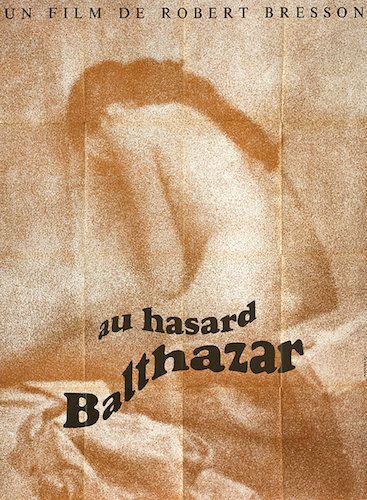

Au Hasard Balthazar: On-This-Day Thursday

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For May 25th, we are going to have a look at Au Hasard Balthazar.

When one discussed arthouse cinema, it’s nearly impossible to not think of someone like Robert Bresson, who presented his short, powerful films like they are statements more than anything. Even something like L’Argent ends so abruptly, as if it had said all that it needed to, and tied bows on top of these cinematic packages just didn’t matter. No. Bresson cared about getting right to the crux of the desolations of the human experience, whether it’s desperate people partaking in damning activities (Pickpocket), innocent civilians being abused (Mouchette), or tapestries of death (Lancelot du Lac). Some may point towards his 1966 film Au Hasard Balthazar as his magnum opus, and it can certainly make sense as to why: it manages to embody all three angles in large doses, as it depicts the putrid living conditions of the destitute regions of France (and the mistreatment of those already suffering within it).

Bresson loved using explicit images, and the two lead characters of Au Hasard Balthazar is as blatant as they come. A young girl (French star Anne Wiazemsky as Marie) and a donkey used for hard labour (the titular Balthazar). Taken straight from the works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky (particularly The Idiot), Au Hasard Balthazar is relatively direct as a screenplay, but each passage carries tons of grief and guilt. Even its opening moments are full of pain: Balthazar is accepted into a family farm (one which is placed right in the middle of poverty), and you know it is going to be worked to the bone right away; it is accepted with the promise of fortune by most, not by authentic love (outside of the children that try to take it in, and Marie who identifies with it immediately).

Th entire film has two sad tales operating simultaneously.

Both tales separate fairly quickly, but the horrors that plague Marie and Balthazar are what keep both tortured spirits connected throughout this hour and a half fable. What happens to both characters varies, and each martyr possesses a series of massive commentaries. Marie reflects the damnations of the lower class, the bleak futures of the new generation within a society of hardships, and the perverted, savage ways of chauvinism; the latter is darkly true, and is a topic Bresson has brought up a number of times (see Mouchette). In Balthazar’s case, there’s no symbol more aptly representative of the curses of labourers and the struggling workers of the world than a donkey that is burned out to the point of expiration.

As both spirits drift apart, they are still linked together, as if they are bonded by their traumas; it’s the only way they could get as far as they could. I feel like maybe Bresson was conjoining both characters as a means of alleviating the agonies that we endure on screen, but I personally find this to only make the hurt sting even more so. Think about it: we’re reminded constantly that they have been separated and are fighting these battles alone. I think this is almost sadistic, but our awareness of these ordeals is exactly what Bresson likely meant to happen; we are glued to the message of the destructions of innocence and faith.

Marie’s storyline is particularly graphic.

Ringing true to the unembellished stylings of Bresson, Au Hasard Balthazar does zero sugar coating with its developments; even its conclusion, as expected, is abrupt, shocking, and grim; it carries only a molecule of hope, only because we can’t say for sure what happens to all parties involved. Otherwise, Au Hasard Balthazar remains distressful throughout its entire runtime. Also akin to Bresson’s style are the very careful shots and cuts, almost primitive in nature, but an exercise in how knowledgable Bresson was of the cinematic language; he carefully played by the rules, but went about them in his own way. For instance, an obvious allegory is Balthazar being amongst sheep, with his dark hair standing out from the pack of bright wool; Balthazar is the noticeably abused, but the rest of the flock are the brainwashed that do nothing to help, and are taught to turn a blind eye, as to not face any dangers themselves.

You’ll find more symbols just like it, as Bresson believed in efficiency and maximized potentials of every image. It’s as if Bresson set out to wring out as much substance from each moment as possible, untainted by the common resolutions of movie magic (like growing orchestral swells, or dynamic close up shots meant to rub your nose in the emotions of a character). I can’t even call this poetic filmmaking, because Bresson operated purely with direct images and philosophies. There’s no mistaking what is laid out before you, and yet Bresson still possessed enough artistic flair to have each sequence and moment feel as poignant and nuanced as striking paintings you find in a gallery and never forget. There’s zero hyperbole, but Bresson’s powerful thumbprint remains.

Balthazar’s surroundings often tell a painful story.

Out of all of the works Bresson made (and there are a ton of classics; I’d consider Bresson one of the all time greats), Au Hasard Balthazar just sticks with any viewer perhaps stronger than anything else. At least Balthazar is a recognizable token, but it’s everything else Bresson accomplishes that allows the entire story to permanently affect you. All you can wonder is “what if?”. What if Marie went elsewhere? If Balthazar was never even found? Would they have lived happier lives? We’ll never know, but there’s also the possibility that they could have been punished even more. All we get is Au Hasard Balthazar, and it holds some of the most harrowing filmmaking techniques and results you may ever find. You don’t watch it to get sad. You watch it if you know what extreme sadness is. You watch it if you can empathize with its excruciations. If you can’t identify with Au Hasard Balthazar, then you are lucky. It will move anyone and everyone, but those who have fought against systems and unfairnesses, dealt with the worst behaviours of humanity, and strived to get through to happier times may watch the film once and forever acknowledge every second of it within their minds and hearts. If you haven’t seen it yet, it is worth viewing whenever you see fit. It is as perfect and brilliant as they all say. Just be cautious that you won’t leave the film the same as you enter it. No one does.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.