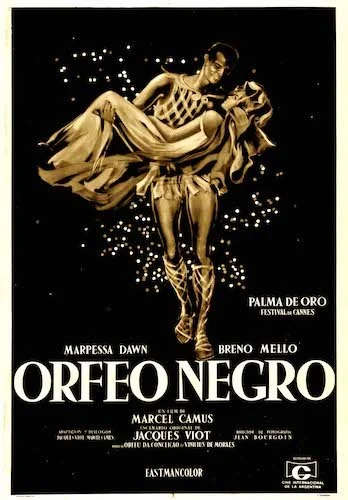

Black Orpheus

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Black Orpheus won the fifth Palme d’Or at the 1959 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Marcel Achard.

Jury: Antoni Bohdziewicz, Michael Cacoyannis, Carlos Cuenca, Pierre Daninos, Julien Duvivier, Max Favalelli, Gene Kelly, Carlo Ponti, Micheline Presle, Sergei Vasilyev.

We’re used to the zillion adaptations of William Shakespeare’s writings, but occasionally we get a similar treatment (where creative liberties take a hold of orthodoxy) of other large tales. Marcel Camus’ Black Orpheus is such a case, and it is a musical, colourful spectacle for such a tragic tale. This is a pure celebration of a motion picture, and its infectious energy is impossible to shake off. Instead of ancient Greece (as per the mythology of Orpheus and Eurydice), we head to Rio de Janeiro during the Carnival of Brazil. If you’re familiar with the original mythology, you’ll be expecting a heartbreaking tale of sacrifice in the name of love. If not, it may be wise to know the spiel before we carry on. Musician Orpheus — son of Apollo — fell in love with the beautiful Eurydice, who died via snakebite and had her soul sent to Hades. Orpheus uses his music to attract Hades, and his plan works; Hades promises that Eurydice can be brought back to the living world. However, there is one condition: Orpheus cannot look back at Eurydice until they both make it back to the world. At any point during this climb back to reality should Orpheus look back, she remains dead forever. He couldn’t hear her and began to doubt this deal, and right at the lip of the path out of the underworld, Orpheus turns around to see if Eurydice is okay or even there; his insecurity damned her forever, and she was pulled back when she was mere moments away from life again.

So, how does this translate to a celebration in Brazil? Camus went off of Orfeu da Conceição (a play by Vinicius de Moraes) as his major source, and he turns this entire picture musical (rather than having just a central character be a musician). Orpheus is now Orfeu, who is engaged to Mira; the myth that the film is based on exists in this reality, as Mira is actually asked if she is Orfeu’s “Eurydice” early on. I brought up the works of Shakespeare as a comparison earlier, and Black Orpheus reminds me a lot of West Side Story, particularly the modernization of particular elements in ways that feel applicable in our own societies. The handling of the whole Hades/underworld is quite interesting, but I won’t spoil how Camus adapted this particular portion of the legend. It’s worth seeing the rewriting come to fruition. Part of Black Orpheus’ attraction is how imaginative this version is, especially surrounding such a beloved and idiosyncratic tale.

The rewriting of an old legend makes Black Orpheus an immediate draw.

The other major reason to watch Black Orpheus, and perhaps why it won the Palme d’Or, is its artistic mastery. It’s the kind of film that revitalizes the sense of magic and spirit back into your soul, and it feels impossible to not ingest this film on a cosmic level. The bossa nova soundtrack ties the entire film together, but it is also impossible to deny the richness of the photography, the gorgeous costumes, and the elaborate sets that transport us to a new world, even though this version of the story is based on real celebrations. The mythological component is still alive, even in this different rendition. Not many films feel quite as alive and vibrant as Black Orpheus, and it’s easy to see why it would win over many people. Hell, it won me over and has stuck with me for many years, even though I’ve only ever seen it once. The film still resonates in my head in a bit of a faded way, but its aura remains in my core.

What didn’t age as well, however, is the heavy European gaze on Black culture and people, and it’s something that even President Barack Obama has commented on when reflecting on his mother’s favourite film. He equated the characters as “childlike” and the fantasies of white viewers of the '50s that were detached from these kinds of celebrations; this could be their foray into another world, but it is a very one-sided depiction. While I don’t agree with Obama entirely, I do see where he is coming from, and there is still a datedness with how race is treated in Black Orpheus (I mean, the title alone is a bit of an indicator), but I don’t think there was any disrespect intended. There’s most definitely a misguidedness in ways, but I feel like the lack of malice is what helps Black Orpheus remain a celebratory film and not a sour depiction.

Black Orpheus is a massive celebration of a film.

That’s the one issue that the film has; otherwise, Black Orpheus is an absolute, filmic treat. It begins with an image of marble relief of Orpheus and Eurydice, signifying what was told once before. Upon release, Black Orpheus vowed to go the distance with this tale of loss and regret amidst a dynamic and lively backdrop. It’s a film that has its fans nowadays, but I find it is more discussed within the context of the Palme d’Or itself (the film went on to beat The 400 Blows and Hiroshima Mon Amour, which is kind of mind boggling; I love Black Orpheus, but damn). It’s the kind of picture that embodies the adoration of creativity, technical prowess, and spirit that Cannes seeks time and time again. It just feels like a quintessential Palme d’Or winner, and so that is how it will most likely be remembered by many.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.