Kagemusha

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Kagemusha won the twenty fifth Palme d’Or at the 1980 festival, which it shared with All That Jazz.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Kirk Douglas.

Jury: Ken Adam, Robert Benayoun, Veljko Bulajić, Leslie Caron, Charles Champlin, André Delvaux, Gian Luigi Rondi, Michael Spencer, Albina du Boisrouvray.

The film industry can be a fickle one. By the 80s, Akira Kurosawa was beyond recognized as a vital storyteller. Rashomon won him the Golden Lion from Venice early in his career (and fragmented storylines would forever be inspired by him). Seven Samurai revolutionized how action and combat was shown on screen. Yojimbo was his answer to the great classic western, and the genre would respond back (A Fistful of Dollars for this film, and The Magnificent Seven would stem from Seven Samurai). Hell, The Hidden Fortress is the entire blueprint for Star Wars, and it is as clear as day in hindsight. Most of the biggest filmmakers had Kurosawa to thank for their visions even during his life.

This is why it is still shocking to me that the industry was so willing to just let him struggle during his career low-point: many backs were turned on him, as if he didn’t matter. After his first significant bust (Dodes'ka-den), he only made one other film in the 70s (the Soviet feature Dersu Uzala). The former has been reexamined in hindsight and the latter was beloved upon release, but Kurosawa was still left in the dust as an artist. The two faced mentality of the film industry was real. He was working on getting back on his feet with Kagemusha: a narrative return to form, considering the theme of Samurais. Toho ran out of the money necessary to complete his film. George Lucas and Steven Spielberg never forgot his contributions to film, and helped him finish Kagemusha through 20th Century Fox. What a lovely anecdote: there couldn’t be a bigger thanks to the visionaries of yesteryear than this.

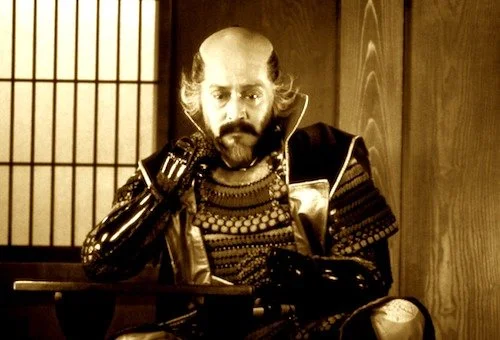

What we ended up getting was a huge aesthetic departure for Kurosawa. The director is usually synonymous with his perfection of greyscale photography. Now, we have one of the most vibrantly coloured films of its time. This was highly unusual for Kurosawa who would experiment with colour quite a lot during his latter years (starting with Dodes'ka-den), and it’s great to see how he would approach the visual style. We get our answer: with extreme vibrancy. As said before, the story is the kind you could expect from Kurosawa by now. A rescued criminal is granted the ability to live again because he is a dead ringer for magnate Takeda Shingen and can be his double (as to protect the political figure from any harm). He has to live this new trajectory, because he won’t live otherwise (he was facing execution before being saved for this mission). This proves to be even more challenging when the actual warlord dies, and this double has to replace him secretly for good. This seems like the kind of yarn that only Kurosawa could spin.

Kagemusha was a very welcome return for Akira Kurosawa: one of film’s greatest masterminds.

Again, the visual palette for Kagemusha is borderline neon at times, which is incredible for a film literally titled after the concept of shadowy doubles (the title translates to “Shadow Warrior”). Perhaps Kurosawa’s influence was that of the old operas whose stories he would draw inspiration from. His black and white films would pop, yes, but they felt more uniform. Kagemusha is all noticeable and you don’t really see films like this anymore. All the whole you are seeing a tale of dichotomies, deception, and falls from grace. The entire film feels like a daydream: a grand story that you conjured up as an escape from what is going on around you. And yet it doesn’t seem to be explicitly surreal, even when it fully seems like Kagemusha intends to be so. We are still deeply rooted within corrupted regimes and misguided power struggles enough that we can see many similarities within our own contemporary wars and calls for revolution here.

Kagemusha is a late career statement from a filmmaker that should have never been forgotten. It took some support from friends in high places to get Kurosawa where he and his film needed to go, but it was worthwhile. It would win the Palme d’Or: tied with All That Jazz. It was Kurosawa’s only win of this particular award, but it meant something. His style seemed different (for those that lost interest the previous decade), but his bare bones signature style of narrative complexity was there. No one could command the screen like Kurosawa. It seemed effortless for him. He knew how to reach all corners spatially, and how to connect to audiences of all walks off life: the screen was his to own in any capacity.

Kagemusha is a visual feast that is a borderline psychedelic experience at times.

What would come after Kagemusha is Ran: one of the greatest epics of all time. It was similarly colourful but even more daring, and it is arguably Kurosawa’s masterpiece. I feel like Kagemusha walked so Ran could run (I swear no pun is intended here). The former feels as though Kurosawa was testing the waters after a decade of neglect: to see if he still had it when it came to Samurai films. He sure did. Now, it was his chance to go even further. Sadly Ran would not win the same top prize at Cannes, but at least its previous film was noticed. Maybe this successful festival run is what Kurosawa needed to kick start the final era of his career, as he would keep going even after Ran. Where does Kagemusha fall in his filmography? He’s made so many perfect films that it is tough to compare, but Kagemusha is still a great watch. I will say that Kagemusha was one of his most important films. It placed life back into his art, and we are all very grateful for this second wind. It allowed a cinematic giant to bow out on his own terms: an opportunity he should have been granted automatically. It proved that the best directors will always have something to say. Kagemusha may not be Ikiru, High and Low, or any of the other classics I’ve brought up already, but it stands on his own as an awaited return, a more-than-solid release by a master, and a foray into Kurosawa’s untapped remaining excellence.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.