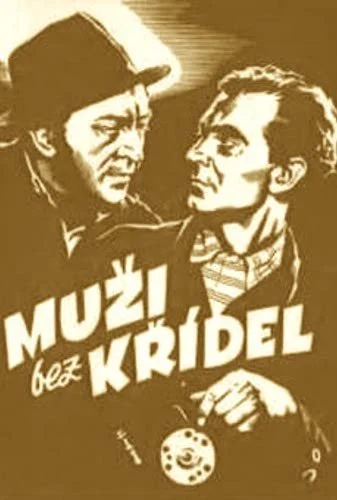

Men Without Wings

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. This is a Grand Prix winner: what the Palme d’Or was originally called before 1955. Men Without Wings won for the 1946 festival and was tied with ten other films.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Georges Huisman.

Jury: Iris Barry, Beaulieu, Antonin Brousil, J.H.J. De Jong, Don Tudor, Samuel Findlater, Sergei Gerasimov, Jan Korngold, Domingos Mascarenhas, Hugo Mauerhofer, Filippo Mennini, Moltke-Hansen, Fernand Rigot, Kjell Stromberg, Rodolfo Usigli, Youssef Wahby, Helge Wamberg.

Of all of the war films to make a splash at the first full Cannes Film Festival (then known as the International Festival of Film), Men Without Wings feels like the most narratively intricate. Taking into account the assassination of Schutzstaffel-Obergruppenführer and General der Polizei Reinhard Heydrich, and the aftermath of Czechoslovakia, Men Without Wings is a heavy affair that dives into the darkest depths of humanity. We see this via two generations: the adults who have to face these atrocities head on (in the form of Petr Lom), and the children who will inherit this awful state of the planet (young Jirka, whose entire family has been slaughtered). All of Czechoslovakia is having to answer for the assassinations, even if these citizens don't have anything to do with them.

There's a third character named Marta, who is actually an informant for Germany (unbeknownst to Lom), and you will quickly see how this element will tie everything together in Men Without Wings. At an impossibly brisk eighty minutes, this is the shortest Grand Prix (or Palme d'Or) winner ever. The film has some interesting story going on, especially with this interwoven approach to warfare and survival. However, you're not going to get the scope of what you may be accustom to, especially when the film is so easily comparable with other war based films that won the Grand Prix this very year (I don't need to go further than Rome, Open City). Sometimes, you don't always need that size. Men Without Wings is a little more sculpted, perhaps to the size of just a bust when it should have been an entire statue, but it's remarkable for what it is.

The featuring of generational doom in Men Without Wings was substantial for many viewers watching this film after World War II.

And that is a precise yet startling personal tale of destruction. There isn't much hope in Men Without Wings, but the teensiest dose comes at the end of the picture, albeit with a desire of what would hopefully come to Czechoslovakia (and the world): solidarity and freedom. Released after World War II was over, Men Without Wings can be appreciated in hindsight: this justice will come. Despite the narrative limitations, I do admire that this film represents one out of countless voices that were striving to be heard once war was over and the coast was (hopefully) clear. It's tough to critique many of these works because their existences are justifiable. The world needed contextualization and relief. Men Without Wings may not have gone the distance like its contemporaries, but it at least provided Czechoslovakia's angle of what they went through during modern history's worst hour (and for that alone, it is worth checking out).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.