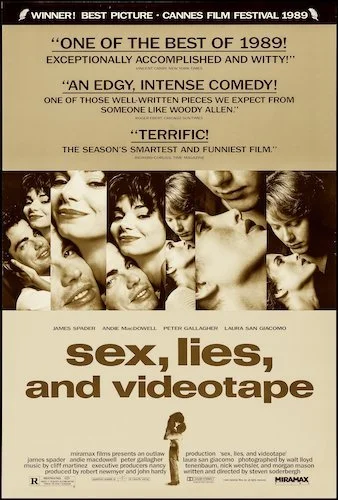

Sex, Lies, and Videotape

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Sex, Lies, and Videotape won the thirty fourth Palme d’Or at the 1989 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Wim Wenders.

Jury: Christine Gouze-Rénal, Claude Beylie, Georges Delerue, Hector Babenco, Krzsztof Kieślowski, Peter Handke, Renée Blanchar, Sally Field, Silvio Clementelli.

Intimacy can be converted from vulnerability, and Steven Soderbergh proved that he understands the barest fundamentals of our fight-or-flight responses with his very first film Sex, Lies, and Videotape: a masterpiece of the indie film circuit. Something stood out about this film and resonated with the Cannes jury of 1989, especially amongst the works of masters alongside it. Still, it was not only a groundbreaking Palme d’Or winner for its time (Soderbergh was the youngest solo director to ever win the award at 26), but it remains an archetypical winner as well. Chances are when you think of the award, something like Sex, Lies, and Videotape comes to mind. So what clicked into place for this film? Why was this the right setting and the right time? How did Soderbergh jumpstart the then-newest era of the independent film circuit into a new league it had never experienced before? Again, it boils down to the auteur’s mastering of our barest natures. It’s easy to call him an expert of mimicry in hindsight, considering how many styles of film he has bested (and with such varying budgets to boot).

The title alone places three of the most unguarded human experiences together. During the act of consensual fornication, souls are impuissant as passion takes over; we don’t have any fronts when our bodies connect as one. When we are lied to, we have a strange juxtaposition of our defences instantly rising whilst our comfort levels are completely depleted. How could I be betrayed like this? I trusted this person, and they deceived me straight to my face! Then, there is the act of voyeurism and being watched, and this is possibly the most exposed we’ll feel. We can have conversations in a simple, traditional way. As soon as we’re on camera and our every move is being tracked and recorded, we have to watch our every move and second guess what we do next. All three pieces of the film’s title evoke a different kind of sensitivity within us; euphoria; disappointment; uncertainty.

Sex, Lies, and Videotape is an excellent genre bender, but it is permanently vulnerable.

Sex, Lies, and Videotape almost feels like a David Cronenberg film (and it’s not just because James Spader is here, although I will use this opportunity to bring up how the eclectic actor’s presence in any film in the 80s and 90s is an instant draw for me, as he picked almost exclusively interesting projects). This is likely because of the tiptoeing and discomfort of the entire motion picture, and it starts right at the opening (naturally). We meet Ann, whose distant husband is cheating on her with her own sister (classy). A friend of husband John’s is Graham: a peculiar fellow that seems to mean well, and yet there’s something “off” with him. We learn soon enough that he has a collection of videotapes that he recorded himself: his hobby is to interview women and ask them about their best kept secrets, regrets, and fetishes. You’ll learn very quickly that Sex, Lies, and Videotape feels like our world but also as a projection from an alternate reality. People don’t function this way: not out in the open. This film feels like our inner consciousnesses having a conversation. It’s understandable but still very alien.

Soderbergh has this persistent, unwavering vision, as if the film is staring directly at us with such eerie certainty. We cannot help but gaze back. I could feel my soul levitate a little bit, as if I was being extracted from my own body into this frigid world to join the other lifeless, aimless spirits on screen. If anything, Sex, Lies, and Videotape almost feels like a filmic purgatory. This is where we go when we die. Life is kind of as we once knew it, but we are consciously emaciated versions of ourselves. We wander around, bump into one another, and have confrontations, either sexually, empathetically, or abrasively. You can analyze the film this way, or boil it down to Soderbergh reducing us to our most primitive forms. We mate. We crave. We attack. Within a contemporary lens, Sex, Lies, and Videotape makes these archaic values feel foreign, but they’re us at our most animalistic. Humans appear very strangely in Soderbergh’s debut, but we are bizarre creatures after all.

Humans act very distantly and coldly in Sex, Lies, and Videotape.

Don’t get me wrong. The film isn’t all unapproachable. It’s still quirkily funny, as it uses humour as a front to be heard. This is just how Soderbergh operates: without boundaries. Whether you want to label the film a skewed comedy or an unorthodox drama with strong comedic relief is up to you. To me, the film feels like we’re watching one of Graham’s tapes for the entire duration: like we’re spying on what we shouldn’t be seeing. Some of it may be amusing, sure, but I find the film’s strengths to lie in its placement of its audience outside of their comfort zones. I love being challenged or displaced. Sex, Lies, and Videotape makes me feel lost within familiarity, and that’s not easy to pull off (let alone from a first time prodigy of a filmmaker). While irrelevant, I also love how Steven Soderbergh never rested within one genre, style, or voice. As one of the most prolific and varied directors of all time, he continued to push himself in so many ways (let’s also bring up how he has such control over his films, including even cinematography and editing).

Why he felt like Sex, Lies, and Videotape was where he wanted to start, I’m not sure. What I do know is that it was the perfect move. Everyone was wondering who this kid was and what more he had to say. He seemed to have perfected his craft instantly. Hell, many working filmmakers today can’t pull off the examination of self that Sex, Lies, and Videotape evokes. Whatever the case may be, Soderbergh was prepared to break rules and not answer to anyone but himself, and it’s this kind of revivifying filmmaking that got him instantly noticed by Cannes and the world in its entirety. Not many films feel as human-yet-inhuman as Sex, Lies, and Videotape.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.