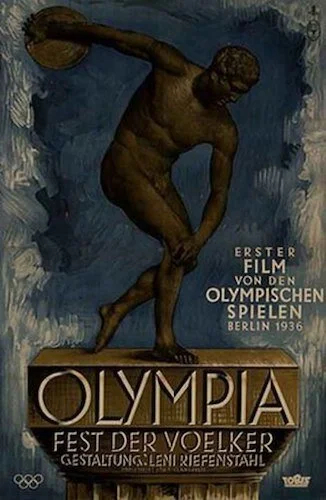

Olympia: Parts I & II

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

It’s Tokyo Olympics time, so we’re getting a little into the season here at Films Fatale. Each weekday will involve a film relating to the Olympics in any way. They can be sports films or other genres, and real or fictitious.

One of the most… sorry, let’s restart this. Two of the most challenging films to discuss in the history of cinema are Leni Riefenstahl’s masterpieces within the Olympia series. She was commissioned by the Nazi Party after her artistically powerful (yet narratively derivative) debut The Blue Light to make propaganda works. After the purely Nazi film Triumph of the Will, Riefenstahl was then asked to showcase the Berlin Olympics of 1936 as well as possible: it was her mission to make Germany look as great as she could. Well, she went above and beyond with both Olympia films, which transcend any form of easy decrying because of how innovative and exquisite they are. Have you ever watched sports on television? Well, Olympia changed your experience. What about slow motion and reverse shots? Well, Olympia was important with those effects as well. For the most part, almost any form of documentation of life ever since is indebted to these two brilliant works of art, despite their initial intentions.

So, in what ways did Riefenstahl try to make the Berlin Olympics the greatest cinematic event ever? Well, she began by preluding both parts (Festival of Nations and Festival of Beauty) with orchestrated depictions of athleticism with incredible cinematography, heightened mythological imagery, and the ambition of all of the greatest filmmakers of the ‘30s (the main difference here is that Riefenstahl was capturing life instead of stories). Beginning these two works in such a way works as an incredible appetizer for the main course. You see moving statues compete in Olympic related activities, and you can feel how monumental these ceremonies are. If anything, these introductions could replace almost any opening ceremony theatrics of the time (and for numerous decades afterwards) because of their sheer power. Before we even see the games, we have masterful filmmaking one cannot ignore. Riefenstahl had an eye for art over story; once provided with a narrative (life), she could let loose and become one of the greats.

The artistic opening sequences for both Olympia films are highlights of the entire project.

So, let’s get to the capturing of the actual Berlin Olympics now, and why Olympia is as brilliant as its legacy has dictated. Riefenstahl did everything in her power to make these games look good, including working with the best camera technology, creating her own photographical tricks, and ensuring that every event was treated with the same sincerity as the last. Therefore, so much history is found here, shot as well as it could be. Jesse Owens going against the odds to become the greatest runner of his time (of whom is photographed just as nicely as anyone else in this film, despite the rampant racism of the time). As many gold medal earning athletes — German or not — are also collected here, with love for all. Of course, Riefenstahl does provide at least a little bit of favouritism towards Germany (this was a propaganda piece, after all), but there is an emphasis on the love of filmmaking over anything else, which helps ease the pain of the obvious just a little bit.

In between the recordings of athletes giving their all, and the well edited pacing of these moments in both films, are slight glimpses of the kinds of idiosyncrasies that only life could provide you. One of the most haunting moments of any film of the ‘30s is seeing Adolf Hitler himself watching the games like any other spectator, only to see him scowl when a German sprinter drops a baton during a relay race (the Germans were leading until this mistake). History books can only teach you so much about individuals: documentaries like this detail these figures with even the smallest of flourishes; this includes the worst monsters of all time. What is initially shot with love now feels like the framing of discomfort. It’s this kind of content that makes Olympia still difficult to justify completely, despite its importance.

The sporting events in Olympia are shot nearly as gorgeously as the artistic openings.

Otherwise, there’s zero thinking involved to watch either Olympia film. You can cut to whatever event you want to see, or sit through hours of every sport and let the Olympics take you in. Not a single moment here is dull. No second is wasted. Even if you place both films back-to-back and watch for the entire near-four-hour duration, you’re graced with the ultimate versions of sports cinema of the ‘30s (and perhaps of all time). There really isn’t much more to say than that. You have the Olympic games, and an incredible director tasked with filming them. Voila: two of cinema’s most influential works ever. Again, it’s nearly impossible to reflect on any of the works of Leni Riefenstahl without reflecting on her association with the Nazi party, especially since the majority of her works are attached to their propaganda. This is why Olympia is tricky to bring up. The films themselves need very little introduction to know why they’re perfect as art and documentaries. Thus most of the discussions are spent on the troubling nature of the project and their inventive-yet-problematic director. Still, as films alone — ones that house life, sports, and celebration — both Olympia works are some of the finest you may ever see. They’re certainly ones to thank when it comes to, well, just about anything you’ve seen ever since.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.