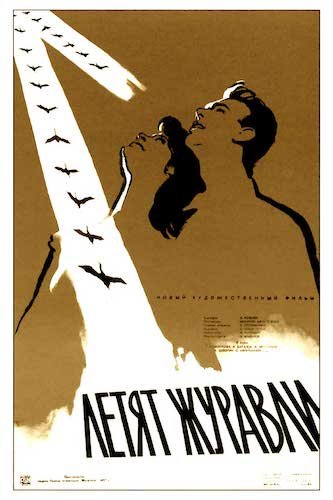

The Cranes Are Flying

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. The Cranes are Flying won the fourth Palme d’Or at the 1958 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Marcel Achard.

Jury: Tomiko Asabuki, Bernard Buffet, Jean De Barnocelli, Helmut Käutner, Dudley Leslie, Madeleine Robinson, Ladislao Vajda, Charles Vidor, Sergei Yutkevich, Cesare Zavattini.

When I started the Palme d’Or project (the reviewing of every winner from when the award was first given in 1955 until the present), I had a few motion pictures in mind that had me itching to complete my ongoing dream of watching these winners. One major film that had me feeling this way is The Cranes Are Flying by Mikhail Kalatozov; one of the greatest films I’ve ever seen, and most certainly a highlight of the 1950s. This feels like the quintessential Palme d’Or winner: a film that feels like it was made thirty years after it actually was, with the artistry of the wisest auteurs of yesteryear and the imagination that feels like the film was made with both the head and the heart. I dare anyone to watch The Cranes Are Flying and honestly tell me that this feels like this film was released in 1957. You’d be lying if you said it does. Just face the facts that this film was eons ahead of its time, because it deserves that recognition.

Kalatozov has a strong team behind him, particularly Sergey Urusevsky (who is unquestionably one of the greatest cinematographers of all time) who is exemplary with his wide shots and even better with his extreme close ups. There are camera tricks and ideas here that just puzzle me, not just because I cannot fathom how they were pulled off sixty five years ago but also because I don’t get how there weren’t numerous filmmakers trying to bite this film’s style. Maybe its gradual releases made it under seen (it was only shown at Cannes a year after it was made and then released on a wide level in 1960), or there’s the fact that maybe the finest cinematographers of the time also couldn’t figure out what Urusevsky was doing (please see I Am Cuba for even stronger filmic mastery). These images are perfect for displaying war-torn Moscow (this is a World War II picture) and the broken souls that have faced the worst of humanity.

The Cranes Are Flying is one of the best shot films of all time.

The story is quite simple and it involves young, fleeting love (Boris and Veronika). Veronika is played by the underrated Tatiana Samoilova, who carries this picture upon her shoulders and treks into some of the difficult subject matters with complete confidence. The actor of Boris, Aleksey Batalov, is also quite good at representing a familiar face that is due to be sent to war (after he volunteers); he sticks out particularly well in your mind when he is absent. These salad days are about to be destroyed once Germany fulfils Operation Barbarossa and infiltrates the Soviet Union, but The Cranes Are Flying keeps us in the loop of Veronika and Boris’ happy times together. These are brief moments, but they are enough to keep us trekking through the harrowing monstrosities of war. Everything that comes afterwards is uncomfortable, despite being framed so nicely.

The Cranes Are Flying is prepared to place us in unfortunate predicaments not just on the battlefield, but at home (and even more so at home, quite frankly). What does someone do if their loved one is away in combat? Do you move on? Wait? I think we all have our own answers, and most of us would pick “wait”, but The Cranes Are Flying really tests us with this choice by making its protagonist have to face such a predicament head-on, particularly within the entanglement of depression and the pits of despair. There is virtually no love in one’s homeland when it is being ripped apart, and there can be a yearning to feel warmth again. It’s not preferable, and The Cranes Are Flying knows this. During a time where films picked sides during the war or focused solely on the battlefield or aftermaths of war, The Cranes Are Flying provides a different angle with as much sympathy as it can muster.

The Cranes Are Flying provides so many angles of what happens during wartime.

I won’t spoil the breathtaking finale, but The Cranes Are Flying brings tears to my eyes every time it resolves. It sticks its landing, knowing that the previous hour and a half of social realism whilst memories were still fresh will resonate with anyone that abhors what wars do to families, lovers, friends, or pretty much anyone; you can be shredded as individuals and not just stripped away from others. Kalatozov supplies this difficult film with loads of tenderness, as if it is telling us these hardships whilst consoling us. For a war film, The Cranes Are Flying is unspeakably stunning, and it is guaranteed to drill its way into your very soul. It is artistically brilliant, poetically resonant, and narratively bold. It’s the kind of motion picture that revitalizes the sensation that films can feel magical (even at their darkest), and I feel that spell reborn every time I revisit The Cranes Are Flying. It is a tense watch as a member of humanity (particularly watching how awful we can be), but I can’t help but feel rejuvenated as a cinephile.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.