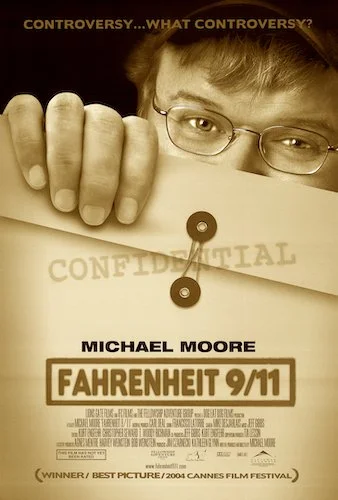

Fahrenheit 9/11

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Fahrenheit 9/11 won the forty ninth Palme d’Or at the 2004 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Quentin Tarantino.

Jury: Emmanuelle Béart, Edwidge Danticat, Tilda Swinton, Kathleen Turner, Benoît Poelvoorde, Jerry Schatzberg, Tsui Hark, Peter Von Bagh.

2046. Oldboy. Tropical Malady. Clean. Life is a Miracle. These are some of the films that were submitted to be a part of the Palme d’Or competition for 2004 (so was Shrek 2, so take from what what you will). The jury, led by Quentin Tarantino, opted for a film that’s far from bad, and yet it feels like one of the most puzzling top winners in Cannes history. Amidst this pack, the jury selected Fahrenheit 9/11: Michael Moore’s documentary that dissects the hidden corruption within the George W. Bush administration and their involvement and reportedly true intentions surrounding the Iraq War (as well as the wrinkles in the coverage of the September 11 attacks carried out by al-Qaeda). I can see why someone may be affected or a supporter of a film like this, but for it to be awarded the highest honour at Cannes feels so… strange. Even worse films that have won the Palme d’Or feel more in-line with what Cannes typically champions, but maybe that’s the beauty of the award: there is no limitation. Maybe the jury just wanted to select a film that represented their sentiments when Dubya was up for re-election, but Tarantino swears that the film was chosen strictly via artistic merit: as the best film of the pack.

Judging the film as such, I can’t say that Fahrenheit 9/11 is a poorly made film. The editing of so much footage into these manic-yet-clean montages is actually astonishing to watch, and it’s the element of the film that feels the most like a Palme d’Or winner; for the most part, motion pictures are fundamentally the assembly of footages into stories or messages, and Fahrenheit 9/11 carries out this foundation with such flair. The incessant usage of popular music to really nail points (more or less on the nose, to be honest) feels like a bit much, but then I can’t help but wonder if Moore’s filmmaking wasn’t a precursor for the metaphysical films with broken fourth walls and points to give (The Wolf of Wall Street, The Big Short, these sorts of works): pop culture and political flurries of information told in a way that is constantly engaging. Whether you agree with Moore’s points or not, you have to admit that the guy can assemble a film at least reasonably well.

Despite being a peculiar choice to win the Palme d’Or, Fahrenheit 9/11 is still a strongly made film, whether you side with it or not.

Sure, Fahrenheit 9/11 is extremely one sided, but Moore clearly had his audience in mind (he’s not exactly the kind of voice that will renege on his own viewpoints to try and appeal to many viewers). Besides, Moore was clearly furious and wanting to get down to the bottom of wishy-washy behaviours stemming from the White House, and clearly many Americans wanted to get some answers as well. Much of what is revealed in Fahrenheit 9/11 is commonly discussed in hindsight now (possibly even because of the film for some), so it doesn’t carry the same punch that it had when it was in theatres (I recall the zeitgeist of this film being everywhere: rivalling even The Passion of the Christ as the go-to cinematic experience of 2004). Still, to watch Fahrenheit 9/11 in 2022 is to see a filmic essay that has a few (okay, many) jabs betwixt and between many points that are meant to alert the American public, and the film holds up at least with how it is made.

Depending on what you believe, the film may act as a “I-told-you-so” when seen now. I’m not sure if future generations will be watching the film as their first point of reference to learn about the Bush administration, but I think that this would be the rare instances where new viewers will be completely bowled over by what they find. It’s a slim demographic, but I’m sure it will make Moore feel chuffed with the possible everlasting impact that Fahrenheit 9/11 may have. With the proclamations of inaccuracy and bias that Fahrenheit 9/11 and Michael Moore have been plagued with since this film (and others of his) came out, the legacy here is marred a little bit. I won’t go down this political rabbit hole, as I try not to alienate some readers that may agree or disagree, and I’m also not sure enough about what Moore allegedly got wrong. What I will say is that Fahrenheit 9/11 was made with scorn for the Republican party, yes, but I honestly feel like Moore was trying to make a film for the people (even his biggest enemies). You don’t have to like it, of course. But this was a bold film made during a time of healing and reflection, as history may have been destined to repeat itself for another four years. It spoke loudly enough to audiences, and even the Cannes jury. It may not carry the same wallop, but, boy, was it massive upon release.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.