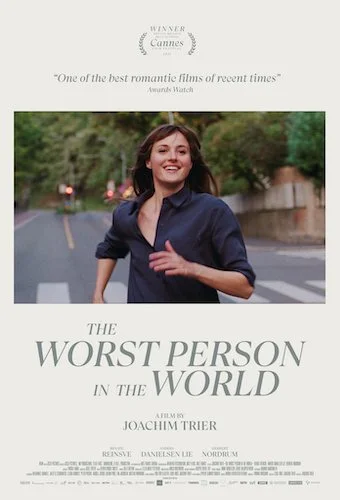

The Worst Person in the World

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

You’ve likely seen The Worst Person in the World making its promotional rounds, especially with the Academy Awards around the corner (the film is on the shortlist for Best International Feature Film nominees). This is actually the high that the film is riding after it was featured on — and topped — many best-of lists for 2021. It’s easy to see why Joachim Trier’s latest film (the final part of his Oslo Trilogy) has made such a splash with audiences and critics lately: it’s just so nice to have a romantic comedy (drama) that is this good again. As we are in the mind of Julie — a Jill of all trades, we learn — and are experiencing her numerous romantic shifts, we know what it is like to require change, but also take on a weight of guilt for hurting others (as well as herself). The film feels fresh as well, especially because it embraces a world post #MeToo (something The Worst Person in the World actually acknowledges, too), and so you can tell right off the bat that Trier is thinking in the present; how is Julie being portrayed; how is sexual exploration shot; are any backwards mentalities at the forefront?

While I’m looking back, I thought of one film quite heavily during The Worst Person in the World: Woody Allen’s Annie Hall. There aren’t any real story similarities, outside of the regrets and yearning posed in both works. Rather it is the series of postmodern excursions that made me reflect. This includes a sequence where nearly everyone else on Earth freezes in time, and a psychedelic freak-out (with hand-drawn animations and all); there aren’t nearly as many of these in The Worst Person in the World as there are in Annie Hall, but they’re strong enough to stand out similarly. Furthermore, the division of the story into chapters (prologue and epilogue included) felt Allen-esque, given the titles, mainly. In short, if I’m bringing up one of Woody Allen’s magnum opuses when discussing this just-released film, that means big things for the latter.

Renate Reinsve is phenomenal at the film’s epicentre.

Tethering all of these different viewpoints and sequences together is Renate Reinsve with a brilliant performance (certainly one of the finest of 2021), who is equal parts funny, gripping, sympathetic, and a tabula rasa for any of us that have made bad decisions in a relationship or have experienced heartbreak or the loss of a spark (so most people ever). It’s no wonder how she won the Best Actress award at Cannes last year: this film could not work with such a multifaceted and textured performance to hold it all in place. While we follow Reinsve’s Julie, we are still at a distance, despite moments that feel like she is talking with us (not in a literal sense, but the connection between us and her feels mightily close); it’s a strange dichotomy where we feel invasive yet unable to step in and help. It’s a great milieu created by Reinsve, and it really is the epicentre of the film.

Around her are similarly strong performances, dismal atmospheres, hilarious awkwardness, and the kinds of idiosyncrasies that you can only find in the twenty first century (the curses of cancel culture, the turnaround of blog and social media posting, and even — gasp — a small amount of COVID-19 details towards the end of the film). We feel a part of this whole journey. Now, what will The Worst Person in the World look like in the future? Years from now? Decades? Will it stymie itself as a capsule of its time? I think it won’t, given the universal and timeless depictions of the complications of love and not knowing what the heart wants. This is the key to The Worst Person in the World’s success as a whole: it has the rom-com figured out entirely, in the sense that it hasn’t gotten love figured out at all (are any of us clued in on love, really?).

The handful of fantasy sequences peppered throughout the film are immediately unforgetable.

Within seconds of finishing, I knew The Worst Person in the World was unforgettable and worthy of revisiting again. In a genre where fatigue is kind of commonplace, The Worst Person in the World instantly felt unique and worthy of many discussions relating to romcoms, dramedies, 2021 films, and, well, the decade so far. It’s the kind of work where I can actually sense that it can only age better with time, once we have allowed it to dictate how we feel about our own relationships and uncertainties in life (at least even for a little while). We will feel the need to revisit the film, and find a place within it since it understands us better than we know ourselves. It’s impossible to completely reinvent the wheel when it comes to romantic films, especially since love is one of the most over discussed topics in any form of entertainment. However, sometimes something can come around and at least introduce us to a side of an oversaturated theme and make us feel inspired again. That’s The Worst Person in the World: a major success of 2021 that is now able to strut its stuff for audiences to enjoy worldwide.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.