M*A*S*H: Perfect Reception

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This is an entry in our Perfect Reception series. Submit your favourite television series for review here!

A great idea can go a long way. Having said that, many strong shows have been run into the ground after so many seasons that destroyed what was once a good thing. Due to success, numerous shows have become worse despite their great beginnings. In this case, there was one very distant starting point in the form of Richard Hooker’s novel MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors. Based on the Korean War of the ‘50s, this 1968 release was closer to the event than any other version that came afterwards. Still, the seeds were there amidst the pages: characters like Hawkeye and Radar, military doctors needing to pass the time in their own way, and a blending of darkness and light that would become synonymous with the acronym ever since.

Next came Robert Altman’s big breakthrough film M*A*S*H, and what it was celebrated for would be known as the auteur’s style from that moment forward: massive casts, counter Hollywood storytelling, and a blurring of genres to the point of indescribability. The film would win the Palme d’Or, and Altman was America’s next big voice who would go on to make some of the nation’s greatest works. As for M*A*S*H itself, I think it’s so funny to watch in hindsight, especially with how much of the lore was presented here. As an Altman film, M*A*S*H is really good. As a piece of the entire scope of the franchise, it’s just good enough. It sets the scene of the satirical antics of the medical military unit, as Altman’s commentary about the Vietnam War can be felt throughout the film. Otherwise, the scope of potential can be felt but not reached. Maybe because I’m both a massive fan of what was to come (for both Altman and M*A*S*H), but I view this film as a strong stepping stone.

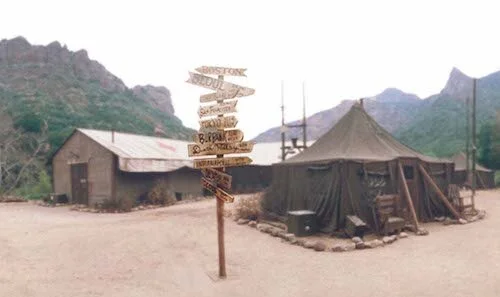

Finally came the show, which is why we’re here today. I think it goes without saying that I think the M*A*S*H television series is easily the best version of the story, but it’s also the medium that tiptoed the line of the boundaries of redundancy and exhaustion with so much confidence and boldness. Before we go the distance, let’s start from the beginning. Larry Gelbart was the main force behind the series at first, as the head writer for the pilot episode; clearly CBS wanted to cash in on the next possible sitcom. Only a couple of elements from the M*A*S*H film remained. The song “Suicide is Painless” — used humourously in Altman’s flick — was now an instrumental theme song that ushered in helicopters with wounded soldiers. Gary Burghoff remained as the character Radar, whilst virtually every other character was replaced by another performer. The series merged comedy and tragedy. That’s basically it.

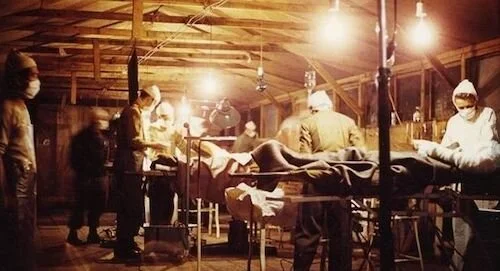

Not only was M*A*S*H not even remotely like its source materials for the most part, but M*A*S*H aimed not to be like situation comedies either. Gelbart hated that CBS forced a laugh track onto the series (Altman’s film did just fine without cackling howls following each moment), so he made a request that any scenes within the surgery room must not have this effect (even if Hawkeye passed a sarcastic remark). Thus began the dichotomy of the show: the silliness that doctors partook in to get by, and the horrors of war that forced them to try and find joy within life. Gelbart would stop being the main brains behind the project by the end of season four, and you can feel the notable shift in tone from there on for sure. Laughs were fewer and farther between (not because M*A*S*H was no longer funny, but because the show didn’t try to turn everything into a joke). The dark themes of death, violence, and anguish grew stronger and stronger. The relationships between characters were more notable. You lock the shtick of M*A*S*H into one single film and you have a question of “where can this go?”. Well, M*A*S*H the show vowed to explore every sensible (and inspirational) avenue.

The episodes themselves were mostly episodic, as was the standard for comedies (and even dramas) of the early ‘70s. A premise was given, explored, and resolved in twenty five minutes. You could watch at any time, and not worry about a lack of missing information from previous instalments. However, unlike many shows of its time, M*A*S*H rewarded viewers that tuned in either at the right time or all of the time. That’s how you got special one-offs like “The Interview”, which was presented as a documentary of medical units during war, “Point of View”, which was shown entirely from a first person perspective of a wounded soldier being brought in for surgery, “Life Time”, which had sequences presented in real time (and with a clock in the corner to show how many seconds are left to save a life), and the double “Comrades in Arms” episode where Hawkeye and Hot Lips are fighting for survival. M*A*S*H played by sitcom rules, but it vowed to test the genre’s limits as much as possible. There’s no comfort zone here.

Another kind of rewarding experience are the “Dear” episodes, where characters wrote letters back home to their loved ones. They would happen around once a season, and each version would be from a different voice. These were personal takes on character development that humanized these faces that we would see often, and we would begin to rethink how we felt about them from then onward. Hearing Radar write to his family and express his fears and concerns turns his previously silly version of caution into something more wholesome; we sympathize with him even more. Apply this logic to each character that we got to hear from in such a way, and you have an ongoing sub-series that everyone looked forward to each season.

So, we got to hear from these characters, but who are these characters? Well, they’re military stereotypes that are turned into some of television’s most likeable people as the show went on. Alan Alda’s Hawkeye, Loretta Swit’s Hot Lips, Jamie Farr’s Klinger, and William Christopher’s Father Mulcahy were the only four characters to stay on the entire duration of the show; furthermore, Hawkeye and Hot Lips are the only two full time characters that were always mains (Klinger and Mulcahy were supporting roles that became a part of the leading group). I’ll get into the rest of the characters soon, but the common ground is that all of these people are medical experts found within a military base during the Korean War. The title M*A*S*H means mobile army surgical hospital, and so that meant that the series could get away with two of the most successful kinds of stories in TV (war and medical shows); toss comedy into the mix, and you have a winning formula.

In the same way that M*A*S*H kept evolving, it also faced a whole slew of performers that came and went through its revolving doors. The only character to disappear because an actor wanted to leave suddenly was Trapper, once Wayne Rogers felt like he was playing second fiddle to Alan Alda; his departure from the show was written in rather decently, with Hawkeye’s clear discomfort that Trapper left without even saying goodbye. Otherwise, other characters left or were introduced more gracefully, and M*A*S*H often worked in twos (for instance, Mike Farrell popped in as B. J. Hunnicutt to become Hawkeye’s next best friend). Major Burns leaves after the love of his life Hot Lips moves on without him (likely to return to a wife that hates him), and Major Winchester took his place. Radar wasn’t replaced, since he was in the series for nearly eight full seasons, and someone that special just can’t be swapped.

The only other example is when Colonel Potter came in for Colonel Blake’s position, but the latter was the result of one of M*A*S*H’s first major risks. As early as the season three finale, the series was able to remind viewers that anything can happen during war. Blake was due to go home, and we’ve seen this song and dance before. A character would be on the verge of leaving, only to come back unrealistically. Many shows of the ‘70s are guilty of this kind of teasing, but M*A*S*H called their bluffs in this specific episode. As Blake was discharged, his plane was gunned down and he didn’t survive. Of course, actor McLean Stevenson was wanting to finish his time on the show, but the opportunity was there. M*A*S*H dared to go where many other sitcoms wouldn’t: the unraveled ending without much to sing about.

Because of the ebb and flow of characters, promotion of supporting roles, and shifting heads (Alan Alda would go from main star to a primary writer, and even director, throughout the series), as well as the numerous one-off episodes that tried something new each time, M*A*S*H was actually fresh for its entire duration. It ran for eleven seasons. Eleven. Seasons. Two hundred and fifty six episodes of pure quality, Sure, some episodes weren’t quite as good as the rest, but not a single notable misfire existed this entire time. What’s worth noting is that there was a clear effort to make sure that the series didn’t go downhill, with all of the transformations of lineups, tones, and creative decisions. Still, the show was uniformly M*A*S*H, and no other show was like it.

Of course, all good things have to come to an end (or they should), and M*A*S*H’s eleventh season was (somewhat) its shortest. Just sixteen episodes (in a series that averaged around twenty five per season for most of its run), and most of them took place in darkness (as opposed to the bright daytime focuses of the rest of the series). This was clearly the final hour, and darkness would envelop all. In war, you lose sanity, faith, or even your life. Everyone faced the darkness at some point. The jokes were still there, but M*A*S*H was at its most serious by this time. Its final episode “As Time Goes By” was a look at a time capsule of every character and significant moment of the series, and everything was set to conclude nicely.

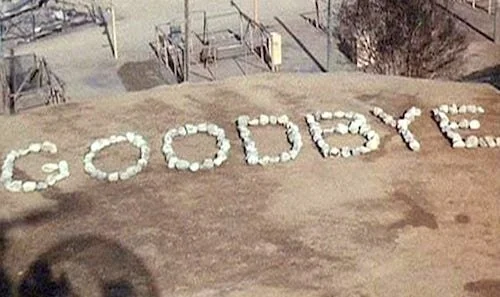

However, we all know that isn’t actually the ending (despite being the last episode filmed). No. That conclusion was “Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen”: a two hour opus of television that contained everything M*A*S*H did best within its runtime. Television writers like Damon Lindelof have chased the ecstasy and devastation of this series finale (he would succeed with The Leftovers), so the bar of how shows conclude has been raised continuously since, but “Goodbye, Farewell, and Amen” is the reason why perfect series finales exist. It was the first to be this brilliant. It ambitiously boasted a handful of writers that had to make sure that this eleven season behemoth was sent off perfectly. This was beyond an adaptation of a film adaptation of a book at this point. This was much more than a comedy to lighten up with. Death was discussed frequently. Hell was compared favourably to war (hell doesn’t claim the innocent). The escapism of the show’s silliness became coping mechanisms to survive trauma. M*A*S*H was untouchable, and it had to end on its biggest bang.

The first part is Hawkeye in a hospital, coping after a disastrous experience; in one of the series’ most daring decisions, his memories are disguised by hallucinations to help him forget the atrocities of the worst moments of his life (a mother killing her infant child in order to silence its cries so the enemy couldn’t find their location). Meanwhile, everyone else at camp was being changed in their own ways, as the Korean War’s final way of affecting its players. Winchester’s obsession with classical music has been destroyed by the sudden slaughtering of Chinese musicians that previously tried to bond with him (he can no longer hear it the same). Father Mulcahy — previously the voice of God for the people, and a listening ear for the sick — has been deafened by the noises of war. Hot Lips finally makes up her mind about her future: she will end up in an American hospital to help people this way. Klinger, who has done everything in his power to be discharged for supposed insanity, is now the only M*A*S*H member to actually stay behind willingly, as he is getting married to a local Korean woman. Hunnicutt is able to leave early, only to be sent back and miss his daughter’s birthday.

The war itself was about to experience a change: it would finally come to a resolution. The Korean War was finally over. Oddly enough, the actual war was only three years, meaning that M*A*S*H was at least over three times as long (of course, it was speaking on behalf of many wars, but still). Despite being given one last blindside, each M*A*S*H character was spared of their own personal deaths and could go home. We get to hear from as many people from the camp as possible, with what they wish to do post war; we even hear from a series of characters that we may have barely gotten a chance to meet. Every role matters here. Then, we get each different escape, ranging from buses, cycles, helicopters, and everything in between. We’re left with the tear inducing note that BJ Hunnicutt left Hawkeye to see: “goodbye” spelled out in stones, ready for him to see from a bird’s eye (fitting) view.

M*A*S*H was as progressive as television could have been back then. Outside of a handful of things that haven’t aged too well (Spearchucker didn’t last too long on TV for unknown reasons [but the kind of satire surrounding his character wouldn’t have worked well on TV and would be received poorly now], and Klinger’s wearing of dresses was for reasons of “insanity”, which isn’t as forward thinking as people may lead you to believe), the show is otherwise timeless. Whether you had an episode that was as sad as it was hilarious, or an entire episode based on dreams (and some great, cinematic ones at that), you just never knew exactly where you stood with M*A*S*H. You expected the comfort of an episodic series, but you knew that there could be a wonderful surprise around the corner at any time. For eleven years, M*A*S*H was breathtaking television, especially within the comedy category.

Of course, the great test of how television can run its course was best represented by M*A*S*H’s one follow up spinoff AfterMASH, which is — quite frankly — pointless in comparison. Because American television didn’t know when to call it quits, they got Colonel Potter, Father Mulcahy and Klinger into a veteran’s hospital. It would last for only two seasons. It was decent at best, but an indication that absolutely anything can be a beaten dead horse. It took over eleven years (if you take the original MASH book and M*A*S*H film into consideration as well) for this brilliant idea to overstay its welcome, but here we are. The Radar spinoff W*A*L*T*E*R wasn’t even picked up, and its existence was shorter than the time it took me to type its name.

However, I don’t look at these attempts as the aftermaths of M*A*S*H. I see the forever changed television industry as the epilogue to one of TV’s finest series. Shows could comfortably get darker. Not every comedy needed a laugh track. Shows must close as well as they begin (or even better). The respect of the patient, devoted viewer should always be considered. M*A*S*H didn’t see each episode as a win, but rather the bigger picture and what a television legacy could be. In many ways, the show could have failed. It was an adaptation (of an adaptation) that could have been compared unfavourably. It lost a lot of cast and crew members, and replacements were made. It tried to be serious within comedy, and funny within tragedy (especially during a time when television kept both worlds apart). It would end up being one of the longest shows in history at the time. It took many huge risks, especially with its one-off episodes. Not once did M*A*S*H fail. It is actually miraculous how great M*A*S*H is. Even if not every single episode is a masterpiece, I can’t think of a single episode I’d dread seeing ever again. Besides, it’s the overall achievement that carries each and every little episode, no matter how conventional some of them may have been. All things considered, M*A*S*H is unquestionably one of the greatest sitcoms of all time, and its countless achievements still resonate to this day.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.