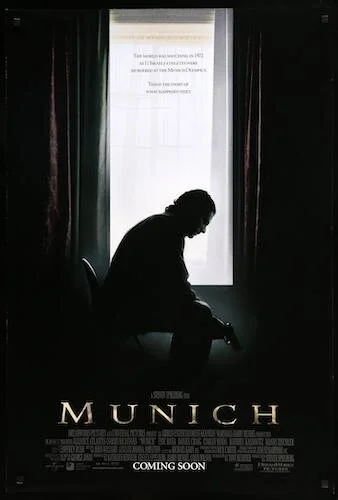

Munich

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

It’s no secret that Steven Spielberg’s Munich has been one of his more polarizing works: either crowned a finer film of the new millennium by the Hollywood legend, or as a distasteful use of real events as the source of what is ultimately a thriller (there are also naysayers of the occasional risks Spielberg takes here, while I’m sitting here thinking that I’m glad that he took risks at all). Based on the actual murders of Israeli Olympians by the terrorist group Black September during the Munich Olympic Games, Munich takes a bit of a revisionist approach at what could have happened after the fact: redemption in only the kind of ways that Spielberg can conjure up. Two things are conveyed in this picture, from what I can tell. Firstly, the then-fresh fears of the terror attacks of 9/11 that the world was still recovering from. Then, there’s the banding-together on a global scale that you can find at the Olympics, in a way that surpasses the competition of countries through sports: Jewish volunteers for an assassination on the terrorists responsible for the Black September killings come from all over the world.

At the centre of it all is agent Avner Kaufman, played by Eric Bana who was still at the height of his career (and arguably at his very best here). He is the vantage point of the responses to the atrocities of terror, the life of an agent that most of us could never lead, and a leader facing the pressure. Bana doesn’t go full-on action hero, which is a nice decision, given how easy that could have been. It’s the kind of element that prevents Munich from going overboard Hollywood in an insensitive sort of way. Instead, it just hovers around Spielberg’s usual comfort zone, outside of the occasional gamble (some of the kinds of action you see, as well as that sex scene that feels like Spielberg’s last major leap as a filmmaker). Even though Munich can feel a little glitzy, it doesn’t quite feel like Spielberg at his most lukewarm. There’s enough edge, creativity, and rawness.

Munich is typical Spielberg, but with just enough risks.

The end result is an intense, slow brooding — albeit polished Hollywood style — thriller, built on the angers of innocent civilians tired of the politics and beliefs that result in mass murders (no matter what era). The film is cathartic to a degree, and bold otherwise. If anything, the handful of dares here are the most New Hollywood Spielberg felt in years at the point of Munich’s release. It’s no wonder why the film had its supporters, despite the viewers that absolutely hated it. Even now, I’d argue it’s possibly Spielberg’s best film since we entered this new century (or at least there is a strong case that it could be), and one of the last moments before the filmmaker would succumb to his signature style for good.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.