film kicked into its main purpose: a sequence that wraps up each and every nostalgic vignette before it with a bow, only in the kind of way that the serendipity of life could provide. Up until this point, Licorice Pizza is a rare comedy-drama where virtually nothing feels predictable. I had virtually no idea what would happen at each turn of the film, and being dragged around on the ground as the film sprinted ahead was a part of the excitement I felt whilst watching. It was this conclusion that remained the sole moment I could acutely figure out, but I view that more as a win than a loss: this cauldron of emotions burst exactly the way I was hoping. This isn’t There Will Be Blood where I want that endless ambiguity, or The Master when the unanswerable dilemmas of character needed to be left not tackled. This is a genre diversion for Anderson: his lightest film to date. It’s the one time that he needed to play the exact card that this scenario called for, and he succeeds. The one time Paul Thomas Anderson — a typically singular auteur — played by the rules is the time Licorice Pizza slam dunks its exhilarating payoff.

Licorice Pizza is the most candid Anderson has ever been as a filmmaker, as he details so many aspects of his life in a number of flourishes. Having studied under a certain Donna Haim while in school, Anderson would grow up knowing the now-famous Haim girls throughout the majority of their lives (hence why he shot their videos). Alana Haim would star here, but her entire family — including mama Haim — show up as her on-screen household as well. Michael Penn made music for Anderson’s first two films, and so his brother Sean shows up here. Anderson’s longtime partner Maya Rudolph has a small part here, and so do their children. This level of personal intricacy and meta-purpose keeps going. Leonardo DiCaprio was meant to have a small part, hence why his father — writer George DiCaprio — pops up. The younger DiCaprio was replaced by Bradley Cooper, who maybe feels more fitting playing Jon Peters (producer of the ‘76 A Star is Born (this connection feels obvious).

Licorice Pizza is as personal as Paul Thomas Anderson has ever been, and it’s a side of his I’d love to see more often.

Then, there is the final — and most blatant — connection with Cooper Hoffman. His father is the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman, whose career blossomed alongside Anderson’s in the latter’s earliest films Hard Eight, Boogie Nights, Magnolia, and Punch Drunk Love. Their final collaboration was The Master, and Hoffman’s notable performance is one I will forever be angry about, knowing that he was robbed of a second Academy Award. Like many, I miss Philip all of the time. There couldn’t have been a more fitting young lead in this film than his son Cooper; I feel like he would have been here nonetheless, given that Anderson was channeling so many loved ones and their families here (other members of the Hoffman family have small parts here as well). It feels even more fitting to have Cooper here now, but I find it so difficult to watch him. I’ll get into Cooper’s acting In more detail later, but — and I rarely say this — he has been passed down his father’s talents almost completely. I saw Philip in every single frame, both in resemblance and in humanity. I wanted to tear up periodically whilst watching. Cooper is just as organically magnetic. His father would be so proud of him.

All of these connections boil down to a film Anderson made while struggling with another project (naturally, we know nothing about it, because even the films of his we do know are being made usually just pop up with little promotional awareness until weeks before his works are released). This was his means of unwinding a little bit: figuring his artistic self out whilst exploring his own self. He was inspired by American Graffiti: a capturing of all of the sounds and sights that surrounded him when he was young. While we do get this angle, I feel like we have a few other perspectives that shine here as well. This almost feels like his Roma (without being nearly as heavy-hitting and dramatic, of course), if you tossed in a little bit of Richard Linklater’s blissfulness here. With all of these ingredients comes a collection of random events and circumstances, but Anderson solders them together so effortlessly that you feel like you are staring life itself in the face (particularly life of the ‘70s). What’s fascinating about this goal is that Anderson is clearly nostalgic for a California of yesteryear, but he's also not stupidly blinded by yearning. He includes a lot of the hideousness as well, including the sexist overtones of various industries, the selfishness of juvenile behaviours, and a sprinkling of cringe-inducing racism (a moment which hasn’t sat well with everyone, and I can’t blame those that feel this way). Nonetheless, Anderson is representing life as he saw it, both the bitter and the sweet, even if they don’t always blend nicely together (like, say, a licorice pizza); it’s this dichotomy that makes the film feel multifaceted.

Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film embraces all parts of what he saw as a child: the beautiful, and the hideous.

On that note, that isn’t why the film is called Licorice Pizza (and nothing within this feature will explain it, either). Anderson grew up with the record store of the same name. It’s as simple as that. I’d like to think the fantastic song selection here had something to do with the title, though, as if Anderson could reflect on his memories with this playlist of his youth. In the kind of way that Once Upon a Time in Hollywood evokes, Licorice Pizza feels like you are living within this time period, and you can get lost within all of its aesthetic details. Even if you aren’t sure where the film is heading, it doesn’t matter when the film itself feels so effortlessly free of restraints. You are never entirely sure if you are watching a funny moment or an explicitly dramatic one, and the dramedy label feels like the best way to try and encapsulate this film (there are a number of examples of this throughout film history and Licorice Pizza isn’t the only work to hold this identity, mind you). Having said that, we still have Anderson’s funniest film (especially considering the bubbly tone of the picture overall, whereas the comedic moments in his other works may be amidst more serious sequences). The humour feels infectious for the most part like you are amongst friends that are shooting the breeze and kicking back to forget your responsibilities.

So, what is this life that we are neglecting for these two hours (outside of our own, of course)? We have two younger characters whose brief stories we experience. Alana Kane (Alana Haim) is stuck in a rut as an ignored member of society, who starts the film off as a lowly-paid employee that goes up to students on picture day to ask if they need a mirror to fix themselves up. She bumps into Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman): a child actor who has the confidence (and finances) necessary to get by (not quite a hell of a lot, but more than enough). Valentine is a teenager, given that he is in line for picture day. Kane is in her mid-twenties. It is already established that this is not going to happen, but Valentine sticks to the ideologies of his namesake and pursues the love of Kane. She shoots him down immediately, but entertains him platonically, as she is lonely. She is older, yet she lives at home, is going nowhere in her life, and dreams of a better life in a nicer world. Valentine may be young, but he’s already (seemingly) figuring it all out with his acting career and individuality. Their friendship allows them to turn the tables: Valentine develops jealously surrounding Kane and her own personal developments, whilst Kane learns how to push herself and find her enthusiasm and charm (and, as a result, becomes more likeable and noticeable). Of course, Licorice Pizza defies expectations often, and both characters end up contradicting themselves as often as they return to one another. You won’t have them figured out, because they don’t have themselves figured out, either.

Cooper Hoffman and Alana Haim deliver two of the best performances of the year, and this fact isn’t even up for debate.

Even though they are up against some major acting veterans, Haim and Hoffman end up being — easily — the two strongest thespians in Licorice Pizza, and I will guarantee that you will be blown away by them. There are non-performers throughout history that do a great job in an Italian neorealist way, but this isn’t such a case. No. Alana Haim and Cooper Hoffman are natural performers that have just been discovered at the same time. They deserve to be in many more films. Alana is sharp, dynamic, explosive, and yet she feels so purely so at the same time, and not once does she overact. You feel her anguish during her plights, as well as her softer side. If Alana Haim isn’t nominated for an Academy Award this year (yes, even with the tough competition around her), I will be furious. Then, there’s Cooper Hoffman, who has a more fun and grounded performance; his natural curiosity and allure are beyond fascinating, and not as easily replicable as he may lead you to believe. I don’t have a feeling he will be nominated, given the competition he’s up against, but I’d love a surprise nomination for Cooper Hoffman, here; he deserves it just as much as Haim does.

They are plopped in the core of ‘70s California, and all of its beauty (and warts): gas crises, exploding fads and waves, political campaigns, and so much more. They are trying to discover themselves and what life’s all about at the same time, and we’re right there with them, assessing what Licorice Pizza’s identity is. We partake in some exhilarating sights, most of them having nothing to do with the last: a motorcycle stunt for the hell of it, a horrific arrest, a Hollywood mogul’s psychotic episode, the launching of numerous entrepreneurial businesses, and so much more. Kane and Valentine experience all of these, either together, or separately whilst living vicariously through each other (and not even realizing it) in a nearly cosmic way. Kane falls in love a handful of times (Valentine a couple, as well), and I’m singling out this personal trait because there is forever a romantic angle throughout Licorice Pizza (whether Kane likes to indulge in Valentine’s discovery or not). It’s through one final episode of life (or at least of the ones that last within Licorice Pizza’s duration) that she learns something about men, and I’ll quote what she hears: “They’re all shits, aren’t they?”. Yes. Yes they are. In fact, everyone can be, and that’s one of the major realizations of life: everyone can suck, but you realize that the few people that don’t suck are the ones that make life so much better. It’s at this moment that Licorice Pizza all comes together in breathtaking fashion, and an already free-feeling film ends up becoming all the more elating.

Licorice Pizza is as blissful as any film in 2021 can get.

All in all, Licorice Pizza isn’t as good as you may hope it would be. No. It’s better. So much better. If Paul Thomas Anderson’s filmography wasn’t as pristine as it is, it would be easier to call it one of his best. I’ll phrase it like this: it’s amongst his best (especially given he has how many films that I adore?). I’ll also declare this. As perfect as There Will Be Blood and The Master are, or as fascinating as Boogie Nights and Magnolia are, or how much of an extension of his signature style as Phantom Thread and Punch Drunk Love may be, it’s nice to see a film like Licorice Pizza thrive. We don’t see Anderson stray away from his neo-Altman or neo-Kubrick styles too often. There’s Inherent Vice, which is being reassessed as a misunderstood film, but I can still safely call it one of his weaker films (only because, again, look at his career); it is an interesting stoner comedy turned neo-noir that allows you to get as lost as possible (through confusion). Again, it doesn’t work quite as well as his other films, but it’s also difficult to compete with his finest works. Well, Licorice Pizza does, and it’s his lightest affair. I won’t pretend it’s his greatest film (you can check out my ranking of every Paul Thomas Anderson film in my Wall of Directors), but Licorice Pizza affirms what we already know: he’s one of the greatest filmmakers in American history. To see him deviate this much from his typical tone — whilst maintaining his authourial voice — solidifies his ability to know how to nail every assignment. This is to him what 3 Women is to Altman, what The Straight Story is to Lynch, or what Lover’s Rock is to McQueen: a masterful outlier film within their canons. Anderson was already an all-time great. Here is further proof to know this (whilst getting to rediscover his greatness in a whole new way).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.