Blowup

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

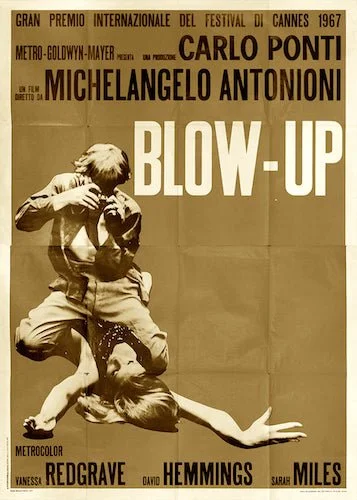

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Blowup won the thirteenth Palme d’Or — temporarily reverted back to the Grand Prix — at the 1967 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Alessandro Blasetti.

Vice President: Georges Lourau.

Jury: Sergei Bondarchuk, René Bonnell, Jean-Louis Bory, Miklós Jancsó, Claude Lelouch, Shirley MacLaine, Vincente Minnelli, Georges Neveux, Gian Luigi Rondi, Ousmane Sembène.

Known for his long, still shots and patient directorial style, Michelangelo Antonioni was already revered by the time he was about to make his English language debut. After watching this postmodern, jazzy opus (which may be the best film he ever made, if not a strong contender for that title), it’s clear that Antonioni is an observer, hence his signature ways. While other filmmakers that tried to capture the Swinging Sixties missed the mark, Antonioni knew it took more than just a few interesting tricks and ideas to replicate the aimlessness that was going on (although he does break a number of rules himself). Blowup (or Blow-Up and Blow Up, depending on who you talk to) doesn’t invite you into the chaos of this loose time. Instead, it pushes you further and further away, so you are forced to look in from the outside and try to break into the randomness that takes place. You forge your own way into Blowup. That’s the secret: the freeness came from those who sought it out. Blowup is as freeform as filmmaking can be, only if you surge past its cemented artistry and make your own narrative.

Calling Blowup a series of vignettes feels a little dishonest, especially because the film is not as sliced-up as it may seem. It’s not about having a bunch of events happen to the main character (a young, hip photographer named Thomas). Blowup is interested in the lethargy of life even within the abnormal: a far more fitting depiction of one trying to be ingratiated within a cultural movement, only to find that it was all for nothing (can we really imagine that Antonioni was interested in the Swinging Sixties? No. He wanted to see what was truly going on within those that partook in this era). While Blowup isn’t a film about conformity (particularly because it was quite an experimentally told picture), it does hold some empathy for the audience that was likely wanting to watch this film: not the partying go-getters that you would find in Blowup, but the lost souls that have been dulled to existential death by their surroundings. We can attend a Yardbirds concert, gaze at a ménage-à-trois in the making, or even be roped in on a potential murder, but we are still there only spatially, and not invested. As the photographer that tries to capture these moments, we will forever be an observer of counterculture and not a member. There’s something quite profound in this.

Michelangelo Antonioni uses the metaphorical character of a photographer to place us at a distance from counter culture.

Antonioni loves to catch his viewers off guard once they are lulled into a cinematic trance by his passively-told pictures, and Blowup may be his most chaotically told feature. What is especially fascinating is that the film is told nearly solipsistically with Thomas representing the magnet that attracts all of the goings-on around him (it nearly feels impossible when you consider the amount of oddities that occur to him in such a short time period). It’s as if everything else doesn’t exist, and Thomas is all of us trying to partake in these occurrences to varying degrees. While other Antonioni films feel more organic, and like we are at least approaching his settings and events ourselves, his English language debut is hilariously so self aware about how its target audience will disassociate from a character that basically resembles all of us. We’re transfixed by photography and cinema (essentially its own type of photography) and what is captured, but if you place us with the capturer, the feature no longer rings true. Despite all of the strangeness in Blowup, I would argue it is much more real than the majority of motion pictures we consume.

Blowup may be fragmented and not uniform, but it is also a highly stylish affair, as if each part was its own editorial in a fashion magazine (and we have the fantastic framing and focal points to confirm this). What do all of these entries in this living digest say? Are we reading too much into the processing of photographs that may have uncovered a murder? Should we let it just exist? What about the rush of the concert sequence, where guitarist Jeff Beck begins to destroy his own instrument on stage out of frustration? The tennis scrimmage between mimes? I would say that nearly each and every sequence in Blowup is the adjustment of normalcy; the photograph is no longer beautiful because of the corpse that we can no longer look away from; we hear the music fall apart once one of the key elements of the harmonious union tears itself away from the whole; we don’t watch the game but the athletes instead. Again and again, Blowup challenges us to become acquainted with a new normal. It gives its title a number of definitions, including the photographical sense of blowing up a picture to examine it more closely, but I also find the likely unintended definition of the breaking-apart caused by detonation to be equally as fitting. We’re scrutinizing and deconstructing all at the same time.

Blowup is a stylish take on postmodernism that results in an unforgettable experience.

Consider this: one of the greatest films of the 80s — Brian De Palma’s Blow Out — is inspired by only one of the many storylines here, and it also feels like a massively refreshing take on its own genre (the mystery thriller). What does that say about Blowup? It has to be considered one of the most unique films of its time (and quite possibly ever). It feels incredibly at-home with the French New Wave works of the same era, but also like the best approach to what the Brits were trying to achieve with their cinematic bouts of unhinged freedom; considering Michelangelo Antonioni was neither French or British, I would say the student outsmarted most of his teachers here. Blowup feels singular even within Antonioni’s filmography, like this was as out-there as he was willing to go. The film invites you into a series of exclusive worlds without allowing you to truly get a taste of any of them; instead, you get walloped with the kind of self-dreading alienation that you would likely succumb to in such scenarios. We begin to wonder what pop culture truly is and why we allow it to guide us. It was the only flirtation with the mainstream that Antonioni ever got, and it is so typical of the auteur when you really look at it. Then again, I’m highly grateful for Antonioni’s peculiar take on popular “art”, because it’s the closest it ever got to being truly artistic in the classical sense.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.