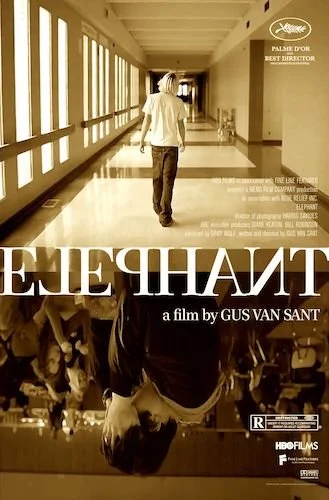

Elephant

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Elephant won the forty eighth Palme d’Or at the 2003 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Patrice Chéreau.

Jury: Aishwarya Rai, Meg Ryan, Karin Viard, Erri De Luca, Jean Rochefort, Steven Soderbergh, Danis Tanović, Jiang Wen.

Warning: the following review discusses sensitive subject matter, particularly the topic of school shootings. Reader discretion is advised.

The early 2000s were a different time, and a crisis like a school shooting would send the United States into a standstill state. No one could ignore the Columbine shooting, and there were so many takes on the tragedy. Film was also involved in the conversation, particularly Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine (Cannes would be reintroduced to Moore a year after the film at the centre of this review premiered). Then you have Gus Van Sant’s confrontational Elephant: one of the most polarizing films for its time. Was there ever the right moment to be this upfront about the topic of school shootings within a narrative? I’d say no. If you want to tackle something this sensitive and triggering, you have to just go for it. However, you also need to have some tact with how you handle the subject matter. Van Sant knew that Elephant — his response to the Columbine shootings — wasn’t going to sit well with everyone, so he had two mindsets whilst making it: be as truthful as possible, but also be considerate to those affected by the event.

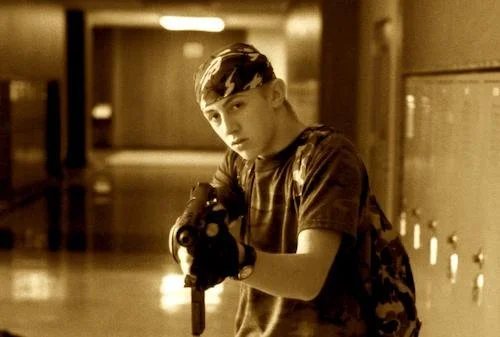

Elephant is made up of many still and long shots, and filmed in a way that is as raw as possible. It doesn’t have any major performers: only newcomers and unknowns. This is definitely a slice of indie cinema more than anything, and Van Sant could have easily opted to be more disingenuous with the Hollywood route (after the release of Good Will Hunting and all). Instead, we get moments before disaster to be familiar with those who will kill their fellow students, and those that lost their lives on what should have just been just another ordinary high school day. We don’t get any answers as to why the killing spree takes place, but there could never be any proper justification, anyway. Van Sant isn’t interested in solving what goes on. He wants to humanize those that lose their lives, or their loved ones, to these merciless acts. We suddenly forget about the tabloids, numbers, and responses to these massacres. We are reminded of the absolute extremities of them. We never forgot how awful school shootings are, but Elephant goes the distance with connecting us with the actual extents of these acts; to be students that are unaware of what is to come; to have life cut short while you’re figuring out your own identities; to not even know how to prevent this from happening to you in the moment.

Whilst a conversation no one wants to have, Gus Van Sant’s Elephant is a tricky-yet-thorough look at school shootings and their awful nature.

Elephant is named after the Indian allegory about the blind men that all approach different parts of the animal without knowing what it is, only to believe that the other men are lying because they are each experiencing their own unique experiences. Perhaps what Van Sant is trying to get at here is all of the different angles of the same crisis: these different perspectives and storyline are all still attached to the same heinous act of murder, no matter how you look at them. Maybe you won’t get anything else out of Elephant outside of exposure, and that certainly isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. It’s the kind of film where you probably know exactly how you will feel about it before you even see it: if you don’t want to view a film about school shooters, you likely won’t feel differently after watching it. I also have to say that one watch is all you need if you are interested. What new information will you get out of a film that is driven by its wide stances on a particular issue, especially with how direct it is? Elephant is merciful enough to not give much attention to the actual shootings themselves, but rather the lives lost, the aftermaths, and the frightening empty spaces in between. I would say that Elephant is a film of its time (a response to a national story), but it sadly is far too relevant today, considering its home nation refuses to do anything to protect the lives of innocent youths.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.