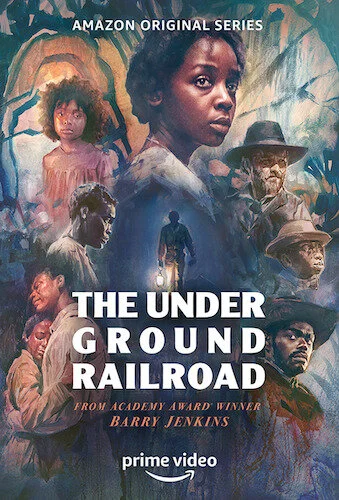

The Underground Railroad: Binge, Fringe, or Singe?

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Binge, Fringe, or Singe? is our television series that will cover the latest seasons, miniseries, and more. Binge is our recommendation to marathon the reviewed season. Fringe means it won’t be everyone’s favourite show, but is worth a try (maybe there are issues with it). Singe means to avoid the reviewed series at all costs.

Barry Jenkins’ artistic domination of the American film industry is impossible to ignore, every since his second film Moonlight became one of the finest films of the decade. It was part Wong Kar-wai, part Charles Burnett, but entirely a brand new, fascinating vision from a filmmaker we just had to know more about. As much as I love If Beale Street Could Talk, and I do, it felt similar to Moonlight artistically, whilst a very fitting homage to the works of James Baldwin otherwise. I didn’t feel like he would be a one-trick pony or anything, but I was excited to see more. Where could Jenkins go with his singular voice and vision? Once he was on board with that eventual The Lion King prequel, it seemed like we may not have found out how far he really could sprint; having said this, there are still a number of works he is releasing before then.

One of those projects is The Underground Railroad, which may feel like another safe avenue, considering this is a miniseries, although the Amazon stamp doesn’t hurt (typically, these big studios let artists do whatever they feel like with these types of works). If anything, The Underground Railroad is Jenkins at his most unhinged. Last year, we had Steve McQueen — an otherwise intense auteur — working with some lighter works, particularly the sublime Lovers Rock. It’s as if both filmmakers swapped places, as Jenkins (with his own miniseries, no less) is grittier and more harrowing than ever. Even with all of the gore and death, Jenkins has the ability to frame anything with such a tangible sheen (like the digital grain is an actual texture) and the utmost grace. Even at its most disturbing, The Underground Railroad is made to look like some of the finest visual art of 2021.

The use of cinematic tropes, like slow motion and crane shots, makes The Underground Railroad one of the main events of 2021 television.

I bring up the artistic nature of Jenkins from the get-go, because — and this is likely going to be one of the more polarizing aspects of the miniseries — The Underground Railroad is heavily an experience, and not a history lesson. Much of it is fictional, since it is based on the novel of the same name by Colson Whitehead. For instance, the railroad is an actual, fully-functional track, rather than a string of safe houses (which were actually made in the 1800’s). Furthermore, the actual events depicted are meant to create a tale from the time period, rather than tell stories specifically of it. Jenkins’ version is mightily fragmented, as if time and place don’t matter entirely; in the way that history repeats itself and much work needs to be done, The Underground Railroad just exists as a series of loops, leaps, and snippets. Rather than being accurate, Jenkins’ miniseries is almost Lynchian, like the swirling realities and connections of time in Twin Peaks: The Return.

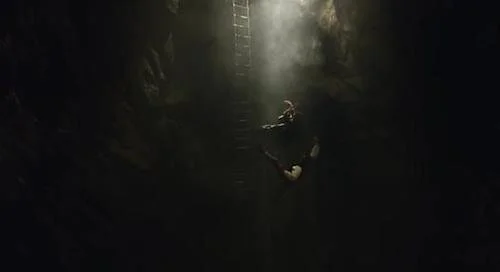

Within this borderline surreal manifestation is the mission of Cora and the loved ones around her (or connected to her). The series begins with images of free falling that are taken from the latter portion of Chapter 9, although it is framed less like a flash forward than one of the many memories sewn together in whichever ways Jenkins sees fit. We also hop perspectives, no matter what place in time they may be. This includes the lives and times of slave owners (and, perhaps, how they ended up as repulsive as they are), particularly Ridgeway (who specialized in catching escaped slaves). This also is shown in the shortest chapter titled “Fanny Briggs” (which is around an hour shorter than the longest episodes), and it feels like an anecdote placed right in the middle of other events. It’s as if Jenkins wanted to explore the confinements of episodic storytelling, and seeing what could constitute as a chapter, and how these portions relate to one another; these are episodes linked via juxtaposition.

The Underground Railroad is made more like a series of sensations and feelings than a story.

Within these broken rules are the closures of every single chapter: a contemporary song that reminded us of the resilience of African Americans, and their survival of systemic, enforced, and subliminal racism for centuries. Jenkins has always been extremely particular with the songs he picks, so Outkast’s “B.O.B. (Bombs Over Baghdad)” wrapping up the first chapter feels like a massive, invigorating flex. To prove his specific selection, what sounds like a remix of “Money Trees” by Kendrick Lamar is used in Chapter 6. For a more obvious approach, Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” concludes the ninth episode, and it is used on a lasting image that is meant to depict a clear picture of how the nation was founded. Otherwise, each episode is scored by usual Jenkins collaborator Nicholas Britell, with his usually painful-yet-exquisite orchestrations; as per usual, his compositions will surely linger with you.

What ties every song and concept together in this aesthetic whirlwind is the explorative cinematography that pushes The Underground Railroad beyond my expectations; I know a Barry Jenkins work is going to look nice, but the achievements here are ridiculous. They churn his ideas and makes them fully realized as masterworks. I’m talking about a landscape shot that floats into a birds-eye-view of Cora entering a lake in “Tennessee-Exodus”, or the overhead image of plantations burning (and seemingly chasing all of the fleeing people on foot) later on in the series. If Jenkins and company were going to create an experience rather than a historical event exactly as it was, then they had to go all out. They do just that, with countless breathtaking shots and conceptions. This also plays into the portions that Jenkins plans on you never forgetting, like the burning of a hanging, enslaved man, or the spillage of blood as it slides on the floorboards; even these are shot with Jenkins’ poetic vision.

Much of the series’ ambitions are devoted to how it performs as an experience.

There are other symbolic ideas, like a lunging snake creating the sound of a cracking whip. All of this boils down to The Underground Railroad’s primary function: to paint the monstrosities of racism from over time in one mosaic of anguish. The experiences that Cora endures are nauseating, but with the purpose of conveying the severities that millions of people faced. The railroad itself may seem a bit silly, but it is so enriching as a symbol of freedom and strength that perfectly matches the heightened figurative nature of the miniseries. Luckily, I wasn’t trying to expect any form of education of the time period, because I was glued to my television the entire time. Whether you’re expecting something factual or at least a little streamlined, you may be thrown in for a loop. Looking back at The Return, which was far more abrasive with its destruction of conventional television, I can’t help but feel a similar result here. Whether you end up liking it or not, The Underground Railroad feels like another major breakthrough in TV towards the always-extending tail end of its Golden Age. I can’t understand how any auteur wouldn’t want to make something as expressive, mesmerizing, haunting, and metaphysical as The Underground Railroad; whether they can pull it off or not is another story.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.