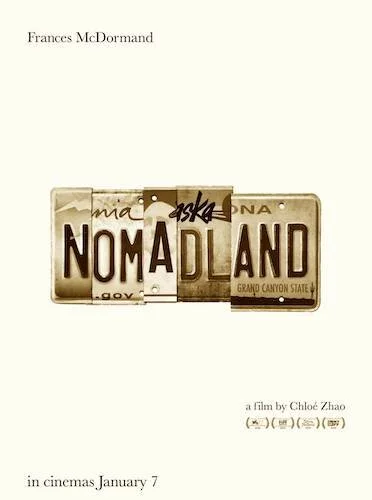

Nomadland

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Best Picture Project: a review of every single Academy Award winner for the Best Picture category. Nomadland is the ninety third Best Picture winner at the 2020 Academy Awards.

As vaccinations are given and the world is starting to feel a little bit like it once was, we are in the wake of a new America; the aftermath of a contemporary crisis in history. As far as humanity goes, there is a lot to spot: closed up businesses that haven’t been replaced; abandoned garbage, masks, and even vehicles marking the footprints of those that weathered this time; a floating apathy that is slowly being punctured by the light at the end of the tunnel. America itself has experienced a major shift, with arguably the biggest election in recent memory (results took around a week to finally finalize, and even the wait for this reveal of who would be president was heated and corrosive). Even before the pandemic, there has been an economic struggle, and some industries, neighbourhoods, and citizens were better taken care of than others; the tables are continuously flipped for some communities, and aren’t even open to other communities, who are permanently being neglected.

Despite the difficulties of these times (and those that preceded our present), it takes an absolute artist to find the beauty and poetry within all of this anguish, and that’s exactly what Chloé Zhao — one of the finest American filmmakers of the twenty first century (emphasis on the word “American”, given how much exposure of these sides of the United States she provides) — achieves with her magnum opus Nomadland. When I first reviewed the film (a few weeks after I had watched it), I stated that “I knew it was a picture I had to watch again and relive over and over”. I’ve done just that since, with my latest viewing of the film a few days ago. The first time I watched Nomadland, I was experiencing a beautiful tapestry of this hidden life of many Americans who have had to adjust. On this umpteenth watch, I have grown to adore all of the juxtapositions and complementary crosscuts (the talk of a ring being circular to resemble life, with a can being cut open right afterwards, or an alligator being fed meat being followed by a barbecue scene), the snippets of entire days or weeks captured in seconds, or even the miraculous call backs that you can blink and miss, or not even fully digest right away (the egg shell for Swankie lasts only a few seconds, but it carries a lifetime of meaning).

Nomadland takes a difficult reality for many, and shows the beauty within these adjustments of living.

This is all on Chloé Zhao, who adapted Jessica Bruder’s literary analysis of nomads, produced this humble feature, directed the entire project, and edited the countless hours of footage to make the end result. We get a living photo album or scrapbook, which makes the film feel almost contradictory in such a singular way; the film itself is minimalist and passive in pacing, but the plot speeds past you with bits of information that are delivered and received in mere seconds. The film doesn’t even reach an hour and fifty minutes, yet you get an epic’s worth of content (without the film feeling stuffed to the brim). Zhao isn’t even a fine filmmaker at this point. It takes an absolute master to make Nomadland: someone who knows how cinema functions to the point of its barest basics. Her signature style begs to be revisited time and time again. On first watch, Nomadland is clearly a well made picture. On the next viewings and beyond, it is clear that Zhao has made her own language; part Terrence Malick, part Richard Linklater, part Claire Denis; completely Chloé.

We follow Fern well after the results of the 2008 recession; by 2011, the ripple effects are beyond repair. We can identify with many of these struggles in 2021; we’ve barely even recovered from the previous hiccup. Zhao finds the communities that have had to reconfigure their lives to keep going (and she doesn’t place any political lenses or blame at all here; Nomadland isn’t about accusations or resentment). If anything, Zhao lets real nomads tell their stories, which leads to some of the more heartbreaking moments of the film; Swankie discussing her terminal cancer (which is actually the relaying of what happened to her husband), the suicide of Bob Wells’ son, and other devastating confessions. At times, Nomadland feels like a documentary, but I liken her approach more to what was happening with neorealism cinema in Italy back in the ‘40s, where non-performers were cast to provide their voices. Zhao fuses her version of the American tale of the new millennium with those who have actually lived it, and it’s a gut-wrenching marriage.

The fusion of real testimonies and the fictional tale makes Nomadland a relevant, empathetic feature.

Zhao uses lead character Fern as a means of observing the two different ideas of how one can live the American dream. Fern was punished for trying to live by the typical rules within the United States, and lost everything; the typical American dream is the pursuance of a marriage, a nice house, and kids to continue one’s legacy. Nomadland offers the idea of a different kind of American dream, and it’s one that Zhao favours: the appreciation of this great nation, its natural miracles, and the many travellers that wake up with brand new lives wherever they find themselves. It’s an existential kind of living, where the ways of society have no business affecting how people spend their days. Objects are mementos meant to be shared, or items used to help others, not capitalist means of hoarding and accumulation.

No matter what Nomadland is trying to say, it says it with complete love; even the more intense moments here are painted with a stunning glow, so you’re not shocked per se, but you’ll feel emotional in your core. Nothing about Nomadland is meant to be specific or direct. Even the final moments — full of implications of a never ending story, and the eventual reconnections with anyone anywhere — aren’t promises, but wishes instead. The truth is that none of us can dictate what will happen to us, whether we’re nomads traversing a nation, or accepting citizens of the system that “guarantees” us a living. All we can do is see each other “down the road”; whether on this crazy track known as life, or in the afterlife (even if only figuratively). In a political climate where we’re still feeling the heat of the last recession, the unforgiving kick of this current recession, the last dregs of the last elections, the suffocation of current political lies, the climate of the world change, and the shocking pandemic that has just worsened everything, we needed something relatable but not depressing.

Nomadland is exactly what we all could use: the warmest depiction of what most of us are going through, to varying degrees. Chloé Zhao’s gorgeous masterpiece is as thorough as it is simple, as deep as it is impressionable, as permanent as it is fleeting. Usually, the Academy doesn’t favour films this artistic or subtle, but Nomadland is special in both its urgency to tend to our wounds, and in its wide appeal (no matter what tone Zhao takes on). It’s an unbelievable effort that can speak to all of us at any time; even when we get out of these economic and societal nightmares (fingers crossed), we will likely carry these times with us forever, and Nomadland can be there for us whenever it is needed. It’s rare for a film to be this understanding of whomever may be watching it, but Nomadland is an open letter to all, whether you’re an American going through these events or any other person from around the world just wondering about life at all. As it stands, Nomadland is purely — but not exclusively — of the United States; all that means, to me, is that Chloé Zhao made the next great American tale, that will withstand the test of time.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.