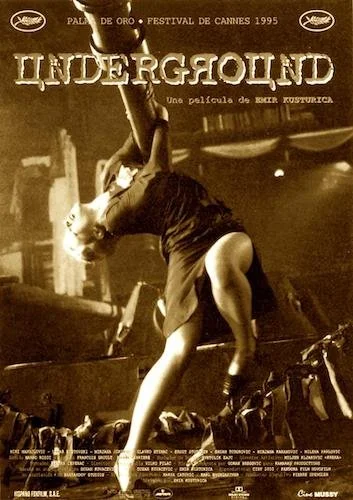

Underground

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Underground won the fortieth Palme d’Or at the 1995 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Jeanne Moreau.

Jury: Gianni Amelio, Jean-Claude Brialy, Nadine Gordimer, Gaston Kabore, Michele Ray-Gavras, Emilio Garcia Riera, Philippe Rousselot, John Waters, Mariya Zvereva.

Of the directors that won the Palme d'Or twice, a few of them felt like they were granted additional crowns as a legacy courtesy of sorts: you're a part of Cannes history already, so you're already in the festival's good books. One of the filmmakers that felt like they deserved this second win, especially because the followup Palme d'Or award was given to a much more worthy film, is Emir Kusturica. His first film, When Father Was Away on Business, was great, but he would definitely go on to do better things. One of those is the indescribable Underground: a hysterical epic that really does exist in its own world. There was no pat on the back here: this is easily a deserving winner and arguably the strongest film Kusturica ever made (if I have to pick between this and The Time of the Gypsies, I may burst a blood vessel).

By now, Kusturica was quite comfortable with his condensing of details into each and every frame (even if the shots glide on a track, there is something new to see at any given second). He was prepared to get as vicious as he wanted to with his political commentary, and there's no where else to go once you've depicted civilization within a bunker left to fester and transmogrify. This is a dark comedy (of sorts), so Kusturica disguises his disdain for how little Yugoslavia was helped during war time with some back handed chuckles (Underground may be an entertaining film for many, but it will hit close to home for its intended viewers). During World War II, Belgrade is toppled over by the bombs deployed by German pilots, and it's a call to evacuate; there's a bittersweet metaphor here when the local zoo's walls are also knocked down, and the animals are left to roam free (but not for long for most of them, I'm sure). Even though we inspect the lives of many, the film is hyper focused on two major characters as studies to analyze their developments: friends Marko and Blacky. You will be sucked in to the stories of all in Underground, but it's the rise and eventual falling out between these two people that will hurt you the most.

The extents that Emir Kusturica is willing to go to to make his hidden society in Underground fully realized are quite far.

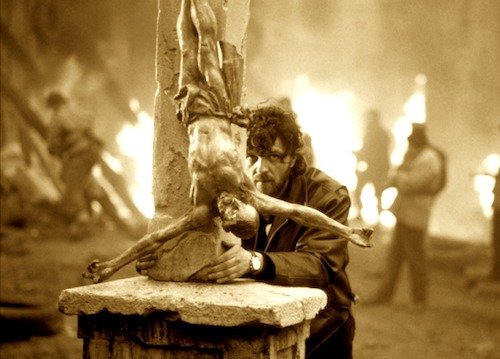

After the bombing, Marko, Blacky, and other civilians retread into an underground cellar, where they wish to hide temporarily. Kusturica isn't this unimaginative to just stop here, and Underground actually keeps these people down there for decades. A hidden society gestates. Laws change. Even a chimpanzee from that destroyed zoo makes its way into this new world and becomes a cherished member. Kusturica is already sour about what war does to society (he has filmed these sentiments before). He wants to test how far a decimated culture can go. In Underground, this society doesn't even know if the second World War is still going on tens of years later, but I suppose that's a safe assumption when there is always war somewhere. In fact, Underground extends to the Yugoslav Wars of the 90s, and that's likely Kusturica's point: when aren't we walking on eggshells because of wartime? Even though we are tucked away from the world, Underground makes sure to leave no combat stone unturned, and you'll feel the breath of other wars happening around their marks during the film; you can definitely sense the weight of the Vietnam War despite the unconfirmed time period in the bunker and the distance away from the battle, for instance. You can even feel this way about the wars that have gone on after Underground. As historically dependent as the film is, it's still applicable to any case.

But what a world Kusturica built here, despite the dark circumstances. I don't know how many filmmakers would put this much care and thought into all of the little things in a possible dystopia, and that sounds silly to say because most filmmakers of this sort go into great lengths to world build. However, you'd need to see Underground to know what I'm talking about. It almost feels like an I Spy book for the jaded soul: there are signs of degradation and the distancing from the rest of the world everywhere here. It's depressing to see what people do in order to survive, but it is fascinating to see how it gets done in this inventive little diorama of the apocalypse. All of the unusual mannerisms and habits of the civilians here amuse me so much. Knowing there are babies here that never saw the light of day, however, does not. At all times during Underground I find myself glued to some elements and then depressed by others. This balance that Kusturica pulls off truly is something. If there ever was a comedy drama epic, this would be it.

No matter how much Underground prepares you, you won’t be ready for its climax.

This all leads to the gargantuan climax, where Kusturica and Underground leave everything out on the screen. I was in love with this film already, but by the gut punching finale, I was completely speechless. If you ever wondered if Kusturica had a sensitive side, this is where you would find it: at the end of horrifying images and complete devastation. This is the finishing touch that leads me to believe that Underground is a stroke of genius. In the way that you would find in Das Boot or Brazil, Underground provides a smidgen of hope before it crushes it in front of you. If you believe you've seen the hardest truths already, you haven't. It's the one moment where Kusturica crosses entirely into the dramatic (nay, tragic) genre in Underground. That is true, unless you consider this conclusion the film's darkest joke: humans won't stop being evil towards one another. They never will. It's wrong to keep lying to ourselves that they well. At least Underground is some three hours where no matter what the odds were, it felt like everything was going to be okay. Now I just need that even longer cut Kusturica has brought up so I can get hooked and emotionally destroyed for even longer.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.