Noir November: In a Lonely Place

Written by Cameron Geiser

Every day for the month of November, Cameron Geiser is reviewing a noir film (classic or neo) for Noir November. Today covers Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place.

In a Lonely Place is a mystery Noir film that cleverly plays with audience expectations and goes against the grain when regarding Hollywood star Humphrey Bogart and his character, Dixon Steele. Having already consumed several of Bogart’s heavy hitting roles before seeing this film, namely Casablanca, The African Queen, and The Maltese Falcon, I had an image conjured up from these films of Bogart’s usual assets in acting. Somewhere in a low lit bar, Bogart’s playing a man beaten down by the world (or its expectations) resulting in sarcasm, a dry wit and usually with a drink in hand or nearby. He might play a cynic- but at his core the characters usually have good intentions. This film toys with that image and what we the audience may have come to expect from Bogart’s other hit films, granted, the film starts out in a very familiar place for Bogart as Steele, a washed up screenwriter with a chip on his shoulder and a drinking problem. After Steele throws a spiteful fist early on in the film however, we get an inkling that this incarnation of Bogey has more of a temper this time around. Steele is a far punchier lead than his roles in the previously mentioned films, and this only assists in the delightful second act flip, which I found to be particularly innovative for the time.

The film begins with Steele’s agent, Mel Lippman (Art Smith), a longtime friend and confidant, who just got Steele the opportunity to adapt a trashy pulp novel into a screenplay. Steele can’t bring himself to read the book even though he needs the work and instead hires a hat-check girl, Mildred Atkinson (Martha Stewart), who he heard loves the book and had just finished reading it. She comes to his place that evening and ecstatically goes over the plot while he glances at a new neighbor across the way who had also noticed him earlier as well. After Steele gets the general idea of the story, which he seems to detest a bit internally, he sends Ms. Atkinson home for the night by a nearby cab station- which he pays for in addition to helping him with the pulp fiction. Early the next morning Steele’s met by L.A. Detective, Brub Nicolai (Frank Lovejoy), who had served under him during the war. He brings Steele in for questioning, and while Steele believes it’s because he got into a fight with the son of the studio head the previous day, it’s actually because he’s the prime suspect in the murder of Mildren Atkinson found dead earlier in the dark hours of the morning.

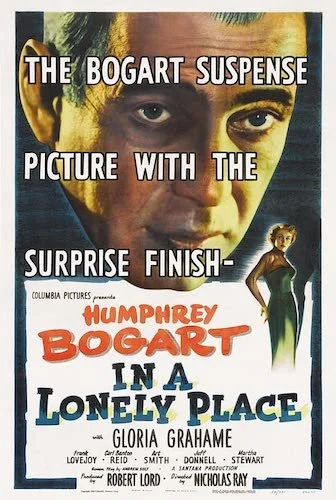

Gloria Grahame and Humphrey Bogart in In a Lonely Place.

Steele doesn’t do himself any favors when being questioned by the police. By his nature, he’s a macabre idealist with awful self-esteem, someone who’s intentionally vague and (as a writer does) likes to exaggerate from time to time. Luckily for him his new neighbor, Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame), did see Ms. Atkinson leave the previous night without Steele, providing him an alibi, as well as a flirtatious invitation. After a while the two begin to fall in love, they begin to date and Steele gets back to writing after Laurel helps get him off the bottle for some time. Though Laurel and Dixon do seem to be mutually affectionate to each other, things begin to go awry when an evening at the beach turns sour and Dixon’s temper reemerges when he discovers that Laurel was brought in for further questioning by the police chief, which she didn’t tell him

about as she didn’t want to interrupt his writing streak. Enraged that he’s still being followed amid uncertainty in the air of whether or not he actually did kill Ms. Atkinson, Dixon flies into a fury while on the road and almost kills a man after a traffic altercation.

This is when the film switches the perspective to that of Laurel, whose paranoia about Dixon grows slowly at first before he starts displaying seriously questionable behavior. This is the film’s best trick, they took great effort in the first half to assuage any suspicions of Dixon as a murderer and slowly inserted moments and scenes that could be looked back on with the latter half of the film’s perspective that turn the audience against Dixon whose losing control in his life and begins to break down the closer we get to the finale. It’s a very clever notion, the film’s twisty perspective and illusory truth pair to make this one a memorable outing for both Bogart and Grahame.

While this film may not reach the heights of the other Bogart films mentioned above, it does a fine job with some fun creative twists thrown in for good measure. There are some particularly entertaining pieces of the film that I must mention before departing however. Firstly, I really enjoyed the drunken theatrics of Steele’s has-been actor buddy, Charlie Waterman (Robert Warwick), who pops up throughout the film to espouse lyrical poetry and to support his screenwriter friend. Bogart also has a few really unexpectedly funny lines throughout as well, like when he jokingly suggests another suspect was the actual killer, not him. The man replies as Dixon shakes his hand on the way out: “What an imagination. That’s from writing movies.” And Dixon turns it around on him in a split-second with: “What a grip. That’s from counting money.” There’s a lot of sly jabs like that throughout the film. As for the downsides, the film definitely feels its age. Those turned off by depictions of toxic masculinity will probably not find much to like about Dixon Steele. Which is somewhat expected given the time period, but it’s still jarring at times and admittedly kind of fascinating to see the wheel of time rolling ever farther from cinema’s golden age of studio controlled dramas, musicals, and epics. If you’re looking for a decent black and white mystery noir, this should do just fine.

Cameron Geiser is an avid consumer of films and books about filmmakers. He'll watch any film at least once, and can usually be spotted at the annual Traverse City Film Festival in Northern Michigan. He also writes about film over at www.spacecortezwrites.com.