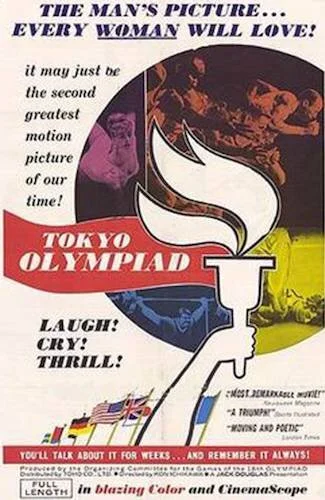

Tokyo Olympiad

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

It’s Tokyo Olympics time, so we’re getting a little into the season here at Films Fatale. Each weekday will involve a film relating to the Olympics in any way. They can be sports films or other genres, and real or fictitious.

I’ve been reviewing an Olympics related film each workday of the Tokyo Olympiad of 2020 (or 2021). I was intending on finishing with this specific documentary, for very obvious reasons. Firstly, there is the connection. Close to sixty years ago, Kon Ichikawa’s documentary was released one year after the 1964 Summer Olympics. He was tasked with representing Japan as best as he could. His story mirrors Leni Riefenstahl’s a little bit when she was commissioned to make both Olympia films. However, she revolutionized cinema forever with her two groundbreaking films. Thirty odd years after this achievement, only so much could be achieved. There had been a handful of Olympics since, and the art of film was forever improving (it still is). What could Ichikawa do?

Well, that’s another reason why Tokyo Olympiad was a must to cover. Ichikawa plays within the rules of film with this documentary, but he succeeds in every single way. Similar to Olympia, Tokyo Olympiad is a flawless depiction of the triumph of sports, particularly at these exciting games. However, the main difference are the artistic objectives of both films. Riefenstahl tried to push film by showing Germany in a positive, technologically-enhanced light. Ichikawa knew that the humans themselves would suffice. Only the best athletes make it to the Olympics, and he was aware of this. The subjects were enough to make the film worthwhile. So, let’s show them as best as we can, shall we? As a result, Tokyo Olympiad is an epic scaled look at the miracles of the human body, and the accomplishments of pure athleticism.

Humans are framed as the complex machines that they are in Tokyo Olympiad.

Additionally, the celebration of humanity banding together in these sports was the real focal point. Riefenstahl tried to highlight who won each event in her film, but Ichikawa wanted to capture the spark amidst the crowds, competitors, and juries that you can’t find anywhere else. He wanted to transmit the infectious aura of these Olympics, and his encapsulation of this chemistry leaps off of the screen. Every event feels thrilling, even if your desired athlete or team didn’t win. For three hours, Tokyo Olympiad is a pure sensation of excitement, glory, and ambition. If you were to block out every nation competing and somehow watch as an unbiased audience member, you’d still leave the film feeling like you’ve won many times.

The cinematography is sensational, here. While it doesn’t reinvent the wheel, the photography in Tokyo Olympiad is exactly as colourful, well framed, intriguingly lit, and close as it needs to be. This is true in every single instance. It feels like you’re watching living photographs of Kodak moments in between the best vantage point perspective of seemingly live events. Tokyo Olympiad is cinematically heightened and gorgeous to experience. It’s the kind of film that demands to be seen on the big screen. Despite what I’ve said about the film not pushing ground, there’s an interesting paradox here. Riefenstahl paved a path cinematically with Olympia, but it’s clearly a work of the ‘30s. Tokyo Olympiad still feels timeless, and that’s where it becomes an experience that’s impossible to describe. None of these athletes are currently competing, and the filmic grain is clearly of yesteryear, yet you feel like this is as fresh of a take as you can get. This is a nice confusion to have: how is a filmmaker capable of achieving this impossibility?

Tokyo Olympiad feels as fresh as it did upon its release.

Of course, it would make sense that a film about the Olympics should be a great sports film, but Tokyo Olympiad feels like a generation of the wind that athletes catch. It’s an indescribable sensation that surpasses most sports films — documentary or feature — ever made. Even people who, let’s say, despise sports would find something in Tokyo Olympiad that makes them feel better: like they want to achieve more, and experience the utmost triumphs. Kon Ichikawa was meant to record the Olympics: instead he documented life in all of its various capacities. All walks of life are participating here, and the exhilaration of being alive is just as present as the countless audience members and athletes. Tokyo Olympiad is a true spectacle of documentary filmmaking, and of cinema and sports as well.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.