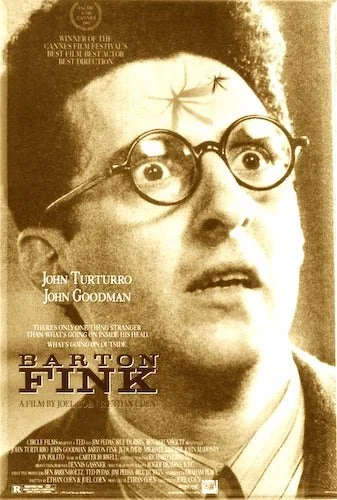

Barton Fink

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Barton Fink won the thirty sixth Palme d’Or at the 1991 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Roman Polanski.

Jury: Férid Boughdir, Whoopi Goldberg, Margaret Menegoz, Natalya Negoda, Alan Parker, Jean-Paul Rappeneau, Hans Dieter Seidel, Vittorio Storaro, Vangelis.

Have you ever had writer’s block? So have many of the greats. Federico Fellini’s 8 1/2 set a precedent for what a filmmaker’s struggles with creativity can look like, and many directors have responded. It was really early when Joel and Ethan Coen threw their arms up in the air and admitted imaginative defeat with only their fourth feature film (other directors lasted longer), Barton Fink. Then again, were the Coens actually strapped for ideas, or were they just wanting to be a part of this exclusive club for auteurs bereft of inspiration? I’d argue the latter, because Barton Fink is actually a highly artistic dark comedy: not due to the drying of the cranial well, but the exploration of what lay ahead for the sibling auteurs. They wanted to try anything and everything, and didn’t want to wait to need to make their 8 1/2. That was high up on their to-do list. Barton Fink actually came about during the production of Miller’s Crossing, and it was an excursion away from the writing process of the latter, so technically there was some writer’s block at play here, but I think this being a writing exercise to help the Coens get back on track (instead of them being completely strapped of thought) helps my earlier claims stay at least partially true.

The Coens have always been interested in going where other American filmmakers haven’t gone before, and enough of Barton Fink feels like their own story and Fellini’s surrealist ideas combined. Not to get too juvenile, but I have to bring up this comparison. Remember the Spongebob Squarepants episode (“Procrastination”) where the titular cleaning device has to write an essay on what not to do at a stoplight, where his stalling results in nightmarish scenarios that are extremely hyperbolic? That’s Barton Fink, down to a literal fire that smokes us out (I can almost hear a ghostly voice asking Fink why he didn’t just finish his script). However, Barton Fink is more than just a film where a playwright cannot get his act together. He procrastinates not out of strain but out of distraction: particularly the discoveries of the “real” side of Hollywood and the American underground altogether (as if he were a Cold War agent trying to dig up dirt). The Coens are after something else here and not just a postmodern story: secret societies and the deception of the American Dream.

As literal as Barton Fink feels at times, it is also quite astonishing in a dreamlike sense.

So the eponymous character is a playwright that has secured a new deal with Capitol Pictures to start doing scripts on a weekly basis, and so he assumes a temporary stay in a run down hotel in Hollywood (he’s in the city of stars and bright lights, but he’s not there there). He begins working on his first such project, but he’s already focusing on his new surroundings rather than honing in on his story. He becomes acquainted with who is next door in the hotel (particularly Charlie Meadows: an overly social guy that cannot keep to himself). He tries to find inspiration in his new space, but instead he finds excuses. The quest to get something done isn’t even to prove something artistically, but because Fink is now on the clock: he has to answer to powers that are greater than him. He went from meaning nothing to meaning too much (we have all certainly been there).

Seeing how ridiculous Fink’s predicaments get feels almost rewarding for us viewers, because we have had to face the utmost of distractions before (okay, they may not get Barton Fink bad, but they feel like they do in our own heads). One element I love is that the film does progress beyond its premise of Fink’s creative struggles. If anything, we see at least a little bit of progress in ways, but it’s around the time that the film goes beyond this gimmick anyway. Fink is just a storyteller, but it’s as if he’s a sleeper agent placed amidst his enemies, in an unknown place. His frustrations turn into paranoia: why even bother worrying about a stupid screenplay when there are bigger problems at hand? The ways that he listens to interferences so attentively are exactly the ways that he himself may be spied on. All he wanted was to make a name for himself. He’s going to be known for far too many reasons now; as a Hollywood degenerate; as an accomplice; as a nobody (contradictory, I know, but it makes sense if you think about it).

Barton Fink uses diversions so expertly to get us invested in a story about being caught up in it all.

Barton Fink saves its best cards for last, as it allows the Coens to fully pull the rug from underneath us. It’s almost like an antithesis next to a film like Adaptation., where the surrender to conventionality is the only way out of the entrapment of exhausted creativity. Here, the Coens actually stray as far away from expectation as possible. It actually gets borderline anarchistic, and I think that’s the only sensible way Barton Fink could have wrapped up. Even when the film seems in control of itself, it actually isn’t. That’s not out of surrender, but rather the result of the Coens being so masterful at filmmaking that they can feign obliviousness. Really, this open-ended conclusion is precisely calculated, as can be seen from earlier hints (particularly the photograph that Fink keeps gazing upon): the writer’s disturbances become his desires. We would only get more familiar with the interesting minds of the Coen brothers as their filmography kept going (rarely did they have a hiccup), but Barton Fink was the first sign that these weren’t just sibling storytellers of the American experience: they were directors that were here to finesse the medium they loved so dearly. They have been great since their blistering debut Blood Simple, but Barton Fink was the turning point where they went from new directors to watch to being some of the directors of their generation: completely unfazed by challenges, and capable of going where we would never expect.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.