Trainspotting: On-This-Day Thursday

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Every Thursday, an older film released on this opening weekend years ago will be reviewed. They can be classics, or simply popular films that happened to be released to the world on the same date.

For July 19th, we are going to have a look at Trainspotting.

Choose life.

Choose a job.

Choose a career.

Choose a family.

Choose a crisis to roll around in because it never gets any easier.

Choose a concern that you’ll have to deal with this week, and choose the way you will barely cope this time around.

Choose an identifiable piece of art that understands the complexities of life, no matter who is watching.

Choose a film with a message that frankly couldn’t give less of a care if you listen or not.

Choose Trainspotting: one of the greatest works of the ‘90s, because it understands consumerist addictions, millennium anguishes, judgmental societies, self destructions, and societal loathings more than any other film ever.

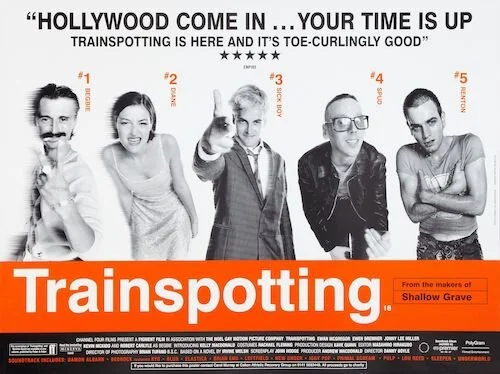

Danny Boyle had nothing to lose after Shallow Grave, and his follow up film Trainspotting felt like a film that was meant to shake up the medium. If anything, Trainspotting has become as much of a counterculture masterpiece as it is a large part of ‘90s pop culture. Trainspotting doesn’t rebel aesthetically (not with one of the greatest soundtracks ever, in any case), but rather in its tonal ambiguities. As funny as it is disturbing, Trainspotting is an incredibly difficult film to label, which feels perfect in a decade that was trying to label every film as much as possible during the early ages of the internet age. The film runs the risks of being misrepresented, usually as just a film about drugs, but that’s okay; no one gets penalized for considering the film in such a way. What I’d like to do, however, is drive the point home that Trainspotting is about a hell of a lot more than drugs, and its opening monologue by Mark Renton (Ewan McGregor in a breakout role) proves this.

Trainspotting juggles a series of topics effortlessly.

The title may seem weird, but that’s because the actual train spotting that happens in Irvine Welsh’s novel isn’t actually shown here. The title remains, because its symbolism is apposite. Why are drugs a major portion of the story if the film isn’t explicitly about drugs? Because Trainspotting is about the many things — usually unhealthy — that human beings do in order to feel that rush of life: that purpose for existing. An interest in drugs to spice things up develops into an addiction: a sensation that one will die (or, due to withdrawals, will die) if they don’t get that hit again. However, Trainspotting looks into many similar addictions people have, including various sexual pleasures, capitalistic greed, mind numbing programs, and more. We focus on Renton and his usual suspects, because society judges them. However, you can spot similar behaviours around them. If you can’t get by without coffee in the morning, you have a similar problem. Of course, heroin is incalculably worse, but both substances were taken to improve dull, depressing lives: one decision was just poorer than the other.

If you look at Begbie (Robert Carlyle) in this gang, he doesn’t even use heroin at all. However, he is an alcoholic, and he is unquestionably the worst member, particularly because of his abusive, explosive behaviour. I’d argue that Sick Boy (Johnny Lee Miller) has an addiction to proving he can kick heroin cold turkey, and then there’s Tommy (Kevin McKidd), who was drug free until he finally gives in, possibly as a fear of missing out. Even just drug addiction is observed in a variety of ways, but there are other chases of other highs, including a trek to “the great outdoors”, which results in a boring affair for the gang. There’s an obvious reason why Iggy Pop’s “Lust For Life” opens the film (outside of being one of the best uses of a song in a film), and that’s because every single person ever has tried to love life just a little more. We’re looking at a squad that chose badly, but they wished the same desires as the rest of us: a discovery of what it’s all for, why we are here, and how we can take this pain away.

Begbie is a horrendous person that poses as the film’s villain of sorts.

Boyle and screenwriter John Hodge understand that life has ups and downs, so Trainspotting couldn’t be any different. It finds both humour and wonder in the absurd, particularly through drug filled hallucinations (Renton having to dive into a filthy toilet for his suppositories, only to find an underwater wonderland) or aftermaths (let’s not get into Spud [Ewen Bremner] and the worst morning after ever). We also get an early look at Boyle’s affinity for peculiar storytelling, and it would define his brilliant career. It’s as if Boyle has taken inspiration from music videos and applied this level of imagination in regular feature films. He always ends up with exciting perspectives. Trainspotting was the perfect sandbox for him to experiment with, especially with the drug fuelled fantasies that can detail plot revelations in unpredictable ways.

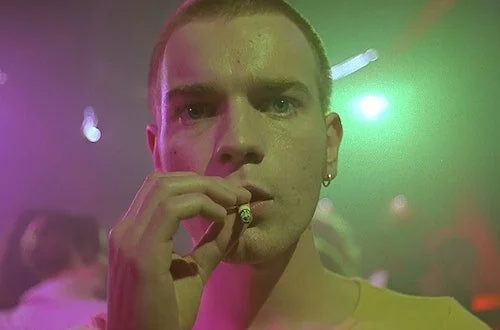

All of this follows Renton, of whom I’ve mentioned a few times. Renton is the star of the show, as we hear his inner thoughts and experience his unreliable forms of narration. What we can bank on is Renton’s experiences, even if we can’t trust the ways he tells these stories. He is wishing to quit heroin, and there is much doubt with this goal. In Boyle’s manically edited and shot opus, you can feel a frantic mind trying to fight off the cynicisms of naysayers, whilst distracting itself from the creeping urges to shoot up again. There’s a sense of relief whenever Renton gets high, including an unforgettable opening shot when he collapses to the floor with complete euphoria. The film follows Renton’s daydreaming in between hits, including moments where he seemingly hops from one shot to another, and other illusionary treats.

We follow Renton and his conflicting feelings of his heroin addicting: the urge to quit combats his need to get high again.

Trainspotting hits a turning point about two thirds through when Renton’s ambitions and quests pivot an entirely different idea: finding a new cause for existence. The film doesn’t lose any steam or identity, and this turn actually feels completely uniform with the rest of the picture. This is precisely why I think Trainspotting is about so much more than just watching addicts fight against their cravings. Even in the pursuit of living a normal life (a U.K. version of the American Dream, if you will), there is backstabbing, envy, and other detestable behaviours and moods. Life in any capacity isn’t regular. We’re all fighting to get up this ladder that humans countless of years before us set into place, as a means of improving the experience of living (when, really, we’ve made things much worse than just eating, drinking, mating, and excreting, despite the amazing accomplishments we’ve also developed). When Spud tries to throw a job interview in Trainspotting, it’s so he can live off of unemployment. This may seem like laziness. During the second year of a pandemic, many have learned that unemployment cheques pay better than many jobs do.

Regular life isn’t kind to anyone, either, and only the lucky and fortunate don’t have to be dragged across the asphalt of existence just to cope. We can gawk at the cast of characters in Trainspotting all we want, but they did what they felt was right to keep up. Many of the difficult realizations these characters have come post high, or even during bouts of withdrawal. The neglect of a child during a drug binge. A life thrown away whilst having nightmarish visions. Hell, even an overdose is shot tenderly (with Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day” crooning us to a fatal sleep), since the high is so good, and noting else matters. These brushes with death only make responsibilities and realities all the more difficult to accept, and letting these important factors deteriorate (or even die) solidify the worst elements of life. So, what is life worth fighting for? Trainspotting doesn’t quite have an answer to that, but it does suggest that you try to chase this proverbial high in the best, healthiest ways possible. Of course, life is still a game, and you may have to step on a few toes to succeed, but don’t destroy yourself just to explore yourself.

The funny moments of Trainspotting are a riot, but the dramatic portions are downright terrifying at times.

It’s no wonder why Trainspotting was so identifiable with most audiences back then, now, and in every college dorm or cinematheque in between. The film speaks to the youths of the ‘90s, either the identity-less teenagers who haven’t a clue as to where they should be in society, or the young adults that find out the hard way that you’ll never feel confident. It’s vital for older audiences who can look back at the paths they’ve taken so far, and can understand — to a degree — why these junkies put themselves through lives of hell for glimpses of joy. The human experience is a pugnacious one. We apply to many jobs that reject us. Try to find love in all of the wrong people. Go to open house viewings just to remind ourselves that we can never afford anything more than a rented condo (if we’re lucky). Hop onto social media just to see the highlight reels of other people (who are suffering their own existences, but will only show when they succeed) just to feel worse about ourselves. We keep trying to find the right things to do, and we punish ourselves in the process. We don’t have a choice.

With a gorgeous soundtrack, full of rock, britpop and electronica jams, colourful visuals set to unusual images or angles, and an eclectic cast that couldn’t have been better, Transpotting is an opus for misfits or unorthodox behaviours (we all can identify with some of those to varying degrees). Even if you’re not sure what to take away from this film morally, you can’t help but feel like you’ve witnessed an absolute treat of sound and vision, by an auteur that was aching to push boundaries from even this early on in his career. Trainspotting is daring but never anarchistic, out-there but always identifiable, and one of the rare films to capture the oddities of being alive (albeit in a very extreme way). Whether you watch the boys sprinting away from coppers, fights caused just for the fuck of it, or personal videos (of that nature) being juxtaposed with a game-winning goal in a sport, Trainspotting unites us all with that bliss we all adore: exhilaration. We don’t need to know what drugs are like (especially hard drugs) to understand Trainspotting. We just need to have been put in an unfavourable position by civilization, depressed or numb every day, and in dire need of even an iota of happiness. Trainspotting provides all of the highs and the lows.

So…

Choose life.

Choose whatever life means to you, as long as it doesn’t hurt yourself or others.

Choose the joy that only you yourself can seek or create, because life isn’t providing you any gifts any time soon.

Choose life, since being alive is not the same as living in a societal sense, and we have this one-time gift that we can cherish, despite humanity’s many woes.

Choose whatever will get you by.

Danny Boyle chose film.

He chose the book Trainspotting.

He chose life.

We all choose life.

Let’s choose life, and choose to get through this shit storm together, because it’s miserable for most of us.

Trainspotting reminds us that life is rough even for those without addictions, but those with addictions are going through a whole different kind of dark period.

Let’s choose life and choose each other’s lives, and get through this okay.

Life has been rough for me, like it has for you. I guess I chose to write about films.

That’s how I chose life.

I hope you find your choice as well.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.