Drive My Car

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

During the awards season, I will be covering films that are a part of the discussion that have been out for a while.

The journey that Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s latest film Drive My Car has taken is an astronomical one. I recall when it was the latest international feature at the local movie houses, but we do get a ton of those annually. However, this film made a bigger splash. It picked up a few smaller film awards, as is common for good flicks, but its climb up to the cinematic heavens just continued to escalate. It became the film to beat for all of the international film categories, shutting out a lot of other previous contenders like Titane and Parallel Mothers. Eventually, it grew outside of these restrictive categories and became one of the most accoladed films of 2021. Yes. Drive My Car has this impact on viewers. One major reason why I feel like it has this reign is because of Hamaguchi’s stunning filmmaking capabilities. Whenever I bring up Drive My Car, many viewers have brought up the same response. The first hour of the film feels long. The second hour allows the film to pick up its pace. By the third hour, no one wanted the film to end.

I don’t feel quite the same way, as I think Drive My Car is hypnotic from the get-go. However, I feel like this is the foray into artistic filmmaking that the general public is experiencing maybe for the first time. There aren’t many arthouse or art-oriented pictures that resonate as deeply with audiences as Drive My Car does, especially with its three-hour scope. The one thing I agree with these viewers is that I, too, never wanted the film to end either. It could have been twelve hours and I wouldn’t have minded. When a film is beyond a story and a premise, it becomes life when handled properly. That’s Drive My Car: a poetic stroll past death, rebirth, and the corridors of time. It is a three-hour adaptation of a short story by Haruki Murakami that somehow never overstays its welcome. It never feels overlong. This itself feels like a miraculous achievement. Then, there’s the idiosyncratic nature of Drive My Car. We experience loss and rediscovery as the limbo of existential incubation that we all experience (perhaps on a daily basis): we cannot keep going, and yet we use our dread as a means of comfort and warmth (counterproductively). Drive My Car never holds our hand, but it consoles us, and this mutual understanding — between art and observer — is exactly why it is as beloved as it is. Now, it is a Best Picture nominee, and one of the most daring (and correct) nominations in recent years (perhaps ever).

Drive My Car represents ennui in such a cathartic way.

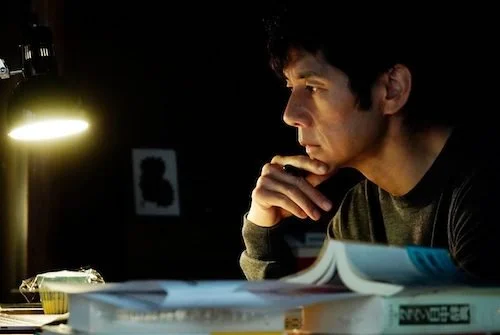

Yūsuke Kafuku has to face the biggest challenge of his life (which I don’t want to give away, despite the fact that it is kind of the basic premise of the film), and the first portion pre-title-screen (I recall it being about a half hour of runtime or so) acts as a prologue of what is to come. We see Kafuku’s like get established long enough that we then know what he is going through: life goes from completely purposeful to being one plagued with ennui and agony. As Kafuku begins a new project as a producer, and his cast and crew ask for his expertise while he is trying to piece his own life back together, we fall in love with the reconstruction as well as the deconstruction of our beings. What makes us in a spiritual way? As Drive My Car places a diaphanous light on us as living creatures as well as players of life, we see ourselves in Kafuku, as well as alongside him (like an out-of-body experience). Drive My Car feels ghostly, but it also ripples with pulses of existence.

As stoic as the film is, it never feels like a bore. Drive My Car moves at such an even, patient pace, like the titular vehicle being operated by someone else. We sit and watch life stroll past us at a low speed. At times, there is no driver at the wheel, and this is a car in neutral just carrying itself arbitrarily. Life doesn’t wait for us; it certainly wasn’t waiting for Kafuku. Despite everything that happens, not once did I feel death itself breathing down his neck, or this ominous presence. It’s as if Hamaguchi was capturing love in the stillest of moments, and it’s this kind of magic that makes the more powerful sequences really boom; it’s not like this spirit came from nowhere. I feel like it’s this underlying, authentic, angelic presence of Drive My Car that hits people at different times; some at the two hour mark; some earlier; I got hit as soon as this film began. Either way, no one will leave the picture not having felt this awakening: like discovering a closed off part of our heart that we have protected from the harms of the outside world and have finally tapped into again.

Drive My Car is both existential and poetically beautiful.

Despite all of this purposeful ambiguity, Drive My Car still goes the distance and showcases proper resolutions. It’s a picture that could have gone on forever, yes, but it still wraps up beautifully, and not in a way that stymies everything that came before it. It closes as organically as it exists. It begs to be experienced again instantly afterward. It’s impossible to shake the film off. It’s a rare motion picture that I felt like I was transported to and was living vicariously through the actual picture itself. It was experiencing my own hardships and emptinesses on the big screen, and you will likely feel the same way. No matter what our tribulations are, Drive My Car feels like a blank slate that consoles anyone that has ever grieved, ever hurt, and ever lost. There’s a lot of actual chauffeuring in the film, as well as the creation of lives via a production, so there are lives being passed around to exist vicariously anyway. With Drive My Car, Ryusuke Hamaguchi will allow you to use his picture as a vehicle to relive your eternalized history, and it’s the kind of catharsis that has made it one of the most unforgettable films of 2021. It is a rare epic that feels eloquent rather than ambitious, and it has to be seen to be felt and believed.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.