Is It Worth Reviving, Revisiting, Or Remaking Completed Or Cancelled Shows?

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

The Many Saints of Newark.

The footage is here. We can finally see some promotional material for The Many Saints of Newark: the prequel film of The Sopranos, starring the late James Gandolfini’s son Michael (naturally playing a younger version of Tony Soprano: the iconic role his father dominated television sets with). Sopranos creator David Chase is at least attached, so that is some good news. Besides, it looks like there is a little bit of sense put into this prequel’s story, not to mention The Sopranos’ fixation on Tony’s past and mental state, so this isn’t exactly strange territory to cross into. However, this is yet another example of a show that is being revived, revisited, or remade in some capacity. Perhaps The Many Saints of Newark looks a little more promising than some of these other examples that I will get into, but it’s still a part of this phenomenon that originally felt like some sort of a niche. A series like The Sopranos felt untouchable, and yet here we are.

What is this obsession with resorting back to classic series that have either been wrapped up nicely (like with The Sopranos, depending on who you ask, I suppose), or were cancelled prematurely? I feel like the latter makes more sense, since we all like resolutions, but sometimes we get to a point of no return. Freaks and Geeks feels impossible to follow up now, given how short the series is, how much time has passed (especially since it’s a high school dramedy that was made at the end of the ‘90s), and how busy all of the cast members are. There are answers in some other instances that work out okay, like how Serenity took a feature film to compliment the sole season of Firefly at least partially. Deadwood managed to revive itself over ten years later with the film of the same name. It’s clearly possible to help resolve shows that ended too early in some instances.

Otherwise, let’s go back to the question: what is the obsession behind these decisions? Let’s forget the need to finish stories, since we’ve gotten that out of the way, and it only answers one (revisitation) of the three Rs (the other two being revival and remake; I would classify reunion as a form of revisitation). Well, we know that many mediums (literature, cinema, video games, and even musical albums in some instances) have always had the sequel and/or prequel bug, which act as continuations of successful tales that audiences can identify with. They know the characters, the setting, and the general gist of what they should expect from any follow up. A storyteller and/or artist doesn’t need to test any waters for what audience they may attract: the crowd is already there. Networks, publishing houses, studios, developers, and many other companies would understand the dollars that could come in with these continuations, so it makes sense from a business standpoint as well; some sequels or prequels are busts, but you’d be foolish to expect that result right off the bat (unless the followup idea is absolutely diabolical).

Naturally, if these other narrative forms can allow continuations, it only makes sense that there would be this desire within television. If anything, I feel like TV calls more for this fixation. We spend countless hours — whether these are weeks and/or years of episodes spread apart, or consecutive binge watching marathons — with these stories, as if they are a part of our lives. These characters feel like old friends (even the worst villains). Settings are stomping grounds. Stories are memories. In this day and age, there’s an overall sensation that we all share anyway: nostalgia. Thanks to the internet, our connection with likeminded individuals, and other enabling factors, never has the world been so driven by nostalgia than it has been this new millennium. Narrative continuations are a scratch for this itch.

Twin Peaks: The Return.

We know the drive, now let’s look at the success rate. From my own perspective, most revivals or continuations of television series have not been worthwhile. I’ll never forget how excited I was that Arrested Development was coming back, since I considered it the funniest series I’ve ever seen (I still feel that way about the classic three seasons). What we got was a decent fourth season through Netflix, but an obviously flawed project where the chemistry of the original cast was now missing (since they could only get everyone in the same room a total of one time, and other interactions were similarly as strained). Still, Mitchell Hurwitz and company tried to replace the missing substance with a nice idea (the same event revisited from different perspectives Rashomon style). It worked, but only just barely. To this day, I still haven’t seen season 5 and don’t really feel like I want to.

The point is that the magic of the first series was gone, and we now had a perfect comedy tainted with a “just-satisfactory” fourth chapter (even with the best intentions and hardest of efforts to make this work). I can similarly think of a number of follow ups that just didn’t work out too well. Veronica Mars. Beavis and Butt-Head. That latest Animaniacs revival just didn’t cut it. Having said that, there are a few revisitations that have worked out just fine or actually quite well: Will & Grace was not too shabby, Mystery Science Theater 3000 was now being introduced to new audiences, and Doctor Who is, frankly, stronger in its revival than it was even in its heyday. At least we know that not every single attempt has been bad. However, outside of pleasing fans, has there been a need for these revivals? In each case — where context matters — you will find different answers.

The one time a continuation of a show (not a spinoff, but the continuation of a previous show that has ended) felt absolutely necessary and was a resounding success, in my opinion, was Twin Peaks: The Return. However, there are many things to consider. David Lynch’s lore was gargantuan by the time the show was cancelled. The series concluded on a massive cliff hanger. Even the prequel film series that Lynch tried to release got terminated after just one picture (Fire Walk With Me). Essentially, too much of Lynch’s insane, metaphysical vision was created, with too few answers provided, and borderline zero closure felt (outside of some storylines I won’t spoil here). Furthermore, Lynch demanded full control of this third season (a miniseries to be directed solely by him, with Mark Frost to help write every part as well); this almost resulted in a mass walk out of the majority of the cast and crew when Lynch threatened to quit the project, due to his budgetary requests not being met, and his ideas being questioned. It was the network meddling (ABC) that affected the second season of Twin Peaks in the first place. It was what Lynch, Frost, and everyone else was trying to rectify with The Return. There was a necessity for this third season for a multitude of reasons.

In that same breath, you can understand some additional instances of shows being revisited. Dexter was completely murdered (and not in a nice, clean way like the titular serial killer would make sure of) by the time it concluded, so a second chance — by the original show runner no less — to repair a legacy isn’t the worst idea (you can hear some thoughts about this on the Dexter deep dive episode by our friends over at TV Sessions). Believe it or not, I feel like remakes of bad works — while financially irresponsible and risky — are so much wiser than remakes of beloved classics, because this could be the opportunity to fix what went wrong in the first place. I absolutely despise anything post season four of Dexter, but welcome this opportunity, because I think it’s any storyteller’s right to make sure that a work concludes in a way they would want. Do I think it’s essential to fix Dexter? No, but more than enough people do that I feel like this is a must. This isn’t like the petitions to change Game of Thrones’ final season, either. The creator of Dexter isn’t happy. There’s no pandering here; just all of the disappointed being in agreement.

I haven’t really touched upon remakes until now for a specific reason. Remakes almost always follow series that have concluded and left their mark; as if there is this demand to introduce the story to new audiences (not by sharing the original form, but by doing it again, and usually not as well). Luckily, many classics haven’t really been touched (if they have, they were episodic tales that got resolved each episode, or anthology works like The Twilight Zone where subsequent attempts have borderline zero effect on the original runs). Even though I can’t find many remakes I care for in television, I find them relatively as harmless as the shows they are derived from. Is either Hawaii Five-O going to destroy societies? Outside of pay inequality and the poor handling of Grace Park and Daniel Dae Kim’s departures, I’d argue no. The series themselves are mindless entertainment (the original more fun, and the remake more intense). These might not be my cup of tea, but there’s barely anything to complain about, here.

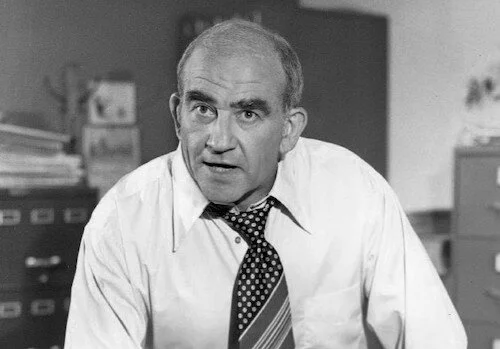

Lou Grant.

Since we’re back in the older days of television, I can observe that the concept of spinoffs was heavily prevalent back then. Hell, The Mary Tyler Moore Show had three of its own: one for Rhoda (which did well), one for Phyllis (which wasn’t quite as beloved), and even one for the cranky Lou Grant (which wasn’t even a sitcom like the original show, but rather a serious hour-long journalistic drama; I welcome the creativity). Otherwise, all of these other recent iterations (Fuller House, Saved by the Bell 2020, et cetera) are only following in the paths of what was done before them. Another notable example is a sterling example in fate being tempted. M*A*S*H, which I will cover in next month’s Perfect Reception series (thanks to your votes!), started off as a Robert Altman film, based on Richard Hooker’s novel MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors. The television series went on for eleven seasons, and kept reinventing itself as ratings shifted, cast members swapped, and competition stiffened. With a two hour incredible finale, the M*A*S*H series stuck its landing, Of course, it took a pointless spinoff in AfterMASH to prove that absolutely any series can overstay their welcome. How many versions of this brilliant story did it take to finally get stale? That’s kind of the point.

While it may always seem like a good idea on paper — to be reunited with familiar faces, places, and tales — some shows are meant to stay finished. The concept of a conclusion is ignored by American television networks, especially with episodic series. Something like The Simpsons can exist for over thirty years, with zero care that the series began to go downhill two thirds of a series ago. Everyone but Grey has come and gone in Grey’s Anatomy (okay, there are like two other characters that have been around the entire series, but you get my point). If you compare the two English speaking industries within television, British TV is much more concise, direct, and to the point (I’m ignoring reality shows and soap operas in this discussion). Compare the British Office’s fourteen episodes to the American variant’s two hundred or so (speaking of which, the American Office is a brilliant remake, even though it lasted for too long, and it is a rare example of such a concept being done right). In general, American wells are almost made to be dried when it comes to television. If we aren’t revisiting a series, it’s usually because the original series was so long to begin with.

Socrates stated — as detailed in Plato’s Apology — that death would be pleasant and peaceful if it were like a dreamless sleep. It has been considered a fallacy, since it is the act of waking up and feeling refreshed that wraps up a dreamless sleep. Staying permanently in such a state may not achieve the same desired effect that Socrates would have hoped for. It is resolution that helps determine whether or not a show is good. Had Homeland wrapped up after one season, or even at the end of its second chapter, it would most certainly be considered one of the greatest works of the 2010’s. However, it dipped, and it continued to sprint across the bottom of mediocrity. Deadwood was cancelled while it was still getting hot, and its televised conclusion may be less than adequate, but the series itself is beloved, given how great it was when it was still on the air. I don’t believe every single show or format demands to be concluded, since television series take on so many different intentions, but I definitely think that there is a problem when it comes to knowing when to draw the line with series. Something like Game of Thrones was different: the end was in sight, but it was butchered. I don’t think any prequel series can save that. However, even something like South Park — which has been doing astonishingly well for around sixteen seasons — can lose its lustre by lasting just a little too long.

Are there good episodes along the way? Sure. A bad season doesn’t have to be all bad. The point is that all good things must come to an end; let’s not refer to a still-overstated quote from The Dark Knight which will ring true here (to an extent), but there is some value in the recognition that too much of a good thing can turn stale (or, even worse, sour). I do think revisiting series (or remaking them) is the lesser of two evils compared to dragging them into the ground until they are barely breathing, especially when done well. Look at Frasier next to Cheers, or Better Call Saul next to Breaking Bad. There is no good instance of a show being exhausted (you either end when you’re meant to, or you last too long). Thanks to serialization, services like HBO, and other opportunities for creative liberties, not too many shows are tiring themselves out now. However, it brings us back to the other kind of exhaustion: bringing dead shows back. Sometimes, concluded shows should be left to rest. Not always, but sometimes. I feel like greedy corporations won’t care about crossing the demarcation that divides worthy examples and careless milking, but we have seen enough good examples that the idea of reviving, revisiting, or remaking series isn’t always the worst idea. It can result in some pointless television, but when the risk pays off, it’s either adequate or fantastic. Just like shows lasting too long, it would be nice if we could learn some temperance, though.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.