The Umbrellas of Cherbourg

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

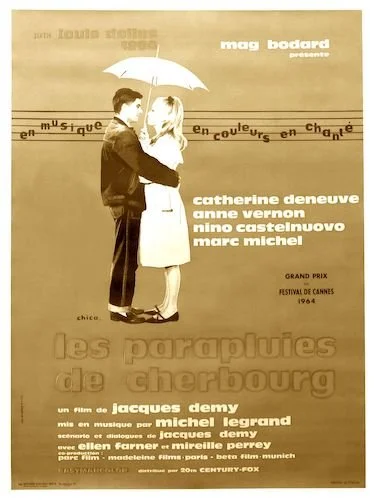

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg won the tenth Palme d’Or — temporarily reverted back to the Grand Prix — at the 1964 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Fritz Lang.

Vice President: Charles Boyer.

Jury: Joaquín Calvo-Sotelo, René Clément, Jean-Jacques Gautier, Alexandre Karaganov, Lorens Marmstedt, Geneviève Page, Raoul Ploquin, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., Véra Volmane.

When Damien Chazelle’s La La Land took 2016 by storm (this was before the world wanted to start over hating it), another filmmaker’s name was starting to make its rounds for a new generation: Jacques Demy. His musicals — particularly The Young Girls of Rochefort (which was a major influence on Chazelle’s film, alongside the film that’s the subject of this review) — were being talked about en masse for the first time in an eternity, and it is with this lens that we could spot that a number of his works haven’t aged a bit. Case in point, here’s The Umbrellas of Cherbourg: a pitch-perfect then-contemporary opera that has risen in the ranks of the greatest musicals, and whose very essence alone makes it an automatic consideration as the greatest musical for some. For me, this is ultimately a top ten musical, if not a top five. It is stunning in every sense of the word.

Demy felt indebted to the Hollywood musicals of someone like Stanley Donen, but he also wanted to rely less on the songs and styles of others and more on the creations he could muster himself (alongside the legendary Michel Legrand, who composed the music for the film). The entire picture has a score throughout, with nearly every line sung (the majority of the performers had their lines dubbed by professional singers), and this turned the everyday habitual slog into an exquisite suite of beauty; it feels like the quest Brian Wilson was on when he was making Smile. It feels wrong to call the story within The Umbrellas of Cherbourg basic because of how much radiates off of the screen even amidst this narrative simplicity. The picture is driven entirely by its heart, and it shows. Why bother over-calculating and dulling the high that the film gives you?

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is an infectiously fanciful musical.

If anything, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg feels like a daydream where life is passing you by and your desires for something less dull have painted the world around you. Suddenly, even the bland seems inspirational. We learn about young Geneviève, who runs an umbrella shop with her mother and is struggling to make ends meet (despite the call for umbrellas to protect people from the rain, this just isn’t enough). Geneviève falls in love with Guy, who is drafted to fight in the Algerian War. You don’t need to know any more than that. Let life unravel. In the same way that life can happen right in front of your eyes, it can also just zip by, and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg also details this sensation. Where did all of the years go? How did we get here? Because of the continuous musical cues, the film doesn’t feel like it is missing anything. We just feel like life is exceptionally short, and it can end as soon as you blink. It’s this idea that Chazelle was pining for when making La La Land: existing is a miraculous occasion, but it is also a fickle test that challenges what we appreciate and how.

If Chazelle is inspired by Demy, then Demy — again — is inspired by Donen, and I can’t help but think that The Umbrellas of Cherbourg was marginally indebted to Singin’ in the Rain, with the obvious metaphors anyway. If Donen (and Gene Kelly) made their opus with the idea that one can smile in the face of adversity (in their case, it was about performers transitioning from the silent era to the dawn of talkies), then Demy was associating the metaphor of rain as the constant tribulations of life, and how you can weather them with the help of a plus one (say, an umbrella, or a loved one). You can also face the rain alone, but you feel more secure when you’re protected. The speed of life also feels equal to that of a rainstorm, either by the pitter-patter of the droplets and their frequency, or by the clearing of the storm itself (and our response that it didn’t last long). The Umbrellas of Cherbourg also feels seasonal in other ways, particularly its use of snow in its bittersweet climax (perhaps a sign of acceptance for life’s constant problems, and the embracing of these issues head-on with a smile and a full heart).

Weather is utilized brilliantly in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.

Whether you leave The Umbrellas of Cherbourg with a smile on your face or a tear rolling down your cheek, you will be touched by Jacques Demy’s masterpiece. Not just any musical would win the Palme d’Or (or, excuse me, the Grand Prix, as it was temporarily known as), as is evident with other winners All That Jazz and Dancer in the Dark. The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is much more optimistic than those other two works, but even then it had to be special for Cannes to find it sensible to rate it higher than any other film of 1964. Many musicals seek the fantastical escapism that this film pulls off effortlessly, but The Umbrellas of Cherbourg also stares in the face of reality quite seriously. It acknowledges that its feel-good tone is temporal, and we will return to our awful lives quite shortly; at least now we will have a tune and some warmth in our heart as we embrace the precipitation ahead.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.