The Best 100 Documentaries of All Time

In the information age, the notion of watching a documentary seems fairly obvious; we as a species, concerned with societies and innovations, are always looking for ways to learn, advance, adapt, and be challenged. With streaming services breathing new life into the documentary medium, these kinds of films have experienced a reach unlike ever before. A good documentary serves its purpose: it educates viewers on a specific subject, and hopefully allows these conversations to keep going. The best documentaries never leave you, even if you've only seen them once, and I am happy to share one hundred of those with you in this list.

These one hundred films are exemplary cases of what documentaries can be, especially when these works break the rules, stretch their confining labels, or become meta forms of the genre. Before continuing, I want to emphasize the kinds of works you will find here. Straight up documentaries (including cinéma verité and direct cinema). Docufiction, where the real life footage outweighs the imaginative stuff. Concert films, especially if they have documentary footage in between moments. Film essays. Strange works that I felt like couldn’t quite fit in on my features lists (you will find two or three films below that really don’t fall underneath the guidelines of what common documentaries are, but they made more sense to include them here than as purely fictional features). To me, all of these types of films tell truths in their own ways. You will also find some works that have been proven to be disingenuous and/or containing staged moments; I’ll be sure to point out when those happen.

Otherwise, I find the following films to be the strongest works in the genre. I feel like documentaries have previously gotten a bad wrap, since the most bare-basics documentaries can feel a bit monotonous or of one specific nature. I can guarantee that documentaries are far more than just a simple type of film. If anything, I hope these one hundred films can enlighten you; documentary cinema can be limitless, but absolutely far less confined than how creative features are. Let’s get right to it. Here are the best one hundred documentaries of all time.

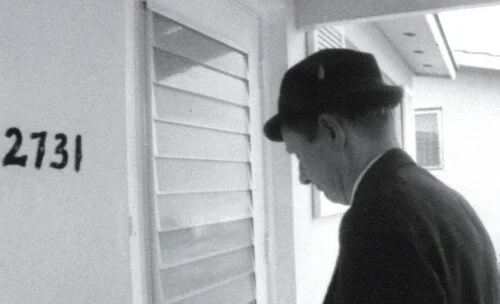

100. Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One

How do you capture the frustrations of a film set? Why, by faking a film set and documenting it, of course. William Greaves is an extreme provoker of truths and responses in Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, all in the effort of achieving a natural existence of a stale film set for the world to see. The mundane picture being made feels real to all except for Greaves himself, who keeps pursuing a false dream for others to follow. Greaves tends to push boundaries (including some ways that haven’t aged all too well; I’m thinking of certain words), but watch Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One knowing that this film was meant to cause patiences to boil over. This picture might be a rare pseudo-vérité: nothing is real, but it’s real for the subjects.

99. The Last Days of Left Eye

Music documentaries are bound to create personal attachments, and one of the more underrated pictures of this nature that I’ve ever seen is Lauren Lazin’s The Last Days of Left Eye. Following a trip to the Republic of Honduras for physical and spiritual cleansing, TLC rapper Lisa Lopes wanted to finally clear her name of all of the media-fuelled infamy surrounding her. What happened instead is a cursed representation of fates: Lopes promising that she feels a dark presence following her, leading up to the literal seconds before her tragic death. On one hand, The Last Days of Left Eye is a conventional music doc done really well. On the other, there’s no documentary at all like it (for better or for worse).

98. Bowling for Columbine

I have a few bones to pick with Michael Moore, but I can’t shake off how good Bowling for Columbine is. His opus — even after all of the controversy surrounding it has been discussed — is an effective take on the lack-of-control surrounding gun control. His stance is very clear, and he is unabashedly unapologetic with what he has to say (here’s my twenty-plus year warning which I’m sure is informative to no one). Nonetheless, Bowling for Columbine tries its best to figure out what exactly happened during the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School (it succeeds at great lengths). Do we blame the NRA? Marilyn Manson? South Park? Bowling for Columbine, regardless of Moore’s stance, reminds us that sometimes there just isn’t a clear person, creation or organization to point fingers at.

97. No Sex Last Night

Artists Sophie Calle and Greg Shephard used video cameras to document their road trip, in hopes of saving their relationship; either that, or they capture a severe breakup for the world to see. No Sex Last Night is both the title of the documentary, and the constant reminder that there is a distance between these two partners, no matter how good or bad their day has been. Leading up to an eventual sporadic marriage (after some difficult revelations), No Sex Last Night still is laced with bad news even when there are good progressions; is there anything more torturous than feeling as though a life commitment was a mistake seconds after it is made (or is it worse to break away from one that you love but are no longer in love with)?

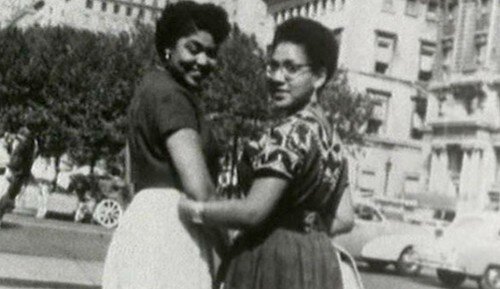

96. Before Stonewall: The Making of a Gay and Lesbian Community

You can thank the ghastly Stonewall by Roland Emmerich for bringing a much-needed urgency to revisit Greta Schiller and Robert Rosenberg’s vastly-greater documentary. Before Stonewall: The Making of a Gay and Lesbian Community was made roughly fifteen years after the actual Stonewall riots, but this picture is used to set the scene before the riots even took place; this is a depiction of a growing society that kept getting kicked into the ground. I guess you can call Before Stonewall the calm before the storm, but what an important message it gives: people don’t lash out for no reason. After an incredibly political 2020, something like Before Stonewall still feels essential to watch.

95. Amy

Amy Winehouse was due of a clearing of her name, and four years after her passing seemed like a good time (when the dust was settled, and people would listen). Asif Kapadia got rather risky with Amy, but it was all for the betterment of her legacy. Capturing the loved ones in her life that only drove her towards addictions, Amy is a statement that not everyone that is good to you is good for you. Kapadia also includes the punctuation moments of Winehouse herself realizing that she was not quite where she wanted to be mentally; her opportunity to record with Tony Bennett (her dream gig), only for her to beat herself up, is heartbreaking to watch. Amy is an important framing of mental illness and addiction battles, but it’s also a celebration of a blistering artist that we lost too soon.

94. Let There Be Light

John Huston’s films seem to be for the everyday American citizen, and this notion was carried over with his documentaries as well. Let There Be Light is a challenging picture meant to inform the public about post traumatic stress disorder attributed to World War II; it was sadly deemed unfit to show, and was hidden for almost forty years. Some of the best documentaries unveil difficult truths, and Let There Be Light is no different; censoring its existence and neglecting to educate the public is a disgusting — yet sadly common — decision. Now, we can see Huston’s words of caution. As saddening as Let There Be Light is, the film is shot with hope and love, as if Huston wanted to use his filmmaking capabilities to nurture the shell shocked.

93. Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills

Something about the trials of the West Memphis Three stuck out to directors Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky. Maybe it’s the extremity of the murders, or the mystery surrounding this small town in Arkansas. Perhaps they just wanted to defend their love of Metallica: the metal group attributed to these killings, acting as a direction of which to cast blame (Berlinger and Sinofsky would eventually document the band in Some Kind of Monster). Either way, Paradise Lost: Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills is an unbelievable count of all testimonies (from witnesses, loved ones of the dearly departed, and the accused). The non-biased stance of the film makes for some treacherous grey area: who do you side with, and why? Twenty five years later, it still feels nearly impossible to comfortably select only one side that Paradise Lost projects.

92. Burden of Dreams

I love Fitzcarraldo, despite the obvious hysteria of the film’s production. Of course, Les Blank was able to record at least some of this madness in Burden of Dreams, as he followed his director friend Werner Herzog all the way to Peru. The film-about-a-film begins with ambitious ideas: Herzog wants to lift a gigantic ship over a mountain like baron Carlos Fitzcarrald himself (these include replicas as well). As this goal turns into a never-ending nightmare (which has roped every cast and crew member in its snare), it’s clear that Herzog himself has actually become Fitzcarrald: driven by a vision, regardless of consequences. Burden of Dreams almost feels insane to watch, like this documentary shouldn’t be legal (which only makes the actual Fitzcarraldo film itself highly questionable from a moral standpoint).

91. Nanook of the North

Ah, yes. It couldn’t be a documentary list with Nanook of the North, right? In one way, Robert J. Flaherty’s picture greatly bothers me, with its obvious gaze (having many of the film’s events staged doesn’t help, either). On the other, I cannot help but admit the accomplishments of Nanook of the North, which range from how audacious this shoot was for 1922, and how it completely reconfigured the documentary medium. As much as Flaherty’s classic is questionable, it’s also daring (and actually well put together on a cinematic level). There’s no wonder why the film is shown in borderline every single Film 101 course that has ever existed; it hasn’t helped defuse the overrating of the picture, but the exposure of such a triumph never hurts.

90. Time

The latest documentary to truly change what the medium can be is Garrett Bradley’s bold plea Time. Robert Richardson has been used as an example and has been placed in jail for sixty years; his wife Fox Rich served for three and a half years, and has devoted the rest of her time out to try and clear her husband’s name. Time is partially dedicated towards shedding light on systemic racism, but its fluid nature — which blends current footage and home videos — is a reminder that time never stops. We revisit lifetimes as we are alerted about one that is confined; we’re constantly aware of how many seconds, hours, days, and years have been wasted, just so a man who made a mistake during a dire situation could be the poster person for others. The juxtaposition results in a painful-yet-sublime awakening.

89. Araya

Even though there is a historical purpose attached to Margot Benacerraf’s Araya, it almost plays out like a documentary that was made to frame natural beauty instead of get a point across. Araya is scenically gorgeous, and the entire picture exploits the four sides of a shot to make breathtaking snapshots of a Venezuelan peninsula. In black-and-white, the salt shines through the screen. Otherwise, Araya is meant to encapsulate the art of tradition that has been passed down, only for the picture to include a snippet of the “future”: the already-modern act of industrialism that has executed many ways of the old time and time again.

88. Inside Job

In one weird way, I don’t get as blown away by Inside Job anymore. I think that eleven years was enough time to digest just how disturbing Charles Ferguson’s revelations were. However, I don’t let that sort of acceptance persuade how I view a picture, because I will never forget that first viewing. We all knew there was something off about the financial crisis of 2008, but knowing that there was this much negligence, greed-driven manipulation, and clouding of the truth is enough to make anyone feel ill. The biggest problem is Inside Job is timeless: it depicts the failing economies throughout history (replace time specific variables, and it’s always the same story). In fact, I dread feeling like Inside Job is only going to feel extremely fresh in the near future.

87. Gates of Heaven

Before Errol Morris would get dynamic with his documentary filmmaking (see: The Thin Blue Line), his debut was a more humble, raw retelling of a side of America that deserved some love. I feel like the death of pets is something that gets shrugged off by those that never owned domesticated animals, but is empathized by previous and current pet parents. Gates of Heaven is for anyone: it connects the uninformed with a bit of insight with grieving animal lovers, whilst identifying with viewers that have been through this hardship before. There isn’t much of a point, outside of providing those with loved ones buried in a specific pet cemetery with a voice. It’s slightly strange at times, but Gates of Heaven is also wholly emotional.

86. The Five Obstructions

What film fanatic doesn't love coming up with hypothetical ideas (whether it’s dream films, or small ways a picture could have been improved)? Well, Lars von Trier went the extra mile with his cinematic fetishism in a way that most geeks could only dream: he forced Jørgen Leth to remake his iconic short The Perfect Human five times (with a set of rules for each stage). At first, The Perfect Human is now a little different, and you get the gist of the importance of decision making in film. By the end, you're left with a completely different picture that feels like it’s of another planet; you might even forget how we got here. The Five Obstructions is absolutely a film for film lovers. It’s an experiment that will change your perceptions of what cinema is on a fundamental level.

85. Man of Aran

Nanook of the North might have been the more iconic Robert J. Flaherty picture, given its influence on the documentary genre. However, I think Man of Aran has the former picture beat, given how more precise and fine tuned the picture is. Strangely enough, it’s an instance where the word “documentary” becomes very debatable, considering that Flaherty ran away with the staging of events and the retelling of facts; it’s hardly a real picture at all. In one challenging way, Man of Aran still works as a documentary in the loosest sense (like a few other titles on this list), because it is the capturing of life in a new way. Naturally, this couldn’t have been a Flaherty classic if there wasn’t some sort of polarization surrounding it, right?

84. Gimme Shelter

The trio of Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin were noteworthy for their verité expertise: they allowed life to just play out in front of them, and their pictures carried zero hidden agendas. That’s the best approach for a rock music documentary like Gimme Shelter, especially since it was released right at the height of the greatest era of The Rolling Stones. The performances are fine and dandy (the Stones themselves do much of the work), but it’s Gimme Shelter’s documentation of the notoriety surrounding the band at the time that is special. Seeing Stones members reliving past experiences via filmmaking equipment (and seeing their purest reactions) is part of the story; Gimme Shelter’s direct approach to a group of musicians facing the backlash of society and the marring of one’s image via the media is now a major staple of their legacy.

83. High School

If there was a verité director that really couldn’t care less about how subjects come off on screen, it was Frederick Wiseman, who let the power-hungry rulings of a Philadelphia school create the entire foundations of High School. Of course, teenage students are trying to figure themselves out and might misbehave, but seeing the guilt-tripping methods of authority back in the ‘60s is still uneasy to watch. On the other hand, there is also a lot of optimism in High School, with the teachers who do care to go the extra mile to help the troubled kids, and the students that still believe there is a bright future ahead of them (the disgruntled adults would prove otherwise).

82. Stories We Tell

Sarah Polley has an affinity for creating the exact feeling of unconditional love (see Away From Her). Her masterful documentary Stories We Tell never ever plays the blame game, even though that is a definite concern that some of her interviewed family members have. Polley wants to share her loved ones with the world first, and then get down to brass tacks about her real father. It’s such an unusual achievement that Stories We Tell can be centred almost entirely about an affair that has just been revealed, and yet no one feels dragged down in the mud; Polley’s picture feels like it was just life taking its course. Either the film was a way for Polley to rack her brain around her discovery or a means of cherishing her kin in the best way she knew how; whatever it is, Stories We Tell is brilliant filmmaking.

81. Le Joli Mai

Somehow, Chris Marker can extract so much meaning out of such little footage (he really directs as a photographer first: by getting a thousand words out of one sole shot). For over two hours, Le Joli Mai just ventures around Paris, finding citizens during their springtime excursions. The kicker is that France is finally devoid of being a part of any form of war, as the Algerian War had just wrapped up mere months before. Maybe Marker wanted to find a new side of Paris that was just revealed, or perhaps he feared that this was only a temporary moment of peace that was surely going to end in the near future. Either way, Le Joli Mai is an open floor for minds that are no longer bogged down explicitly by politics and war.

80. For Sama

How do you tell your child that their place of birth is troubled beyond repair, despite your best efforts? For Sama has mother Waad Al-Kateab fearing multiple worsts as her doctor husband tends to the hurt and dying in one of the last hospitals in Syria. Will they make it out of this nightmare? Will their daughter be born, and will she be safe? The purpose of For Sama shifts throughout the picture; even if you are seeing everything in hindsight, you still fear every second, because of how close you are to danger. There’s a reason why this moving visual diary is the most successful documentary in BAFTA history: it is impossible to not feel connected and astonished by.

79. The Sorrow and the Pity

Possibly known for its use of a punchline in Annie Hall, one might be able to call Marcel Ophuls’ The Sorrow and the Pity challenging. Both parts of this Nazi documentary focus on different vantage points (primarily politician Pierre Mendès France and journalist Christian de la Mazière) and the snapshots of Vichy France’s allowance of Naziism. It’s so intriguing to see the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust from this angle: how did we even get to these places? Parts of The Sorrow and the Pity are just as expected: confirmations of the public that didn’t agree. The rest is terrifying: a naivety that runs present throughout every government even to this day.

78. American Movie

Most cinephiles would love to have their dream film made. For Mark Borchardt, this meant Coven: a schlocky Z-film horror short. For Chris Smith, this meant American Movie: the capturing of Borchardt’s now-iconic production from hell. The amount of heart found in this quirky picture helps remind us that making films isn’t just about the passion: it’s about being fortunate enough to have all of the necessary elements. This includes proper equipment, willing cast and crew, and more. So much goes against the Coven production, as we can clearly see. Luckily, Smith took a loss and turned Borchardt’s experience into a piece of pop culture. We’ve all lived American Movie in some sort of a way: a failing dream whose experience’s longevity made up for the end result.

77. The Look of Silence

After Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing provided a whole new identity for the documentary genre, he wasn’t willing to stop there (or with providing information on the Indonesian genocides of the ‘60s). This time around, he provides a voice to the brother of a murdered victim of this purge. The Look of Silence takes a man with questions, and allows him to give his brother’s killers eye exams. In their delirious state and with their guards down, he begins to interview them. Imagine being face-to-face with those responsible for the death of a loved one; The Look of Silence documents these insane circumstances with discussions unlike any you’ve ever heard before.

76. Style Wars

We might know everything about hip hop culture now, thanks to the internet. However, there’s something fascinating with watching a documentary about the Golden Age of rap shot right at the start of hip hop’s mainstream rise. Style Wars was released in 1983, and was meant to contextualize street art, breakdancing, and hip hop itself. Tony Silver has an unbiased approach, allowing naysayers and hip hop worshippers to all have a say for the world to hear (Style Wars was released through PBS). What was meant to be an educational tool for a rising lifestyle is now a snippet of the culture itself; Style Wars was only the very beginning, and its curiosity is oddly endearing, given the mammoth size of rap culture now.

75. Salt for Svanetia

There’s no wonder as to why Mikhail Kalatozov was targeted to make propagandistic films at the height of his career. Even at the very start, he was a one-of-a-kind director that highlighted politics and his home nation unlike any other. Salt for Svanetia is part truthful documentary (about the salt droughts of a Svani community) and part artistic embellishment. Kalatozov gets a little carried away with the glorious shots he takes and the devastating grand finale (which isn't complete without the use of lactation to try and bring salt back to one’s soil, and a dog finding salt in a dead baby’s blood, amongst other aesthetic “sacrifices” [all staged]). I can’t help but love him for this: his directive was to bring awareness, and he did so in the way he knew how (albeit very fictitiously).

74. Encounters at the End of the World

Some of Werner Herzog’s best documentaries are when the director sits back and does zero work; his belief is that documentary filmmaking is best undeterred by a manipulator, as to capture ideas and events as naturally as possible. The purpose of Encounters at the End of the World is to bring people to Antarctica (because, let’s face it, most of us will never go to the loneliest continent on Earth). We discover how researchers get by down there, and we are also made acquainted with the endless landscapes and unique lifeforms there. Encounters at the End of the World isn’t full on verité, however, as Herzog is using this opportunity to ask as much as he can (why not? This isn’t exactly a common opportunity). His inquiries benefit all of us, both intellectually and with a breathtaking experience.

73. News From Home

Chantal Akerman uses the linearity of life in her films, unlike any other director before or after her. Part of her goal is to show pressing issues or natural occurrences exactly as they are, using cinema merely as a conveyance for her to share through. News from Home is how Akerman conjures up thoughts in her head as she reads her mother’s letters, sent to her from Brussels. Akerman herself was situated in New York City at the time, so we see her frequent sights; her current reality greatly contrasts with the words from France, creating a distance between Akerman and the woman she once was. News from Home’s very-literal pace allows your mind to wander, and you're always brought back to the grey area between identities. Is home Brussels, where the letters are coming from? Or is home New York City, and the film is Akerman’s news for us to pick up on? I believe the title refers to both.

72. A Time for Burning

While documentaries can be informative, they can also act as time capsules. I feel like William C. Jersey made A Time for Burning to either show progress in society, or to keep a hateful time in celluloid form as evidence. Sadly, the film falls in the latter category, as the duration of the film is devoted to a Lutheran minister’s attempts to include African American members in his church related events. The rampant racism throughout A Time for Burning is frankly despicable, and it pains me to see such an important quest be stifled by prejudice. One thing’s true, and it helps me feel better about the documentary. Even though A Time for Burning highlights the bigots of America, it also sheds light on those that will do anything to help cure society of its hate.

71. Si j'avais quatre dromadaires

After La Jetée reinvented the definition of “motion picture”, Chris Marker had to apply this same success to his own life (the short’s photographs were his own, after all). Si j'avais quatre dromadaires is a slideshow unlike any other: Marker’s own way of providing his own words to each photograph, as to cut down on the thousand or so we could have come up with ourselves. As per usual with Marker, nothing is exactly literal, and you go down some enlightening trains of thought, including religion, politics, and existentialism. In a way, this documentary only showcases Marker’s ways of thinking, which can narrow down the scope of the picture. But then, that means Si j'avais quatre dromadaires is really limitless as well, considering Marker utilizes a stream-of-consciousness to challenge your personal descriptions of his own pictures, thus creating an amalgamation of meaning.

70. The Murder of Fred Hampton

Fred Hampton’s name is surely a well known one now, thanks to the highlighting of the work of the great activists of history, and the recent release of Judas and the Black Messiah. The greatest representation of his work is The Murder of Fred Hampton, where you hear from the civil rights icon himself. Production started before he was slain by the Chicago Police Department, so the goal of this documentary shifted: from setting the score for what work Hampton actually does to get rid of misconceptions, to honouring his name and proving he was unjustly murdered. You cannot get more in depth on Hampton as an important figure, or the unfortunate circumstances surrounding his death, than this deeply personal documentary.

69. Faces Places

Towards the end of her career, Agnès Varda was still as youthful as ever, and she couldn’t have been more connected with the current state of cinema. She teamed up with the mysterious photographical artist JR to make Faces Places, which captures the humble lives of local civilians in such a unique way. There is something to be said about seeing your neighbours plastered onto a wall in such a scale, and then seeing how this mural is framed by the cinematic lens. All of this reshaping of local legacies gets Varda reminiscing about her entire life, allowing JR to bond with her and that’s when Faces Places really becomes a documentary for the ages; I can’t forget what Godard did to Varda in one of her final years alive, however.

68. Berlin: Symphony of a Great City

European documentaries of the ‘20s were such a unique kind of filmmaking, because they are mutts, birthed by the dawn of cinema and how everyday life could be put onto a big screen, as well as the new direction of art film and where the medium can go aesthetically. One such case is near the top of this list (not many guesses as to what it can be), but one other great example is Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, where the titular location is made into a visual masterpiece in as many ways as possible. This key example of the city symphony genre is still fascinating to watch today, even if it doesn’t get mentioned as much as that certain other film (more on that much later).

67. Tarnation

Tarnation is as fragmented as a documentary can be, which shares both director Jonathan Caouette depersonalization disorder, and his mother’s failing mental health. Made up entirely of home footage (mostly the cassette kinds), answering machine messages, and whatever effects iMovie could bring you, Tarnation tells a large story about growing up in a family condemned by mental illness, via the methods of the cinematic underground. As far as personal documentaries go, not many feel as authentically self-made as Tarnation, especially considering how much of it is pieced together by the recorded evidence of one’s own existence. It’s a difficult watch, but one of the more singular documentary experiences out there.

66. The Mystery of Picasso

Documentaries don’t necessarily have to be about social issues or current events, or even personal recounts. They just have to capture anything in life as is. On paper, The Mystery of Picasso likely won’t be the cup-of-tea of everyone; it’s literally a film mostly comprised of Pablo Picasso illustrating works in front of our very eyes (done in a reverse way, so we can see his art being done without anyone or anything in the way). For me, it’s a hypnotic experience, and a whole new way to frame said artwork: through the lens of a camera. Picasso himself made these pieces strictly for this documentary, so this is a moving art gallery of sorts; he successfully found a new way for art to be both temporal and permanent.

65. Decasia

There isn’t much to Decasia in the simplest of descriptions: Bill Morrison just shows deteriorated film for just over an hour. Aesthetically, Decasia is still a brilliant experience to watch, especially when paired up with an epic score. However, there is something so much deeper here, as if we’re consoling the cinematic medium for its inevitable, physical demise (the film was released just after the turn of the twenty first century, when digital filmmaking completed its takeover). These films will never be mended, but they’re weirdly preserved here: in the very digital medium that rendered film stock endangered in the first place. Decasia is both a blessing and a curse.

64. The Battle of Chile

Patricio Guzmán’s three part documentary epic The Battle of Chile (split into its separate parts over the course of the late 1970’s) is an unnerving depiction of political turmoil unlike any you’ve seen before. The film covers almost every single molecule of the 1973 Chilean revolution against Salvador Allende, and Guzmán makes sure to get the opinions of all: from journalists to fighters, the government and innocent witnesses. Over the course of this numerous hour affair, The Battle of Chile is always right in the line of fire, making for a confrontational angle of war that you will never forget.

63. Word Is Out: Stories of Some of Our Lives

Back in 1977, Word Is Out: Stories of Some of Our Lives was as direct as a film could be about the LGBTQ+ experience: how society treated members, what stigmas had to be shed, and the uphill battles the interviewees have had to face on a constant basis. In 2021, this is a documented time capsule in a world that is more ready to listen, and the film does a tremendous job at holding up as a clear message for nonmembers to hear (everything said here is still relevant today. Everything). There is still so much work to do when it comes to treating LGBTQ+ people right, and Word Is Out: Stories of Some of Our Lives will be there to help every step of the way.

62. The Great White Silence

Back during the age of silent cinema, there weren’t many pieces of evidence for people to see the scope of Antarctica, but Herbert Ponting’s The Great White Silence aimed to be the de facto main cinematic resource of uniting audiences with this mysterious continent, via the documentation of the Terra Nova Expedition. Today, the film reads almost like a work of art, as the pictures of massive glaciers and endless snowy landscapes are beyond gorgeous to look at. The entire trek is displayed so elegantly; if anyone was going to record this journey, it had to be done right, and by God was it ever.

61. When We Were Kings

The fight between George Foreman and Muhammad Ali in Zaire — known, obviously, as the “Rumble in the Jungle” — was the event of a life time for many. Leon Gast knew that this singular match had to be made perfectly, because there just isn’t an opportunity to do this ever again, so When We Were Kings took over twenty years to piece together and release. This labour of love was worth it, as we now have an ambitious retelling of this one-night affair, with so many interviews, and all of the buildup that was needed to recreate the sensation of this evening, for those who never had a chance to witness it for themselves. As far as sports pictures go, When We Were Kings is one of the more authentic simulations of the industry’s infectious energies and blistering triumphs.

60. Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse

Sometimes, a documentary about the process of making a film is better than said film itself. Well, okay, that is a nearly impossible achievement for Hearts of Darkness to pull off, considering it is about Apocalypse Now, but it’s still a brilliant documentary nonetheless. Filmed as if it was meant to be a piece of evidence in case something catastrophic happened during production, Hearts of Darkness is a constant flow of situations, each one worse than the previous. Eleanor Coppola (and company) focus on her husband Francis and the madness he exhibited during the making of this iconic war epic in a way that feels unbelievable to explain; luckily, the proof is right here, and Hearts of Darkness is a thrilling ride of its own.

59. Pina

Pina was intended to be Wim Wenders’ way of showing his appreciation for the genius choreographer Pina Bausch; she passed away before he could honour her with this gift of a film. Still, he was encouraged to keep going, and managed to replicate the brilliance of her artistry in this 3D series of dance-art manifestations, whether they exist on a stage, or they make the world their stage. The message was that Bausch’s possibilities were endless, and you certainly get that statement loud and clear with the imagination found here (whether it’s Bausch’s initial ideas being brought back, or Wenders’ framing of her work). You don’t have to be into dance to be blown away by Pina: a contemporary documentary masterpiece.

58. 4 Little Girls

Spike Lee infuses documentary elements into a number of his features, so it’s clear that he was meant to be making films that capture reality from the start. If we were to all of his documentaries to select his opus of that nature, it would have to be his first doc 4 Little Girls: the retelling of how four young black girls were killed in an act of terror in 1963. We view the build up to this bombing, and see the aftermath: the community is still shaken over thirty years later, as shown in the film. Lee’s point is that racism still exists, and the possibility of this happening again leaves so many people and communities feeling threatened to this day. It’s coming up to an additional thirty years after 4 Little Girls was made, and it sadly is still needed to be heard loud and clear.

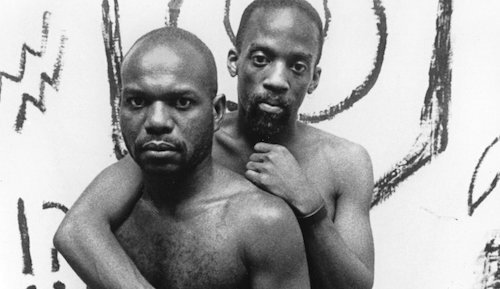

57. Tongues Untied

Fifty five minutes was all Marlon T. Riggs needed to create a documentary experience that couldn’t be forgotten. Maybe it was barely listened to upon release (outside of the LGBTQ+ community), but its importance has only allowed its legacy to grow for decades; now, it’s being shown in film festivals and placed on streaming services. Riggs blends spoken poetry and indie filmmaking to create a powerful depiction of what it was like to be a gay black man during the height of the AIDS crisis, with juxtaposed images of conflicting images; for instance, Eddie Murphy, whose homophobic routine was beloved upon release (and when Tongues Untied was made in 1989), but its problematic nature is widely agreed upon now. There’s only so many other uncomfortable truths needing to be heard where that came from.

56. The Gleaners and I

One person’s trash is another person’s treasure; that’s what they say, anyway. Agnès Varda shows a little bit of this notion in The Gleaners and I, which focuses on people who dumpster dive or locate thrown away objects to repurpose. Varda herself is looking much further, and is observing the complexities of the cinematic medium itself; the footage of her recording herself via her personal camera is adorable, but it’s also poignant. Is this film comprised of the scraps of footage Varda had while she was shooting video of her neighbourhood? Whatever The Gleaners and I is, it’s further evidence that Varda could find the heart of any subject matter, and share it with the world via film.

55. Water and Power

Sometimes, the most unconventional methods are the best ways to get direct points across. The title of the film Water and Power is the only purely straight forward element about it, but Pat O’Neill does everything in his power to sell his argument that Los Angeles willingly wastes its resources, and is killing nature around us. Using a whole myriad of editing, filming, and conceptual techniques, O’Neill has crafted a nearly avant-garde picture of the Earth’s natural gifts, and the human-made technology that has killed everything around it (and will lead to killing us, too). For a whole hour, Water and Power will put you in a trance, and shock you to your core at the same time.

54. Harlan County, USA

Barbara Kopple is iconic for her ability to capture aspects of the ways of the United States that many of us overlook, in ways that we can all understand. One of the greatest examples of this is her award winning documentary Harlan County, USA, where a year-long push against corporative greed tells a lot about the prioritization of profit and power over lives and the wellbeing of workers. The film is shot so passively, allowing everything in front of us to tell the entire story (without post editing biases); the end result is full of so many nuances and textures, begging for you to sort through and find new truths within.

53. Exit Through the Gift Shop

Exit Through the Gift Shop is either Banksy’s cinematic opus (his only main foray into film, to be fair), or it’s perhaps his greatest prank to date. Still, we aren’t certain if this documentary is even entirely true, because there are too many clues that it is a slice of meta commentary. The title implies we’ve been taken for a ride, and are brought to the conclusion of said experience. Enough of the subjects in the film can’t believe this is even happening, or they aren’t fully on board. Hell, the artist this film is based on is named Mr. Brainwash. If this is a staged piece on street art, it’s still a documentary in the sense that Banksy has captured the zeitgeist of the modern state of the art world. If not, then Exit Through the Gift Shop is evidence that life really can be this peculiar.

52. Buena Vista Social Club

Buena Vista Social Club requires some much needed backstory. Guitarist Ry Cooder collected a variety of Cuban musicians to recored the album of the same name, in order to recreate pre-revolution music in this autonomous space. Wim Wenders goes one step further and records all of this (the performances, and the creation of this project via behind-the-scenes footage) in his strongest documentary yet. You learn a little bit through the testimonies in between songs, but you will be so deeply enriched by this music, which had been waiting decades to be felt and loved. Buena Vista Social Club is as heartfelt as a musical documentary can get.

51. Salesman

Of all of the cinema verité experiments that the trio of Albert and David Maysles, and Charlotte Zwerin, achieved, Salesman might be their greatest, particularly because of how effortless it feels. It seems like their only objective was to follow Bible salesmen around, as they visit each house, yet this yielded so many results in such a short amount of time; each reaction is so starkly different, in response to the same pitches. Distancing religious beliefs from one’s interpretation, you’ll find something much deeper: the relentless pursuit of succeeding in America, only to be let down by the idea of its dream time and time again.

50. ¡Que viva México!

Films like ¡Que viva México! really test the title of “documentary” as much as possible; many likely wouldn’t consider this a documentary at all, but allow me to defend my selection of the film here. In a sense, Sergei Eisenstein’s incomplete project was meant to capture the essence of Mexico, blending documentary footage and set up scenarios. Then, the 1979 reconstruction of the film pieces as much as possible back together, like an archeological dig of this unfinished masterpiece, as if this lens itself is documenting this process and end result. It seems like a stretch, but the unique story and assembly behind ¡Que viva México! didn’t feel quite normal to place on my features list, so I’m giving it a home here as the furthest extension of what a documentary can be.

49. D’Est

Chantal Akerman is the queen of capturing momentary stillness, and turning the real lengths of time it takes to do something into art. These talents could only come in handy when she set out to capture the unrest of the disintegration of the Eastern Bloc, as Akerman frames people, locations, and events as if everything were trapped in limbo. More like a series of moving photographs than a film with a story, D’Est is as sublime as documentary filmmaking can be; Akerman’s style feels almost effortless, but you don’t see many other auteurs pulling off this kind of gargantuan minimalism, right?

48. Monterey Pop

The concert films of the ‘60s are indisputably the finest of the genre, and we will get to a few more later on. Something like Monterey Pop is a stellar example, because it is graced with amazing musicians and particularly outstanding sets (Jimi Hendrix notoriously lighting his guitar on fire comes to mind). The one advantage D. A. Pennebaker’s film has is the inclusion of then-contemporary art to turn Monterey Pop into a full-on depiction of the era, and not just the music that graced its inhabitants. This art helps sell the driving purpose of the film: it’s not about watching what you expect (like The Who kicking ass), but what unexpected elements will change you forever (that titanic closing number by Ravi Shankar, who, frankly, steals the entire picture).

47. Titicut Follies

When a point is to be made, some essays or arguments have a lot of time put into them, to try and persuade a specific angle. When a topic is as clearly problematic as the one at the heart of Titicut Follies (the abuse and neglect of criminally insane patients of a correctional facility), someone like Frederick Wiseman doesn’t need to say anything at all. Shot directly and without any outside cinematic influence, Titicut Follies just hands over what it captures (as is), and lets you see everything for yourself. There is virtually nothing anyone could have done to make the devastating footage any easier to witness; there’s nothing like seeing a film of this nature, and never being able to forget just how twisted our world really is.

46. Waltz with Bashir

How does a war veteran recount their time in combat if their brain has decided to remove that part of their memory bank? Soldier-turned-director Ari Folman tries to do just that with Waltz with Bashir, and the end result is a Flash animated wonderland that fuses his interviews with his deepest nightmares. As Folman begins to recollect what happened during his time serving in the Lebanon War, the more warped the film itself begins to be; this is a look at the mind of someone who is reliving their traumatic experiences in full effect. You might consider Waltz with Bashir a daring animated film. This is true. I’d go on record to call it an even bolder documentary.

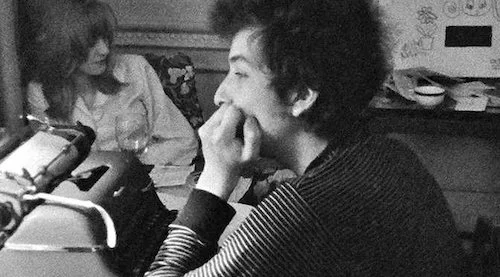

45. Don’t Look Back

Bob Dylan was such a mysterious figure during his prime in the ‘60s and ‘70s (he arguably still is difficult to describe as a person, considering his reclusiveness), so something like D. A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back was meant to clear the air. As is evident in the documentary, Dylan was still being misunderstood, regardless of the numerous attempts to spell out who he is to the world. Whether he’s being targeted for his electric period, or cast in a bad light because of his refusal to entertain loaded questions by slanted journalists, Bob Dylan still is one of rock music’s most enigmatic poets. With the best efforts of Don’t Look Back, Dylan wasn’t exactly defined, but the film around him became a lot more singular.

44. 13th

A big-enough topic and a masterful filmmaker are all that a documentary needs, sometimes. At its core, 13th almost feels like a very well done Powerpoint presentation, given its “slide” feel and division into parts. With Ava DuVernay at the helm, this seminar is an unforgettable one, especially because of how eye opening it is. Given that it’s about systemic racism that is still heavily present in America — because of the loopholes found in the United States Constitution — this is a very important lesson to attend. DuVernay reveals sickening fact after sickening fact, and by the time you’re ready to keel over from the realities you weren’t aware of before, you’ll find you’ve only been watching for half an hour, and DuVernay has so much more information where that came from.

43. Häxan

A documentary like Benjamin Christensen’s opus Häxan feels almost insane to watch. This silent masterpiece was meant to represent how mental illnesses have been misunderstood since the Middle Ages as connections to religion-based blemishes in a person (either through possession or blasphemy), and it goes all out. As if Christensen set out to create the greatest hyperboles of all time, Häxan is elaborate with its staged sequences, including Christensen playing Satan; these theatrics really drive the point home that some of these stigmas surrounding the mentally ill truly were bonkers, and that people should feel bad for punishing the needy in this way. As well intentioned as it is frightening, Häxan is one of the most unique cinematic experiences you may ever have.

42. Lessons of Darkness

As much as Werner Herzog loves making feature films, I feel like documentaries are where he feels the most accomplished, as he can allow his works to convey what he cannot put into words. Something like Lessons of Darkness feels like a film that only Herzog could make, as its subject matter is so grim that I can’t imagine many other filmmakers wanting to even approach it. Yet, here Herzog was, framing the complete destruction of the Kuwaitian oil fires (which appear to be never ending), and finding that nature’s wrath against civilization is a profound statement he had to share. As if we’re staring at the apocalypse, Lessons of Darkness is such a damning experience.

41. Citizenfour

Not many documentaries have changed the current technological landscape quite like Laura Poitras’ Citizenfour has (to this day, I still have a sticker on my laptop camera, and try to utilize Edward Snowden’s suggestions of “pass-phrases” instead of passwords). Released just in the nick of time, Citizenfour was as contemporaneously relevant as the film could get: the famous pictures of Snowden’s interview were matched with the reverse side of the situation, as we live locked up in a hotel room with Snowden before, during, and after his leaking of confidential information about the National Security Agency. Filmed as a piece of evidence in case anything happened, Citizenfour still feels like a political thriller to this day, because far too much of it continues to frighten me even eight years later.

40. Man on Wire

I think any documentary about tight rope walking would be interesting, because of the amount of filmmaking possibilities that arise from this premise (great shots, nerve wracking content, and triumph). When you incorporate the artistic stunt of Philippe Petit — where he crossed between both Twin Towers illegally — you get a film for the ages. Man on Wire is a strong film made nearly perfectly by James Marsh, who wanted to use this opportunity to flex his filmmaking skills (by creating reenactments of the big day, which get juxtaposed with real footage of one of the most exhilarating dares in American history). If there was ever a film that could match this kind of event, then Man on Wire is said film.

39. In Spring

For nearly eighty years, In Spring was just one of the countless avant-garde looks at the world around us back from the silent age; this is because it was deemed lost until 2005. Now, it’s a visual masterpiece that frames the titular season as one of the greatest events of nature, life, and the inner workings of a city. Mikhail Kaufman was clearly following suit in older brother Dziga Vertov’s footsteps (more on him later on in this list) when he made this photographical symphony that frames all things beautiful, majestic, impactful, or noteworthy; as a silent observer that doesn’t interfere with all of these graces.

38. Daguerréotypes

It takes a lot for auteur Agnés Varda to stop filmmaking, and I mean basically nothing could make her quit. As a new mother, Varda didn’t want to veer away from this part of her life, but she still wished to make films. So Daguerréotypes was made, and it’s one of her documentary masterworks. She captures the local lives as sincerely as possible, turning these lives into a living photo album that we could actually enter and witness firsthand. These subjects are given the same series of questions, and we get a myriad of results back. These are all players of life, but for a mere hour and twenty minutes, these are the members of Varda’s domestic orchestra, as they all turn everyday life into something monumental.

37. Warrendale

Allan King was tasked with showing how children within an institution for the mentally disturbed lived, and his work was meant to show on CBC. When the station refused to censor these deeply uncomfortable findings, King took Warrendale to the film festival circuit. I can’t even clearly state that he had a mission with this film and his persistence to show it, since the verité style allowed everything to take place with zero prompting. Outside of showing the abuse that takes place in these facilities, Warrendale is an outsider perspective of a world that many of us have never seen before; upon even one viewing, it’s a glance that we will never forget.

36. Minding the Gap

Bing Liu was just taping himself and his pals skateboarding, as was all the rage once upon a time. His love for filmmaking continued, and he found that his capturing of the real was his calling. Minding the Gap follows the diverging paths of this trio of best friends as their lives all ended up differently, but the pugnacious nature of skateboarding was kept throughout this documentary; how many confrontations can we face, and can we admit when we have done wrong the same way we can face those who have wronged us? Minding the Gap could have just been the retelling of hobbies or a specific topic like so many other documentaries, but it ended up being uncontainable; it bursts at the seams telling this triptych of entire lifetimes.

35. Hearts and Minds

I think it’s much easier to discuss the complex nature of the Vietnam War now than it once was, but that didn’t deter Peter Davis from going all in with Hearts and Minds: a documentary that gave zero cares about the naysaying it was due to draw. Its revelations of some of the darker truths of what soldiers went through during this war still feels startling; despite how often-discussed it now is, seeing the veteran at the end feel confused during a “welcome home” parade that ignored his concerns will forever haunt me. It’s telling that Hearts and Minds needed to jump many hurdles to be shown, but now it is preserved by the Library of Congress.

34. For All Mankind

There is borderline zero premise to Al Reinert’s majestic For All Mankind, outside of sharing the moon missions that NASA ran for a few years. Paired up with Brian and Roger Eno’s iconic soundtrack (which has been referenced in many places, from Traffic to Burial’s debut album), the images of the moon in this great detail is honestly jaw dropping. Do you even need any more than this? For All Mankind runs for only eighty minutes, but I could have gone with a four hour cut of this riveting excursion from life; everything and anything difficult feels menial after watching this film.

33. The Times of Harvey Milk

The life of Harvey Milk has been shared around frequently in recent years, either because of progressing times or of contemporary retellings (like Gus Van Sant’s fantastic Milk biopic), but the strongest capturing of his triumphs and unfortunate assassination are captured in this Rob Epstein masterpiece. The Times of Harvey Milk was released only a few years after Milk’s death, so the film wasted no time to keep his hard work and perseverance in the minds of citizens all across America. As sad as this tale is, it’s something to see how loving Milk was, and what promise he showed; this film excels with getting us as familiar with the late supervisor of San Francisco.

32. Grizzly Man

Considering how many documentaries Werner Herzog has made, it seems difficult to try and crown his opus of this medium. At the same time, it clearly feels like Grizzly Man, because of the insurmountable amount of achievements that this picture pulls off. Herzog makes a memoir out of Timothy Treadwell’s countless cassettes shot while he embraced nature and lived out in the wild amongst grizzly bears; this is all told in hindsight after Treadwell was killed by one of these bears. Out of all of the rules Herzog broke, I am the most glad that he refused to show Treadwell’s final moments like many other more exploitational filmmakers would feel compelled to do. Herzog sought out to find beauty and answers in this most unusual of lives, not to point fingers of blame.

31. O.J.: Made in America

You can say that the trial of one O.J. Simpson has dominated television for decades, whether it’s the trial itself, the American Crime Story miniseries, or this titanic ESPN documentary that absolutely needed to be close to eight hours long. Ezra Edelman’s achievement builds up the political tension in America at the same time as Simpson’s fame rose as well, only for both storylines to converge at the time of his murder charges. With the state of the United States in the backs of our minds as this trial goes on, it’s as if we’re reliving this infamous time in pop culture all over again. O.J.: Made in America is the retelling of what we already knew in the most definitive way, cementing this contemporary conflict as the epic that it was.

30. A Grin Without a Cat

I find Chris Marker loves working with brevity, so seeing how he would approach an epic cinematic essay like A Grin Without a Cat is quite the treat. This four hour behemoth that deconstructs the rise of various political movements (mainly the New Left party in France) by slapping together images in a more jarring fashion than one would usually associate with the sublime Marker; as if this was his time to be Sergei Eisenstein. As thematically nuanced as this film is, Marker’s unique style in A Grin Without a Cat makes for a dynamic visual ride, with each fragment carrying its own load of commentary.

29. Crumb

Cartoonist Robert Crumb has to be one of America’s most bizarre figures, because of his taboo artwork yet humble personality (which still feels like a paradox for the ages). Crumb feels like a great opportunity to find out where the art icon developed his style, and maybe this film could answer for his oddities as well. The end result is Terry Zwigoff’s documentary classic, which surprises us in a great way: Robert might be the most stable person in his family. We come for the analysis of a familiar face, but leave with this understanding of the entire Crumb family, and a reinterpretation of the American experience, warts and all.

28. Histoire(s) du cinéma

Out of all of the films Jean-Luc Godard released, it’s tough to pick his magnum opus. However, it’s extremely simple to point out his most ambitious idea: the monumental Histoire(s) du cinéma. This video essay was made over the course of ten years, and released in a series of parts, with every second of production time and the viewing experience devoted to the same mission: understanding cinema as art, an artifact, contemporary commentary, a device of history, and as the rewiring of one’s brain. No part of the film feels the same, and all four hours run like a stream of consciousness processed into video. Godard wraps up the entire project with striking clarity, which rewrites all of Histoire(s) du cinéma in a way that he vowed to change and challenge film for his entire career.

27. The Last Waltz

After decades of being the top group to work with for massive folk rock names (particularly Bob Dylan), it was time for the love to come back around for The Band. Martin Scorsese used The Last Waltz to give the iconic musicians the send off that their careers deserved, and what a party they received. The Band alone would have been amazing to watch, but seeing all of their pals (Dylan, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Muddy Waters, Van Morrison, and many more) join them is truly something; the collective version of “Helpless” never ceases to bring a tear to my eye. There are years of chemistry bottled into The Last Waltz, and no participant wastes a single second.

26. My Winnipeg

Out of all of Guy Maddin’s interesting works, there’s a reason why My Winnipeg resonates the loudest. He has always tried to reinvent silent or older cinema for a new audience (especially with largely surreal interjections and natures), but My Winnipeg sees the eccentric Canadian auteur reinventing the documentary. So everything in this film is true, to an extent; these events are true in the mind of a daydreaming, imaginative filmmaker. In actuality, we get a blending of fact, fiction, and all of the absurd chimeras spawned in between these two clearly distinctive sides of the grey area Maddin thrives in. It’s impossible to be bothered by the fabrications in My Winnipeg, because it’s all so bizarrely beautiful.

25. Baraka

After Ron Fricke helped shoot the documentary Koyaanisqatsi, he deemed that it was his turn to shine. His similar film Baraka features zero narration or subtitling, but every image carries such conversational weight to this larger statement about the state of the world throughout history. While not as darkly political as the followup Samsara (which is a nice continuation but not nearly as good), Baraka is moving enough, as we visit six continents and observe the ways of life of so many different communities (as well as the nature that surrounds them all, either unfazed or disturbed by humanity’s meddling). Baraka doesn’t have to explicitly say anything, because it visually says everything.

24. Grey Gardens

Grey Gardens is one of those works where context changes everything. Without knowing the histories of mother and daughter Edie Bouvier Beale (Big and Little, of course), you might find them amazingly magnetic, even with their disfunction. Learning that they are related to the Kennedys (yes, those Kennedys, through Jackie Onassis) just makes all of Grey Gardens really sad in a way, knowing that these loved ones have been left to fend for themselves with complete neglect. Mind you, their home has become one of the great locations of cinema, as both Edies made the most of their predicament: by making their own world and way of life. Parts of Grey Gardens might hurt, but the Bouvier Beales are just too loveable.

23. Stop Making Sense

There are many concert films, even ones that leave their mark (we have a few, here). Sometimes, all it takes is the right niche to render one iconic. That’s what Jonathan Demme’s singular Stop Making Sense achieves. The new wave group Talking Heads all enter the stage one by one (session musicians includes), song by song. David Byrne starts things off with an acoustic number, only to be joined by Tina Weymouth for a stripped down version of “Heaven”. A few songs in, and we’ve gone from a humble set to a massive celebratory freakout, stuffed with incredible musicianship, infectious energy, and every Byrne peculiarity under the sun (lest we forget the giant suit).

22. As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty

If you’re crowned one of the great avant-garde filmmakers of all time, it can only mean great things if you release a cinematic memoir of your entire life. That’s exactly what Jonas Mekas did with his experimental, five hour opus As I Was Moving Ahead Occasionally I Saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty. The film is as ambitious as this title, as we course through hours of Mekas’ home footage, and reassess his entire life, as if we’re hypothesizing his existence on the spot. Mekas doesn’t really go fully philosophical, but is willing to dive in head first as a poet, as this documentary epic feels like Mekas is exposing his entire soul for us, without a single fear in the world.

21. The War Game

Perhaps one of the greatest provocations of the documentary medium, I wasn’t sure if I felt comfortable even mentioning The War Game here at all. Sure, it pulled the wool over many eyes, including the Academy Awards (which awarded it as “Best Documentary”) and many critics, but Peter Watkins’ catastrophic war film is hardly compiled of real footage. Instead, I like to reinterpret this film as the documentation of what could happen, using current day fears and practices to bring these thoughts to reality. Whether you believe the events on screen or not, The War Game (and its depictions of nuclear warfare and its horrendous aftermaths) might be one of the more anxious film viewing experiences you’ll ever have.

20. Tokyo Olympiad

The Olympics and cinema go hand-in-hand, and the greatest sporting event of the world is always a great excuse to try and figure out new and exciting ways to shoot athletes in motion. Decades after Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia films, Kon Ichikawa was passed the figurative torch with his own achievement in sports cinema: Tokyo Olympiad. What makes his vision one of the best of these events is that every sport and athlete is shot with the exact same gaze, creating a work of art rather than the boasting of wins for any particular nation. For three hours, all that matters is the energy between the best athletes in the world, and the public that cannot believe how far we’ve come.

19. Welfare

The greatest film Frederick Wiseman has made (which says a lot) is the uninterrupted observation Welfare. If anything, this feels like such an invasion of privacy, as we watch uncomfortable conversations between people in need and welfare employees that can’t go against what they’re told to do. There are also discussions between all walks of life, which usually result in even more awkward revelations about the ways different classes are pitted against each other, how systemic bigotry plays favourites, and how we’re all made to hate each other while the elite thrive. Learning this much about humanity is always going to be devastating, and Welfare isn’t the easiest watch, but it’s a series of examples that everyone deserves to hear.

18. The Hour of the Furnaces

Revolutionary cinema is bound to be uncompromising, and the staggering political epic The Hour of the Furnaces is beyond harrowing. For four hours, Octavio Getino and Fernando Solanas toss us into the heat of powerful, startling images of Latin American politics of the ‘60s, proving to be one of the great pieces of the Third Cinema movement. Split into three parts and centred around infamous names like Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, somehow the height of social turmoil is made to look like great art (each section of this trilogy carries its own narrative of activist ideologies).

17. The Beaches of Agnès

Clearly, Agnès Varda is one of the great documentary filmmakers, since she has been featured here a number of times. Her look at everything in the world — from her neighbourhood to political commentary — will always be fascinating. However, her opus in this field is The Beaches of Agnès, where she finally turns the camera completely on herself (and not the usual glances we get). What was meant to be her final film, this cinematic memoir features an eighty year old legend reevaluating each and every step of her career with new wisdom and appreciation; in typical Varda fashion, everything she says is profound and eye opening.

16. Chronicle of a Summer

Confessions are such a special form of storytelling. Hearing someone reveal truths or memories in such a detailed way conjures up thoughts in your mind, as you get immersed and piece together every little nuance to better understand what you’re experiencing. In the interesting experiment Chronicle of a Summer, subjects are shot and asked a series of questions, only to be shown the cinematic evidence after the fact and revisited. Our memories are one thing, but the filmic gaze provides its own recounting of events in such an interesting way. Now, Chronicle of a Summer is the most eccentric of time capsules, since it isn’t solely the containment of the past, but it’s the analysis of what the past even is that is preserved.

15. F For Fake

Orson Welles developed such a personality and level of confidence ever since he even came into the film game. You could only imagine that thirty years later, that he was going to flaunt all of his charms and talents in what was to be his last masterpiece. He does just that with F for Fake, as he documents the crazy world of art forgery. As he lures you with his hypnotic voice and illusionary filmmaking, he puts you up to the ultimate test; most viewers will fail this. As if he was pulling a Banksy decades before the elusive icon came to be known, Welles accomplishes a major magic trick, resulting in both his ultimate statement on art and the gullible nature of the viewing public.

14. Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father

One of the most intense crime documentaries ever made is this tribute to fallen loved ones. Kurt Kuenne used Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father as the opportunity to highlight his best friend Andrew, who was murdered by his secretive partner he stopped seeing. I don’t want to say any more, because the story only gets more and more unbelievable from there on out. Seeing the rawest reactions from family members in this confrontational film is the kind of real severity that very few films can achieve. For legacy and for evidence, Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father is the best form of honour possible.

13. Koyaanisqatsi

Ever since Man With a Movie Camera, only one film has come even close to being as brilliant when it comes to turning the human civilization into a visual and musical symphony. Koyaanisqatsi is such a unique experience, that even each subsequent film — either made by director Godfrey Reggio or cinematographer Ron Fricke (which includes the stellar Baraka, of course) — isn’t quite at the same level. There’s something about the marriage of these glowing visuals (which live at different speeds) and Philip Glass’s score, that will place you in a trance that is impossible to break; the fact that a backwards playing version of Koyaanisqatsi is successful is proof of this. If there was ever such a thing as meditation bound by seeing life, technology, and nature, this would be it.

12. The T.A.M.I. Show

Sometimes, the need to cash in on the youth of today can turn out to be a beautiful thing. In all respects, The T.A.M.I. Show was meant to bring teenagers closer to the hit musicians of the early ‘60s, as a means of promoting new singles and albums. Instead, we get an exhilarating rush of joy and energy. This is achieved by each group and/or performer going all in; The Rolling Stones were famously dumbfounded to follow a perfect James Brown and the Famous Flames set. There’s also the cinematographic efforts that make each segment only better; the zooms and pans in a number like “Where Did our Love Go?” by The Supremes turns this performance into a music video before that concept was even fully realized. The T.A.M.I. Show is the perfect time machine trip back into the ‘60s, as the popular music of the world was greatly changing before our very ears.

11. The Thin Blue Line

Errol Morris was destined to make documentary films, and was well on his way to figuring out his capabilities after his debut Gates of Heaven. By his third film (The Thin Blue Line), he was all set, and developed a crime documentary for the ages. If anything, this film took the wrongful murder conviction of an innocent man (arrested in the mid ‘70s), proved his testimony by artistic recreations, and then presented a case that could be reassessed during the dawning of forensic DNA profiling. The success of The Thin Blue Line has become part of its legacy, but the film itself — so fascinatingly made — continues to reign as a crime film classic.

10. Paris is Burning

Once a year, the Paris is Burning ball was all that an entire neighbourhood had to look forward to, in a New York City that neglected each and every single member (persons of colour within the LGBTQ+ community). For one night (and the prep time that built up to it), every performer and audience member was a superstar, and the challenges of the world could be faced for another three hundred and sixty four other days. Jennie Livingston wanted to make sure this celebration lasted forever, and she preserved these joys in Paris is Burning. Alongside the fun of the titular event are the hardships that many people faced in a hateful America, especially during the AIDS crisis of the ‘80s. Over thirty years since its release, this documentary has opened eyes, changed vocabularies, and provided comfort and hope to the countless people that need it the most.

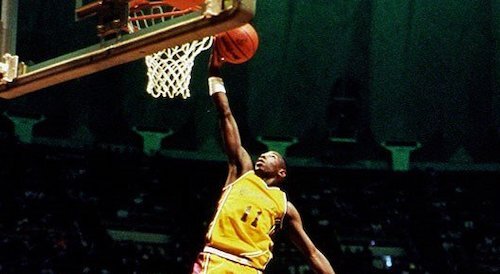

9. Hoop Dreams

Getting into the National Basketball Association (or any other major sporting league) is a blessing, but it’s a fortune of now. Sports weren’t always as well-paying or massive as they are now, but basketball seemed like the greatest thing on earth during the Michael Jordan era. In the cases of the two budding athletes Arthur Agee and William Gates, the NBA is the absolute end game, and Hoop Dreams hoped to be there when it happened. Of course, the biggest courts in the world was the final destination, and Hoop Dreams picks up on all of the difficulties along the way, from suffering neighbourhood conditions, to difficult lives at home. Still, for these three hours, you will be rooting for these two basketball prodigies to get to where they want to go, and you’ll find yourself right in the middle of one of the great sport films of all time.

8. Woodstock

There are so many phenomenal concert films, and I think one’s personal taste can dictate which are some of the better experiences. However, there’s just no way to insinuate that any music-based documentary is more accomplished than Woodstock. At nearly four hours (the rerelease, anyway), and with the goings-on juxtaposed with concert footage of the iconic festival (pieced together by editors like the future duo of Thelma Schoonmaker and Martin Scorsese), you feel like you get every single angle of this once-in-a-lifetime event. For every second, I felt so immersed, like I could smell the spilled alcohol or feel the sun’s hot ways (or my shoes squelching in the wet, deep mud). Now that Woodstock is over fifty years old, I think it’s settled: there may never be a better music documentary than Woodstock.

7. Close-Up

Out of all of Abbas Kiarostami’s shining achievements, Close-Up just might have to take the cake. The late Iranian auteur loved blending reality with fiction, and he struck gold with the strange case of Hossain Sabzian’s theft of the identity of director Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Kiarostami attends this trial in court as a witness, but grants everyone a brand new way to testify their sides of the story: Kiarostami filmed all of these events with every person performing as themselves. Mixing the courtroom footage with the recreations Kiarostami shot is one of the biggest strokes of genius in documentary history, and a blending of truths and confessions into one melting pot of perspective.

6. Olympia Parts 1 and 2

One of the most conflicting masterpieces in cinematic history is the two part Olympia series by Leni Riefenstahl. Released as Nazi propaganda during the 1936 Olympics of Germany, there is as much to adore about these films as there is to feel extremely uncomfortable with. Its revolutionary filmmaking techniques cannot be ignored though, ranging from its undeniable impact on sports cinema (slow motion replays), artistic cinema (the opening creations for both parts), and film as a whole (the myriad of ways that cameras could be incorporated for all of these live events). As films, both Olympia parts are breathtaking; it’s too bad they were tied to the ugliest agenda of contemporary history.

5. The Up Series

I did the research I needed to last year (2020) for this list, and that included catching up with, well, every single Up entry. To have 2021 start off with Michael Apted’s passing was so tragic. I feel like I was ready to keep going with his work and the many participants of this unbelievable documentary experiment (a group of seven year olds were filmed in 1964, and they have been documented for every seven years of their lives). Somehow, each entry of the Up series only gets better, as if Apted and original director Paul Almond were able to predict exactly the trajectories of these many young lives. I’m not sure where the series will go now, but one thing is for certain (especially in the face of so many spinoffs and imitators): this is a miraculous achievement of cinema that likely will never be duplicated in exactly the same rewarding way again.

4. Sans Soleil

As we’ve established many times on this list, Chris Marker was a singular auteur that was able to turn photographs into living moments, and these moments into the most fluid daydreams. His magnum opus (when it comes to documentaries, at least) is unquestionably Sans Soleil: an exercise in turning diary entries consisting of existential thoughts into one of the most profound video essays to date. Pitting Marker’s footage from his trips to the words spoken by Florence Delay is to know what deep thoughts will look like in a visual nature; never have gut feelings or wandering minds felt this profound, moving, or enlightening. Sans Soleil is all about the unreliability of memory, so it’s only ironic that this is a documentary you will never forget.

3. Man with a Movie Camera

It is mightily difficult to go up against the first documentary to be done perfectly, since Dziga Vertov set the tone with his avant-garde masterpiece Man with a Movie Camera. Usually, being the first (or one of the first) doesn’t matter to me if there are better examples, but there just aren’t many greater documentaries than this one. For slightly over an hour, Vertov has turned the cities of Russia into the finest cinematic landscapes of his time (and, to some, ever). The cinema of attractions of yesteryear was now transformed into the artistic, thrilling, experimental prism that has been possible ever since. Most documentaries try to shed light on information or ideas. Man with a Movie Camera took what we already knew, and made it the experience of our lives.

2. The Act of Killing

Rarely do recent films make as big of an impact in a medium like Joshua Oppenheimer’s unforgiving documentary opus The Act of Killing. It takes a lot for a film that (presently) isn’t even ten years old yet to be ranked second on an all time list, but everything in this feature is harrowing perfection. The premise alone is ingenious: Oppenheimer got several party members involved in the Indonesian genocides of the ‘60s — who are still currently proud of their murders — to reenact their slaughterings in cinematic ways (including the genre conventions of a colourful musical, a gritty gangster flick, and an exciting western). The audacity of this premise alone results in the gaze of the hateful unlike any film I’ve ever seen. The briefest signs of regret are just as challenging to see; the realization of one’s monstrosities (of this magnitude) is impossible to carry. By its design, boldness, and ruthlessness, The Act of Killing has already cemented itself as an unmatchable documentary experience.

1. Shoah

Set aside your subjective taste, and it’s still borderline impossible to try and place any documentary film above Shoah. What it accomplishes alone is impossible to ignore, and arguably hasn’t been met since. Claude Lanzmann used everything he could to tell the story of the Holocaust in great detail; keep in mind these events were only forty years old around the time that Shoah was released, and these horrors were still fresh in the minds of most viewers. Alain Resnais’ similar Night and Fog (which I haven’t forgotten; it’ll be featured on my top short films of all time) took thirty minutes to show us the harshest realities of what the Nazis did to humanity. Lanzmann needed much more to grapple the ghosts and demons of these events that still haunted the world, so he opted for ten hours. Even then, these ten hours don’t feel like they are enough. There will never be enough time to fully understand and accept what has happened within recent history.

Lanzmann visits survivors, finds onlookers, and even gets the words of former Nazis; everything is compiled into this gigantic recount of what went on in the concentration camps. Unlike Resnais’ incredibly graphic short, Shoah only relies on memories and recollections, and that only emphasizes the damning nature of the lingering dread caused by one of humanity’s worst hours. We see the grass that has grown throughout the train tracks that led honest people to being burned and/or tortured to death. We spot empty buildings that house nothing but unfortunate memories. Shoah frames forlorn glances, the pauses in between words and thoughts, and every single tear shed during these interviews. Documentaries are typically meant to bring real life onto the screen, and you won’t find any stronger captures of human history than this ambitious, determined experiment (which took eleven years to get just right, with hundreds of hours of footage to sort through).