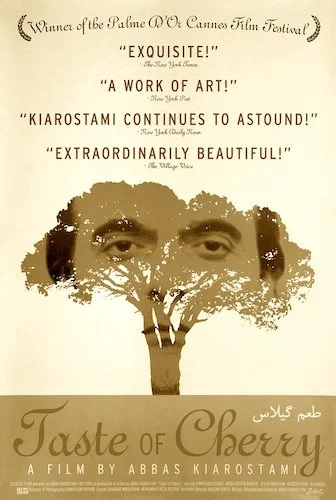

Taste of Cherry

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Taste of Cherry won the forty second Palme d’Or at the 1997 festival, which it shared with The Eel.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Isabelle Adjani.

Jury: Gong Li, Mira Sorvino, Paul Auster, Tim Burton, Luc Bondy, Patrick Dupond, Mike Leigh, Nanni Moretti, Michael Ondaatje.

Warning: this review and the film Taste of Cherry heavily deal with the topic of suicide. Reader discretion is advised.

Abbas Kiarostami was obsessed with blurring the lines between narrative and real life. He experimented time and time again; the reenactment of lies told by the actual people that these events entailed with Close-Up; the boiling down of an entire lifetime into a day with Certified Copy; do I even need to get into the complexities of the Koker trilogy (the examination and reexamination of a story)? Most cinephiles likely know him for Taste of Cherry: what deceptively feels like his most straight forward film until the bitter end. It was polarizing upon release, with some critics raving about this new Iranian classic, and others calling it unfathomable boring. Taste of Cherry is what you make of it, like life itself. You don't enjoy the film. You exist beside it and/or within it. It's to watch the end of a life unravel before your very eyes. There's no entertainment here: only art.

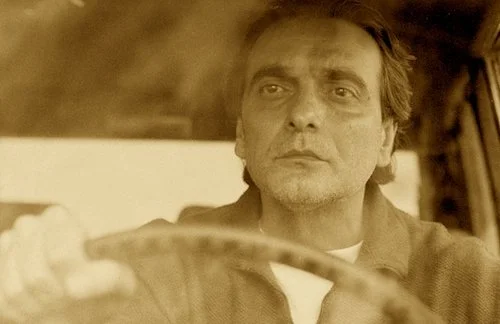

Mr. Badii drives around in search of a willing participant that will fulfill one simple task: to bury his body after he kills himself. His fate is unknown, because he holds some reservations, but he at least wants to try to commit suicide. He is willing to pay a large sum of money to whomever is willing to supervise his potential death, as to ensure he is properly buried afterward. The grave is already dug underneath a cherry tree. All that is left is for Badii to find someone to help him out: if he is going to die, he will do so the right way. Obviously, a number of encounters don't go the way Badii would hope, but who would want to help a stranger end their own life? It's something Badii may have predicted, but you can't help and wonder if these strangers are helping him change how he feels about living. We don't even know that Badii wishes to die right away. We learn this through his candid revelations with the random people he picks up. Otherwise Badii, and the film, tell us nothing. We're shown everything to assess for ourselves.

Abbas Kiarostami slowly reveals the purpose of Taste of Cherry bit by bit, allowing us to take in each and every startling revelation.

As Taste of Cherry progresses and moves into the territory of inevitability, there is no more talking: only action. Even though we've been warned many times by now what Badii wants to do, we still aren't prepared for what is to come. Taste of Cherry certainly doesn't feel like a film in this way: don't narratives have twists, turns, set ups and crescendo? Not this one. This is only a film because it exists within the medium. Otherwise, this is a whole different kind of conversation: a spiritual fusion between the living and that who is soured by life itself. As someone who fights with depression myself, I found myself fighting for Badii to keep going, and thus found light within myself. We can change our decisions, but not a character in a film whose fate has been predetermined by screenplays, photography, and memory of a linear art's tale being burned into our minds.

It is during the final moments that Kiarostami pulls the rug entirely from underneath you, and indulges in his obsession with the shattering of boundaries between narratives and documentaries. It's a bait-and-switch of emotions: depression gets shoved aside by confusion. In this realm, nothing has to end if it can't end, whether it be life or a film. Kiarostami questions what an ending even is with these metaphysical shots that wrap up Taste of Cherry: one of the boldest moves I've ever seen in a film. It's the kind of risk that has actually ruined the experience for some viewers, whilst enhancing and re-contextualizing what it all means for others (like myself). It's not like this is an anecdote or aside. This is as much a part of Taste of Cherry as everything before it. It's Kiarostami's ultimate way of showing how he loves life: behind a camera. I recall only thinking about the ending for days after my first viewing of Taste of Cherry. It's a postmodern easter egg for those of us that are arthouse obsessives: a takeaway that will forever challenge you as a viewer.

The ending of Taste of Cherry (both the narrative’s conclusion and what comes after) are some of the most effective of 90s cinema: both halves are completely unforgettable.

Life means so many things, and Taste of Cherry only scratches the surface. Then again, being buried beneath a cherry tree will only give you a tiny hint of all of the other cherries. If we are each a cherry on the tree, there are so many other cherries, branches, and leaves that we know nothing about. Kiarostami knows this. It has been his life's mission to try and bottle as much about being alive in his films as he could. Despite being enveloped in death, Taste of Cherry is a celebration of being here and present. It's our call to action to find purpose, if we spent the duration of the film trying to justify a stranger's existence. Taste of Cherry is unfiltered, unsweetened, untainted cinema, as was usually the case with Abbas Kiarostami. It could very well have been the closest to the truth of being alive that he ever got, and it's almost impossible to ignore as an arthouse staple.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.