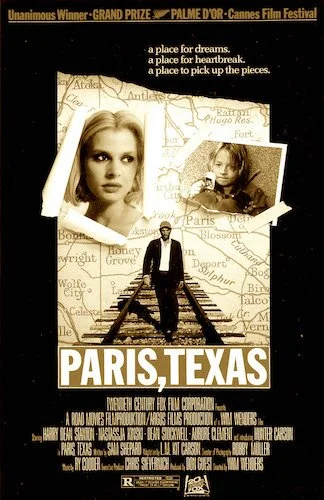

Paris, Texas

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Paris, Texas won the twenty ninth Palme d’Or at the 1984 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Dirk Bogarde.

Jury: Franco Cristaldi, Michel Deville, Stanley Donen, Istvan Dosai, Arne Hestenes, Isabelle Huppert, Ennio Morricone, Jorge Semprún, Vadim Yusov.

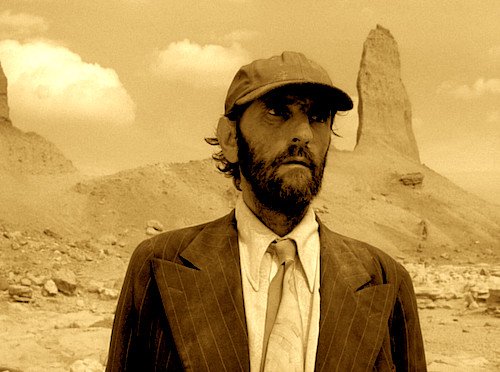

There was a time where Wim Wenders’ masterful angel epic Wings of Desire was his de facto opus, but I feel like audiences are gravitating towards Paris, Texas in this day and age. I prefer the former myself, but only by molecules. I get personally very moved by Wings of Desire in a spiritual way, despite not being a spiritual person myself. It makes me go where my soul usually would never tread. However, I think people love feeling seen, and Paris, Texas is much more rooted in reality and the kinds of heartaches we actually face. The image of a broken man hobbling across an endless desert actually encapsulates all of us at some points in our lives. We know exactly what this feels like. This is how Paris, Texas starts, and you’ll feel recognized instantly. In the internet age, I feel like we are overly seen but not understood. That isn’t the case for Paris, Texas. It’s aesthetically sublime enough that it’s easily shareable online. It taps into all of our hearts at such a rapid pace. In the way that Kanye West’s 808s & Heartbreak or Joni Mitchell’s Blue may have been loved upon release but have become magnets for despondent souls that need that catharsis in the cold internet age, Paris, Texas has aged tremendously; it has pinpoint accuracy when it comes to nailing the sensation of lostness.

Cannes felt this way instantly by unanimously rewarding Paris, Texas the Palme d’Or (a feat that is quite rare in the history of the festival). Everyone on the jury agreed that this was the best feature of the festival, and this says a lot when you have the range of the colourful and fun Stanley Donen to the maestro of emotional resonance Ennio Morricone. I don’t think that Paris, Texas contains a little bit of everything, but it definitely has a little bit of everyone within it, and not a single viewer won’t find themselves here. Part of that comes from the highly sympathetic leading performance by Harry Dean Stanton: an actor who could pull at my heart strings with almost any performance. I’ll never forget how I felt like I was watching my own father in Pretty in Pink because of how pure Stanton was to watch. If he had my eyes watering with a John Hughes film, you can only imagine what he’s capable of with his career-best work in Paris, Texas. As Travis Henderson, Stanton begins the film off without a single word. He wanders around mutely in a nearly comatose state: broken by the events of life itself. By the end, he only talks: he even talks on behalf of his loved ones (particularly in the iconic solo conversation). He comes full circle, but he’s forever the stone faced man on the outside: a statue plagued with regret and loss.

Harry Dean Stanton has never been better in Paris, Texas.

Travis exiled himself for years, separating himself from his family. He seemed to be a disciple of the American Dream: the very one that most of us lie about to ourselves to make the sting hurt a little less. He needed to get away from it all, and he evidently was too far removed from society. He’s found barely functioning and unable to muster a word; eventually he can only string the letters of one word, “Paris”, together. His brother, Walt (played by Dean Stockwell), believes this call to be a request for an excursion to France, but it’s far simpler than that. Travis wants to return to Paris, Texas, not to escape even further, but to confront his deepest fears. I feel like it’s only partially honest that Paris, Texas is deemed a road film because we only travel so much during the motion picture, and it’s more of an exploration of one’s consciousness than a traversing of the United States (although we do get that as well). Road films get such a bad reputation anyway. Paris, Texas is so much more. It genuinely feels limitless.

Two major factors keep the already-fascinating premise impossible to turn away from, and their names are L. M. Kit Carson and Sam Shepard. Shepard feels like the constructor of the backbone of Paris, Texas, with a simplistic story sewn together by the kind of all-American poetry that takes your breath away. Carson allegedly placed the major finishing touches on the film: the kind that have made it a timeless classic (especially the iconic climax that feels nearly like a daydream and of a different film entirely). The two forces combined result in a painfully stunning tale of soul searching and reparations. I mean, think about it. Did Paris, Texas mean anything to you until you watched this film? Unless you grew up there, have passed through it, or have stumbled upon it, likely not. Now, it means everything. It is one of the most iconic locations in cinematic history. That’s the power of this film and its story: purpose was found within the unexpected (you can easily say the same thing about Travis as well).

The ending sequences of Paris, Texas are some of the most astounding in all of film.

It seems silly to say that such a small little film could go so far, but that’s because the right people were selected for each job (I now also must bring up Nastassja Kinski, who shows up exactly when she needs to and carries the weight of the most emotional revelations within her reactions). There’s one last piece of the puzzle to bring up again: Wim Wenders. When Wenders misses, you can at least appreciate where he was trying to go with his films (something like Until the End of the World comes to mind). When he hits his targets, I feel like he reaches untapped, eternalized material that not many other filmmakers can find. His majestic filmmaking feels so effortless with Paris, Texas: one of the great scaled-back, independent films of all time. It is nothing short of magnificent, but I’m guessing you know that, already.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.