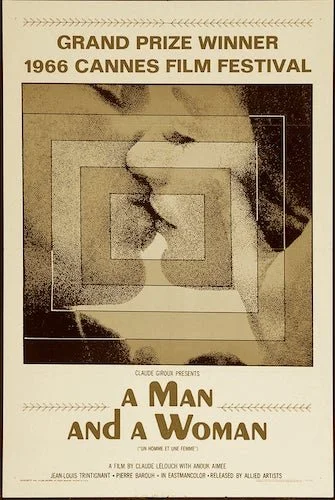

A Man and a Woman

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. A Man and a Woman won the twelfth Palme d’Or — temporarily reverted back to the Grand Prix — at the 1966 festival, which it shared with The Birds, the Bees and the Italians.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Sophia Loren.

Jury: Marcel Achard, Vinicius de Moraes, Tetsuro Furukaki, Maurice Genevoix, Jean Giono, Maurice Lehmann, Richard Lester, Denis Marion, André Maurois, Marcel Pagnol, Yuli Raizman, Armand Salacrou, Peter Ustinov.

Warning: the following review briefly discusses the triggering subject matter of suicide. Reader discretion is advised.

Claude Lelouch is a highly prolific filmmaker, yet A Man and a Woman is likely the sole film of his you know, particularly because of how greatly it took the world by storm upon release. It won the Palme d’Or (naturally, because I am covering it for my Palme d’Or Project), but it also made a big stink at the Academy Awards and Golden Globes back when it was a lot more difficult for non-English films to make a splash outside of the international categories. What is it about this romantic drama that worked so greatly with audiences outside of France? Maybe it was the slowly growing rise of French New Wave auteurs that seemed like they were too much for the general public; someone like Lelouch who didn’t make New Wave films but still possessed artistic flair felt like just enough of a deviation from the norm for the masses, especially because no rules feel broken here. A Man and a Woman is unique enough to matter, but not an overblown practice of experimentation that would feel off putting. I do wish it did more, but the little cinematic flourishes that are implemented are nice enough (especially when it comes to the editing of the picture).

In short, A Man and a Woman feature the obvious title characters falling in love, yet they have a lot of baggage to carry (particularly the fact that the both of them lost their previous spouses and are raising children alone). Anne’s husband died whilst working as a stuntman, and Jean-Louis’ wife killed herself after fearing he died during the 24 Hours of Le Mans (where a massive accident occurred). Both Anne and Jean-Louis find it difficult to move on, and the short duration of a film really doesn’t feel like enough time for broken people to heal and glue themselves together to feel whole again, but Lelouch is able to find a bit of storytelling magic to somehow make such a miracle of love work well enough. The film isn’t quite Hollywood in its approach, but someone like Lelouch definitely feels indebted to westernized filmmaking. Even in the ways he reflects back on the film set during the stuntman’s scenes, you can see how much Lelouch simply loves cinema. Some of that translates through A Man and a Woman. This is a romance film first and foremost, but it’s also a love letter to the medium Lelouch spends every waking hour devoted to.

A Man and a Woman is stylish enough to feel more interesting than basic.

Outside of these occasional filmic choices (snappy cuts, interesting angles, some aesthetic poetry here and there), A Man and a Woman is quite a humble and straight forward film. It doesn’t really envelop itself in the sadness or curiosity of a widow and widower trying to find love again, but you do feel the spark between these lost souls, and I think that’s the most important element necessary for such a story to work. In hindsight, it can’t compete with either the strongest New Wave or neorealist films, but it sort of feels like a nice bridge in between. Love has been tackled and re-approached again and again more than anything else in the history of storytelling, so something like A Man and a Woman won’t feel quite as inventive as some of the strongest examples one can think of; perhaps it seemed fresh enough back in 1966 for Cannes to feel like it was worth awarding. It’s still worthy of at least one watch, because the chemistry between Anne and Jean-Louis is quite indescribable (like those butterflies you feel when it all first starts), and that alone makes A Man and a Woman feel inspirational and real (to a degree).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.