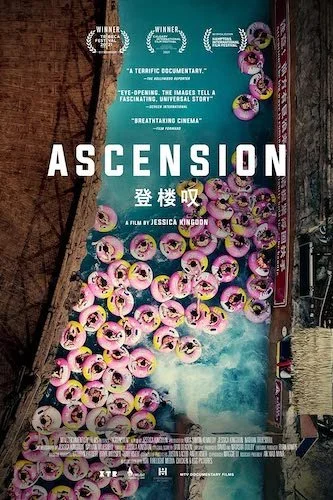

Ascension

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

During the awards season, I will be covering films that are a part of the discussion that have been out for a while.

The idea of a city symphony film (like Man with a Movie Camera, for instance) is to highlight the different appreciations for one’s homeland through the art of cinema. Ascension seems to be this kind of a motion picture once you start watching Jessica Kingdon’s documentary, but that actually couldn’t be further from the truth (even though she possesses a very artistic eye and can work a camera to love what subjects it captures, as everything here contains a certain filmic tenderness to it). Ascension is actually a highly political film that wants to showcase the working class as full of lovely souls that are squashed by capitalism. Their dreams of something more — promised by the rat race — are endless collisions into dead end jobs and dangled hopes. Their environments look awful: typically cold, gloomy, and mechanical dungeons that they are confined to for the upper classes to benefit above them. Ascension is a very dichotomous affair where you will be appreciating the art on the surface and hurting inside at the same time.

Even though there is very little dialogue and Ascension is full of static shots of things happening (factories operating, life passing by, souls being sucked out of hard working citizens), it never feels like a chore. Not once was I checking my watch. I was hypnotized, as if Kingdon was playing the part of a CEO with false promises of something greater than they can offer, and we have X-ray vision and can see right through it whilst being aware of the same artificial exterior at the same time. It operates a lot like a Ron Fricke feature where we temporarily live vicariously in the bodies of others, except here we’re not transported all around the world to experience different cultures. We’re in Chinese workplaces, but we can also recognize them as our own. We maybe weren’t working on sex dolls, but we have been hunched over working on something else. We’ve been there. We are here. Never before has our monotonous, dull life felt so beautiful.

Ascension places all of the working and lower class viewers into the film, letting us know that we are all visible across the globe.

And yet Kingdon never lies to us and insists that this is beautiful: it’s only shot that way. We’re fully aware of how awful this really is, and how our fellow person has become a piece of the large machine called the capitalist system: we’re told we can do well with our own hard work, yet our fates are determined by those higher up than us, so how far are we really getting? We’re told the same story throughout Ascension, and yet each and every new shot tells us something else. There’s even something very meta about seeing an employee working on fleshing out an adult humanoid toy, as if people are crafted just to make more money. That’s not what growing families see, but this is exactly what businesses hope for, in any economic situation: more staff for products and services to earn more revenue. You can apply this extent of depth to any of the carefully-assembled sequences in Jessica Kingdon’s Ascension, and it will be worthwhile, considering its images and messages will stick with you for a while (both for completely different reasons).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.