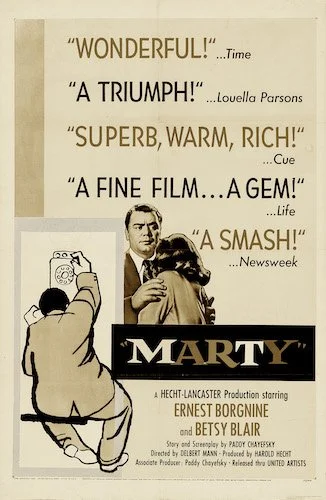

Marty

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Marty won the first Palme d’Or at the 1955 festival; all previous winners were deemed Grand Prix winners, and you can find them here.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Marcel Pagnol.

Jury: Marcel Achard, Juan Antonio, A. Dignimont, Jacques-Pierre Frogerais, Leopold Lindtberg, Anatole Litvak, Isa Miranda, Leonard Mosley, Jean Nery, Sergei Yutkevich.

When Cannes was vying for a change in direction in 1955, they rebranded their top prize that was once the Grand Prix; it was now the Palme d’Or, and would be for around ten festivals (it would revert back to the Grand Prix for a short while, and then back once more to the Palme d’Or permanently). The first winner of this new title was Delbert Mann’s Marty, and it felt serendipitous when it won, considering it was destined to become a Best Picture winner as well. What separates the Academy Awards from Cannes is that the former awards films of all kinds, whereas the latter honours creative, artistic, and technical breakthroughs in the medium that cannot be denied. That’s where Marty feels a bit contradictory. It is shot well enough, but it isn’t exactly a revolution photographically. It isn’t highly imaginative, as the story is one of the most straight forward of all the magnum opuses of the ‘50s. Marty is artistic to a degree, but it is hardly an art film. What makes Marty shine is just how powerful its love, cinematic-realism, and serious tones are.

Part of this revelation comes from Paddy Chayefsky: one of cinema’s finest screenwriters. He adapted his 1953 teleplay of the same name into this humble drama that barely cracks an hour and a half in length, and yet it possesses entire lifetimes. The titular Marty Piletti is someone you feel like you’ve gawked at for years, as he’s been confined to his butchery workplace — tethered by society’s inability to allow him to move up in life as a struggling lower-working-class citizen. He is played by Ernest Borgnine, who was often cast aside by Hollywood to play brutish or oafish characters. Here, he is a misunderstood man who just wants to be happy. We’ve all been there, Marty. We’ve all been there. Through Chayefsky’s humanistic writing and Borgnine’s ability to drill deeply into your heart, this main character and his simple escapades become the main events of your present, and nothing else will feel like it matters in this brief run time. Borgnine would go on to be beloved in a completely different way for the rest of his career: with warmth and through the life of his iconic smile.

Ernest Borgnine makes the character Marty feel like one of the most sympathetic protagonists of ‘50s American cinema.

Marty is bogged down not just by circumstances against his control, but by loved ones that mean well additionally. His mother — of whom he lives with — and aunt view Marty as unsuccessful, particularly because he hasn’t settled down and gotten married (whereas his siblings have already). The ways his family feel about them are one thing (the disappointment just drips off of the screen), but the couple of asides where you see how they feel about life are pure Chayefsky-an cynicism: a precursor to what you would eventually find in Network, where the writer went fully bold with his takes. The main premise of Marty otherwise is simple: the lad falls in love with teacher Clara who is also treated as an underwhelming member of the same society that never cared to help the struggling be a part of the race of the American Dream. This romance is combatted by outliers that keep wanting to meddle with both Marty and Clara’s existences: those who are deemed inferior can never be left to themselves, as holier-than-thou “winners” have to help the aimless. Marty tells a simple story, but with enough pent up annoyance by Chayefsky. He’s been looked down upon before. It’s time we heard a Hollywood story about someone that was just like us average folks. This feels tangible.

Even then, Marty isn’t explicitly a “Hollywood” picture through and through, but just enough that it reaches worldwide audiences without scaring way too many people. This relates to the ending of the picture as well, where we are left — nearly literally — waiting on the line to see what will turn out for poor Marty, who has had to face bad luck yet again in is thirty four year life of pure misery. Not this time. He’s going to turn things around (we hope). Marty provides us just enough hope to cleanse our heart, but we don’t actually know if we’re really heading in the right direction or not. We just have a glimpse of a prayer. That’s all we need. That’s all Marty himself needed. The film gets by on the little things, and I still can’t say that about most motion pictures since this was released. This was back in 1955. The conversations at the film’s core are heavy, but the bliss comes from the tiniest of ingredients instead of grandiose statements, and if that isn’t as anti-Hollywood as a Hollywood picture could get back in the ‘50s, I’m not sure what is.

Marty embroils itself with the deepest interpersonal conflicts within the lower-working-classes, but also with the little things that make life special.

So, no. Marty didn’t have the technical, artistic, or creative flair that many other Cannes favourites possess. But that’s why Marty is a special Palme d’Or winner, and such a curious first winner of the prize (particularly because Cannes was established by this point, even with the branding shift). Marty is exactly like the character it is named after. It is typical but special; cold yet warm'; rudimentary but profound; uncomplicated yet exemplary. It doesn’t need camera trickery, heavy metaphors, or intricacies to be good. It’s perfect in the most fundamental of ways, like many works before just missed out on how to make a fantastic film by using the most basic parts. Marty excels effortlessly, but this is all the trickery of Mann’s modest direction and Chayefsky’s multifaceted writing. Once again, this is just like the main character, who has been judged because of quick first impressions that completely miss the many layers that make Marty who he is as a person: far more fascinating than anyone was willing to see. Mann and Chayefsky saw it. Cannes saw it too. Eventually, even the Academy saw it. For nearly seventy years, we’ve been able to see Marty for what it is, and it is paradoxically singular for such a customary picture; it’s clear that its reputation won’t change at this point.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.