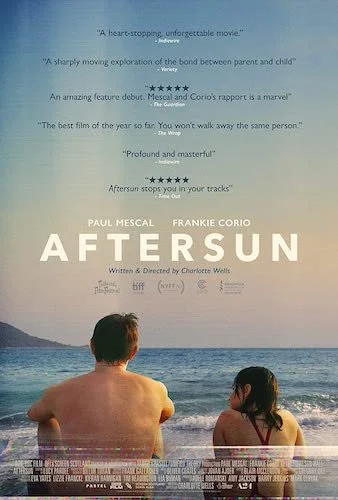

Aftersun

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: this review contains major spoilers for Aftersun. Reader discretion is advised.

Very few films toy with the concept of memory in such minimally effective ways. Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love is about all of the writing on the wall before the inevitable love — and heartbreak — hits: it is a secret to be harboured on to for eternity. Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight divides a troubled life into chapters, each dominated only by specific moments of each phase of a person’s upbringing. Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation makes a reflection on an excursion feel like we are frozen in limbo and blissfully aimless. The other commonality these films share — outside of their dreamy, rich aesthetics — is that their impact was instantly felt. We just knew that these would be timeless works that would define a generation, our hearts as cinephiles, and the filmic medium. It’s no secret that Kar-wai, Jenkins, and Coppola are amongst the most beloved auteurs of their time (and even all time). It may be too early to say the same about newcomer Charlotte Wells, but what I can definitely confirm is that Aftersun, her feature debut, does share enough of that prompt wallop that the aforementioned works posses. Especially during a time where film hasn’t really been as consistent as one would have liked after the height of the very pandemic that stalled the industry, Aftersun stands out as an instant classic of indie cinema (to me, anyway).

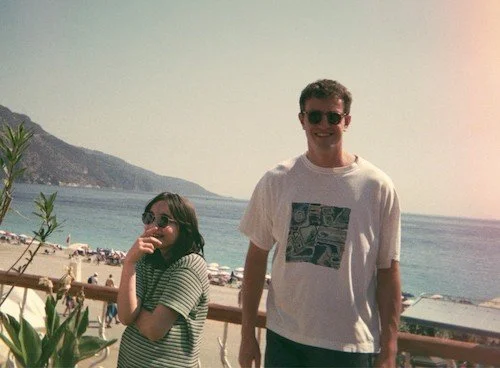

Based partially on autobiographical elements, Wells’ Aftersun does exactly what it needs to with a tiny cast (led by the stellar rising star Paul Mescal, as father Calum Peterson, and the brand new scene stealer Frankie Corio as daughter Sophie), limited locations, and a super short one hundred minute runtime (it does not need to be a part of that three hour crowd that many of 2022’s awards season films feel the need to be). Wells tells the story of a broken family (the mother is never seen in the film, but she is the primary guardian of Sophie) and a father that wants to win his daughter back via a getaway vacation to Turkey. The timing couldn’t be better: the late ‘90s. It’s when I was a child as well (slightly younger than what Sophie was in this film) and similarly didn’t know of life’s hardships when I was on vacation. It was the end of the easy-spending, lavish eras of life; before the 2008 housing crisis; before umpteen amounts of recessions; before countless industries would fold and many dreams would be shattered. Here, father Calum is a sign of things to come as he tries to provide the best trip for Sophie despite being clearly strapped for cash.

The way Aftersun plays around with time is extremely precise and highly effective.

Calum tries his best to bond with Sophie, who is quite acute for her age. She picks up quickly on the fact that her father is trying his best to get by, whether it’s noticing the all-inclusive bracelets the other youths around her have on their wrists or how upset her father pretends not to be when she loses his expensive scuba mask. Despite all of this, Sophie thinks she’s catching on to everything, and she is very bright already, but she has yet to learn about the feeling of suffocation that people feel when they cannot make ends meet in life. See, it takes a complete watch of Aftersun for the entire film to click. The film starts with the sounds of a handycam whirring, and then we see recorded footage of the end of this trip to Turkey before the cassette inside of the camera is rewound to the start. Then the film begins. It’s important to know that this feature is actually told almost entirely through hindsight, and that perspective is that of Sophie, now the age of her father during the trip, realizing that life never was as simple as it once seemed. She didn’t have it figured out. She still doesn’t. None of us ever will.

Dive deeper into this notion and you will find that there is more. The title of the film is based on after sun lotion (Wells cleverly condenses the two words into one, representing more of a thought and idea than a very literal symbol that feels too on-the-nose), which is applied on sunburns. You can take this very literally, seeing how the Patersons are spending all day outside and under the hot Turkish sun during this vacation, but I don’t think this is quite the full extent of what the title represents. To me, this is Sophie consoling herself after the biggest burn she ever received: this trip. She bonds with her dad (even if apprehensively), starts to blossom as a tween (discovers her first crush, breaks out of her comfort zones, and even starts to understand her father via what brings him joy), only for the excruciating final shot to hit us: she never saw him again after this trip.

Yes. The last time she sees him and shares an actual experience with him is at the airport, and we’re now on the opposite end of the footage the film starts off with (bringing this recording full circle), as Calum leaves Sophie for good; there’s a brilliant overlaying of the sounds from the previous scene, where Sophie’s own baby is murmuring. How can a parent abandon a child and/or not be present in their life? It is heavily implied throughout the film that Callum has suicidal tendencies, and maybe this trip was a final farewell to a loved one for him; whether this is the case or he created a new life for himself to survive, Sophie is watching these tapes again both with yearning and pain. Then again, she does have access to his camera and recording, so there was clearly some connection since the trip. It could have been from the postcard that Calum already wrote while still in Turkey for Sophie, clearly dead set on whatever decision he was to make (and quite torn up about it, as he breaks down in his hotel room alone). Either way, this was the end of her relationship with her father for good.

Aftersun is a bittersweet film until the very last shot, where it is apparent that the film is actually quite tragic as a whole.

Wells has so many great ideas for her first feature, and it would take a full on thesis to go through all of them, but I will point out at least a couple of my favourites. As much as I am a David Bowie fan (I consider him the greatest solo male performer in contemporary music history), I have never been into his collaboration with Queen (“Under Pressure”), and that song worked its way into the climactic sequence of Aftersun. What Wells does here is use the viral isolated vocal tracks that made their rounds on YouTube a few years ago (or the idea, anyway) and places them above Oliver Coates’ stunning score (which deserves its own shoutout: it’s gorgeously bleak in a Brian Eno way). As the rest of Queen’s music fades out, we’re left with just the words that now sound like a cry for help amidst a father-daughter dance underneath pulsating strobe lights. One of history’s most overplayed songs now has new life, and it’s in the form of the exact point that a father knew this would be the last core memory he shared with his child. There are no more words I can even say about this. It left me speechless.

On that note, there are quite a few songs to place you in the era and place (a ‘90s summer vacation spot), including Bran Van 3000’s “Drinking in L.A.” (that song still slays), Chumbawumba’s “Tubthumping” (this song, not so much), and an adorably awful karaoke version of R.E.M.’s “Losing My Religion” by Corio (but she did better than I could do on the spot, and it’s a tenderly vulnerable moment that works as yet another vivid snapshot of what felt like better times). Despite the obviousness of some of these tracks, not once did I feel like Wells was being lazy and relying on nostalgia to get us invested. This is her nostalgia, and she incorporates all of these songs quite seamlessly, never forcing me out of the experience to gawk upon her music selection. She does the same with what we see as well, ranging from 90s arcade games to fashion. It’s not quite as big of a time capsule as, say, In the Mood for Love, but it also doesn’t need to be. We’re connected enough in Aftersun to feel like we are a part of a history, a daydream, and a memory, all amalgamated into one blur of pondering: why did this happen to Sophie? Could anything have changed to keep her father around? Was this always how it was going to be? Was the trip always meant to be a final farewell? We’ll never know, but it doesn’t matter anyway.

Aftersun beautifully represents soul searching via a nostalgic daydream to see where it all went wrong, and its lack of concrete answers proves that hurt doesn’t always need a reason to happen.

We’ve come to the end of 2022, and for the first time I feel certain in saying that this film, Aftersun, is the greatest film of the decade so far. Before, I would just go with whatever I had ranked the highest, and I would be left wondering if these films would pan out in the way that I felt like they would through the courses of time. Aftersun is one of the rare times I know right away how I feel about it, and that I am sure I haven’t seen anything like it before; not in 2022, not in the 2020’s, perhaps never before. How this wasn’t recognized by the Golden Globes but Elvis and Avatar: The Way of Water were almost feels sacrilegious to me. We have a breathtakingly aching film here, a masterful debut from a promising filmmaker, and a work of art that already feels singular. There’s a reason why this humble little film is getting placed on so many best-of lists even if the larger academies are ignoring it: because its impact is felt, even if the film isn’t playing the awards season promotional game. It doesn’t need to. Awards, shmawards. I’d like to be wrong, because Aftersun deserves everything (and more), but time will prove that this film is as brilliant as I know it is in the present. Watch. Aftersun will be discussed in classrooms in the future, and it may be considered in larger discussions as well. It will define 2020s cinema.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.