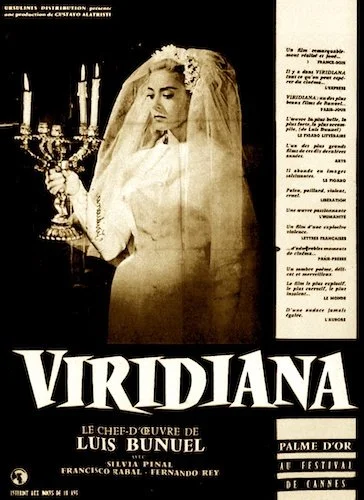

Viridiana

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Viridiana won the seventh Palme d’Or at the 1961 festival, which it shared with The Long Absence.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Jean Giono.

Vice President: Sergei Yutkevich.

Jury: Pedro Armendáriz, Luigi Chiarini, Tonino Delli Colli, Claude Mauriac, Edouard Molinaro, Jean Paulhan, Raoul Ploquin, Liselotte Pulver, Fred Zinnemann.

What would the Palme d’Or be without the inclusion of polarizing pictures? Imagine this: a film that is acclaimed as one of the finest motion pictures in the history of Spanish cinema whilst having been banned from the very country it was made in (additionally, the Vatican — which has exhibited some strong tastes in film — has dismissed that it even exists). This feature is Viridiana, one of Luis Buñuel’s finest works (if not his magnum opus, but that is very difficult to decide upon unless someone had a gun to my head). The visceral responses that Viridiana illicit (both of astonishment and of repulsion) come from the fact that the film is the perfect bridge between middle-era and late-era Buñuel. His earliest works indulged in surreal and avant-garde sensibilities, but he opted for some more direct cinema in the 40s and 50s, particularly because he had many satirical and/or neorealist comments to make (he never fully abandoned surrealism, mind you). If you think of the last few films Buñuel would make, he fully stopped caring about how his works may be perceived as he embraced postmodernism and his most scathing declarations, but I feel like this descent towards his most vicious films starts here.

So, why does this deserve a divided response? Viridiana is as literal as it is symbolic, and all of its parts point towards Buñuel’s disdain for organized religion (or religion in general); it is ironic that the Vatican that would disregard Viridiana would also commend his film Nazarin, whose tongue-in-cheek nature that actually points fingers at the church may have been missed when it was selected as one of the finest films that exemplify religion. Something like Viridiana doesn’t care if you are in the line of fire of what Buñuel wants to say about Christianity, so I do warn my religious readers should you be interested in watching the film. Having said that, stifling one’s self is not the way to exhibit the purest of artistic intentions, and sometimes viewpoints that aren’t agreed upon are the end result. I believe Buñuel understood this, and likely felt like those that are wanting to watch his films for artistic or communicative purposes would have the same notion, and those that are willing to get upset will just fold. Again, Buñuel is as relentless as ever in Viridiana, but his dream-like obsessions translate these scorns into haunting images that are nearly ghost-like.

The freeze-frame replication of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper is a stand-out moment of Viridiana, particularly when the film is at its most unhinged.

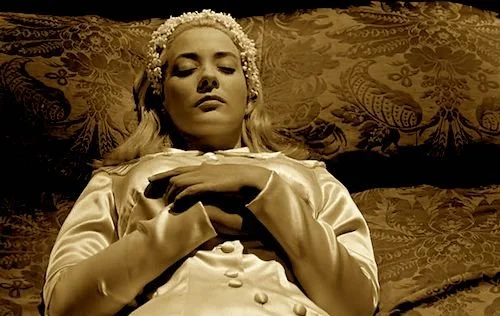

Buñuel presents the setting of a farm as some sort of a demented diorama for the titular character — a novice that is wanting to ascend towards purity — to be placed in (like the beach in Persona or the mansion in Parasite). This farm is her uncle Don Jaime’s: a widower who has slowly gone insane due to his loneliness and the mundanity of life. The film begins with some signature church music (Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus”), but don’t be fooled by this bait-and-switch. Viridiana will remove all of your senses of comfort rather quickly. The film feels like a practice of minimalism for a little bit until Buñuel starts to showcase his true colours, and Viridiana feels like such a glacial crawl towards madness that you yourself may start to question what you are even seeing. The farm no longer plays like a destination but a limbo instead, as the apparitions of conflicting viewpoints and values collide into chilling imagery. This is only the second act: the third goes full-on anarchistic in ways. It’s as if Buñuel discards the rulebook at a certain point and does whatever the hell he feels like, and there’s something beautiful there: if he is using an entire feature film to chastise the sterile censoring and hypocrisies of the Bible (in his opinion), he shouldn’t be playing by any other book either.

In fact, he full-on winks at the audience during the final act with a freeze frame that resembles Leonardo Da Vinci’s Last Supper (albeit made up of rowdy beggars): it’s the kind of forwardness that makes you feel like you’re in the hands of a director with complete control and zero bother. Of course, this shot comes well after the many desecrations that take place within the farm, which is essentially treated like the house of God (think of it as Mary and Joseph’s resting at the manger for Jesus Christ to be born). Once Viridiana abandons coherent semblances, you basically zip through his own version of Biblical allegories, ranging from the many sins found within the hearts of those that reportedly practice righteousness, the destruction of faith, and the realizations that values won’t protect you from outside harm. Viridiana holds zero punches, and it’s the kind of slaughtering that is destined to upset many viewers, but this all comes from an artist that feels like he is livid with the excuses that people allow in the name of keeping appearances.

Once Viridiana truly gets going, it possesses some haunting visions.

So, yeah. I can naturally see why this film would bother many, but I also find Viridiana to be one of the most uncompromising films of the 60s. As cinematic art, this is an eminent experience. The trajectory from uncomfortable reality towards a complete collapse of tone and structure (with some absolutely shocking moments tossed in every so often) is a guaranteed unpredictable experience whose metaphors will sting more than its surprises. it feels strange to even place Viridiana inside of a labeled box. It’s a full blown satire, but far from an entertaining observation. It is a compelling drama, but it also doesn’t succumb to traditions and expectations. It is as straight forward as it is chaotic. If Buñuel wasn’t so adimant on his stances against Catholicism, I’d swear this was a transcendental (in a cursed way, mind you) experience that places you and all of its characters out of their own bodies to stare at their mannequin-like corpses as they try to continue on in a lifeless void of existence. You’re guaranteed to sit in your seat speechless, either with pure rage or incredulity. Sometimes, this kind of challenge is what it takes to win a Palme d’Or because you know a film like Viridiana worked on you either way. Whether you despise it or adore it is entirely up to you. I think it’s impossible to ignore.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.