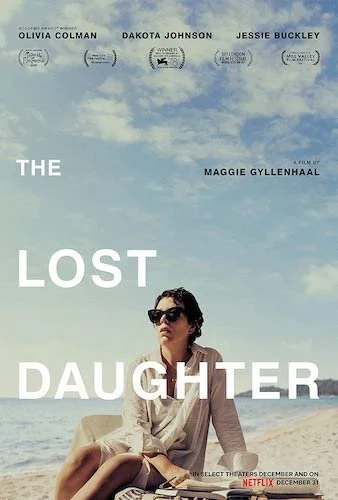

The Lost Daughter

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Between the two Gyllenhaal siblings, Maggie has always had a bit of a more quiet career; that shouldn’t mislead you into thinking that she hasn’t accomplished a lot. Her filmography boasts quite the opposite impression, actually, with fascinating role (The Honourable Woman) after fascinating role (Crazy Heart) after fascinating role (Stranger than Fiction), and I could keep going. Hopefully her name will shine greatly again with the release of her directorial debut: an adaptation of Elena Ferrante’s The Lost Daughter. This excursion to a Greek island is one full of air, allowing the beach-life and the sounds of nature to echo throughout each shot, transporting us to these locations. It’s only a single part of Gyllenhaal’s cinematic awareness that we see on display here, and her exhibition of her filmmaking skills are apparent enough that her recent nominations for her work behind the camera really make sense. Nonetheless, this ethereal tone is one you will pick up on right away, and it blends destination-based nostalgia, the faintest of memories, and the sickness in the stomach of the guilty and fearful really nicely.

I feel like this passive tone can slightly get in the way of the impact that a film like The Lost Daughter should carry, but it isn’t too distracting, especially since the film contains so many enticing moments. A professor’s vacation on an island is off to a rocky start, especially since she is not made to feel welcome right away. She, Leda, is traveling alone, and clearly with a lot of weight on her mind (this is conveyed extremely well by Olivia Coleman, who is as phenomenal as ever). The Lost Daughter eventually starts to unfurl one of its major tropes: continuous recollections of flashbacks. Here, Leda is played by Jessie Buckley, who is mind-bogglingly spot-on as a younger version of Coleman, and it’s the kind of attention to detail that is an art in and of itself. The two timelines converge quite obviously: here is a mother who regrets her initial days of being a maternal figure. This is reflected on the “present-day”, with brushes against other traveling families that our lead comes across, and her own way of coping with this feeling of loneliness (I’ll leave that to you to find).

The Lost Daughter is as heavy as it is sublime.

I’ve seen Damon Lindelof praise The Lost Daughter as the kind of achievement he strived for while working on The Leftovers, and I can see a few tonal and symbolic parallels: the original book’s connection to mythology (loosely inspired by Leda and the Swan, hence the main character’s name), an enhancement of the emptiness that voids in our lives bring, a focus on multiple perspectives via parallel storylines, the use of metaphorical objects used to the point of fixated obsession, et cetera. I feel like we may not get quite as full of a version of Leda’s life story here, rather just her connections to motherhood, so that to me is the major disconnection between Gyllenhaal’s debut and Lindelof’s series, but I still feel like the former is close enough with how emotionally impactful it can be. I will say that The Lost Daughter is the kind of film that I come across every once in a while: I appreciate it only so much upon the first watch, and my admiration for the same work grows over time. I’d like to see the film again, knowing what confessions I’ve heard before the bitter end, and experiencing the resolutions that Gyllenhaal dishes out. I can only report the initial viewing for now, and The Lost Daughter is a mysterious, saddening, sublime film that will either keep you guessing or keeled over with extreme hurt. It’s a strong start for Gyllenhaal as a director, and hopefully her ticket towards making more films; this can only be the beginning.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.