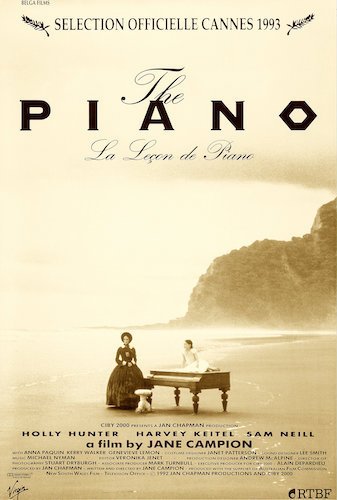

The Piano

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. The Piano won the thirty eighth Palme d’Or at the 1993 festival, which it shared with Farewell My Concubine.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Louis Malle.

Jury: Claudia Cardinale, Inna Churikova, Judy Davis, Abbas Kiarostami, Emir Kusturica, William Lubtchansky, Tom Luddy, Gary Oldman, Augusto M. Seabra.

Oh, how I adore The Piano. One of the greatest period pieces of all time, Jane Campion’s mesmerizing feminist drama has been a must-see film since it was first released; had it not been the same year as Schindler’s List, it would have been the first female-directed film to win Best Picture at the Academy Awards (and Campion’s Best Director win would have come decades sooner). No matter, because The Piano was built to withstand the test of time: not to only win awards. My curiosity connected to the film has existed since I was a teenager back in the mid 2000’s: discovering this mysterious film where a mute mother is arranged to marry a stranger she doesn’t know seemed interesting. Learning that Holly Hunter won Best Actress without uttering a single word (sort of), and that Anna Paquin also won an Oscar (Best Supporting Actress) at the second youngest age ever (eleven; next to Tatun O’Neal’s win for Paper Moon at the age of ten) was all I needed to get started. I wasn’t expecting much outside of some great acting. I was also a stupid teenager. Well, I couldn’t have been that stupid: I discovered one of the greatest films of the 1990s out of some sort of fascination (and it was so much more than I had bargained for).

Before I can even continue with the story (a punishing love triangle that’s more of a feminist statement than a set of romantic trysts), I must get into how Campion is one of the finest directors to ever make period piece features. I won’t lie: I oftentimes watch period piece films and am painfully aware that I’m watching performers in fancy costumes and on elaborate sets. Some directors can place me under a spell and have me at least partially forget that I’m watching contemporary people reenact the past, and one of them is Campion. Not only do I feel like I am actually transported back in time and to a distant country (in this instance, we’re placed in nineteenth century New Zealand), but I am also introduced to so many smaller details that most other directors would completely ignore (even something as private as going to the bathroom is detailed here for educational, transformative purposes). Campion doesn’t just admire the highlights of the eras she captures: she also focuses on the ugliest parts. She humanizes these films. The illusion is as strong as it can get with Campion, and that alone makes The Piano an effortless watch: its extreme believability.

Jane Campion is one of the strongest period piece directors of all time, and The Piano is her primary example as to how.

The world we are introduced to is that of Ada McGrath: a mother who has become mute later on in her life. He lives with her young daughter and interpreter Flora, and the two of them are shipped off to New Zealand so Ada can marry settler Alisdair Stewart. Ada and Alisdair do not get along from the first second they meet, especially when he neglects her prized possession: the eponymous piano. It’s her way of communicating with the world and channeling how she feels, and she is a brilliant pianist at that. The piano has narrowly survived a long trek across the Pacific Ocean and numerous seas (Ada and Flora are from Scotland), and now it is abandoned at the cusp of the shoreline, as Alisdair and his Māori workers have deemed it too difficult to bring the instrument up to the house (it is a challenging uphill trek through forests, to be fair). We quickly are introduced to a fellow frontiersman named George Baines who has actually assimilated within the Māori community enough to identify himself as a fellow member. He takes a liking to Ada and offers for the piano to stay at his place on the condition that she teaches him how to play. This is a ploy as George just wants to come onto Ada, and he is persistent and heavy handed with his sexual advances.

This is a masterful allegory of the female experience from a feminist lens. The piano and Ada’s muteness are representations of the silencing of female voices in patriarchal societies (and this is especially true considering how Ada can’t choose who she ends up with: the business agreement resulting in an arranged marriage to a complete stranger, or a man that forces himself onto her just so she can have a voice again). Ada is caught in a love triangle, but not in the typical way: she loses either way. As she develops love for George over time, we the audience see something a little less black-and-white here: a woman who doesn’t have as much free rein as she may believe. She acknowledges this finally in the film’s gut-wrenching finale: a devastating move indicating someone pushed beyond comprehension. There’s also the frightening climax that carries its own metaphor that I won’t spoil, but if you have seen The Piano, I will detail it as yet another form of oppression, and I’m sure you will know what I mean. What Campion has written here is magnificent, exquisite storytelling with some well-detailed symbols used to embody the female experience of the nineteenth century and the nineties alike.

Holly Hunter delivers one of the finest performances of all time as Ada McGrath in The Piano.

While I can spotlight every performance (Paquin’s natural Flora, Sam Neill’s unforgiving Alisdair, and Harvey Keitel’s cryptic George), I must focus specifically on Holly Hunter’s Ada McGrath, which I will gladly go on record and state is one of the greatest performances of all time. You can read each and every expression on her face, and she can emote more with her reactions than most performers do with all of their capabilities. You get some voice over narration from Ada at the start of the film and right at the end, but you never hear from her again. Everything else is channeled through every move, glance, and breath of Hunter’s, and I cannot emphasize enough how perfect this performance is. Even though she pairs up greatly with each of her peers, I will say that her greatest partner in The Piano is the score by Michael Nyman: a classic in all of film. His music not only illuminates the New Zealand setting around Ada and Flora, but it acts as her thoughts of clarity and/or frustration time and time again. I knew I was in the middle of something magical during the beach sequence, when Ada — playing the piano — spots her daughter Flora doing cartwheels, and Nyman’s score is there alongside Ada’s widening smile and the sparkles in her eyes. It is a rare moment where Ada is genuinely happy, and it punctures my heart just thinking about it.

So many period piece films are made to win awards or to cater to a specific audience. I will die on the hill that The Piano will only continue to get better as time goes on. When I first learned about it in my salad days, I couldn’t find you someone else my age that was even aware of this film; it certainly wasn’t being talked about. Its stature will grow and grow, and that’s evident. Seeing it be released via the Criterion Collection was the final affirmation that this is true, especially now that Jane Campion’s back in the consciousness of contemporary cinema. The Piano is one of the most beautiful, saddening, poignant films you may ever see. It is so textured with conflict and uncertainty, and not once do I feel like Campion believes in the fairy tales of Hollywood and its unrealistic depictions of love. Ada McGrath isn’t left off with promise, but rather just a means to keep going, and it’s the kind of bittersweet release that has to be enough for us. That’s how life is. Rarely do things work out perfectly. Through the ugliness of history that most directors avoid, the one-sided approaches to romance via the male gaze, and the difficult dynamics between all of the characters in the film, Campion was telling us that perfection is a myth and shall never be achievable. In doing so, she gave us The Piano: a perfect film.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.