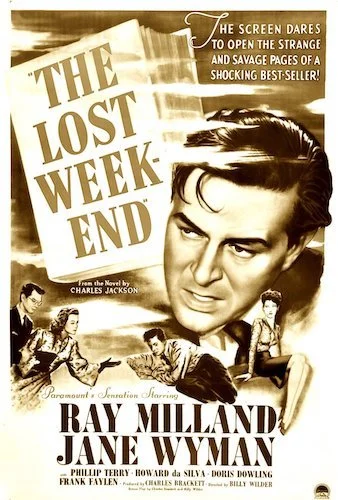

The Lost Weekend

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. This is a Grand Prix winner: what the Palme d’Or was originally called before 1955. The Lost Weekend won for the 1946 festival and was tied with ten other films.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Georges Huisman.

Jury: Iris Barry, Beaulieu, Antonin Brousil, J.H.J. De Jong, Don Tudor, Samuel Findlater, Sergei Gerasimov, Jan Korngold, Domingos Mascarenhas, Hugo Mauerhofer, Filippo Mennini, Moltke-Hansen, Fernand Rigot, Kjell Stromberg, Rodolfo Usigli, Youssef Wahby, Helge Wamberg.

I’ve written about The Lost Weekend before when covering every Academy Award Best Picture winner, but I will use any opportunity to discuss it again. As a massive fan of Billy Wilder (a top twenty filmmaker, and definitely a top ten writer) and films noir (does this site’s name give that away?), this film speaks to me so much. Now, it is one of only three Best Picture winners ever to win the Palme d’Or (or, in this case, the Grand Prix: the original name of the award), but the year it won kind of seems like a no-brainer: how could a great film not win when it was literally tied with ten other films? How could it not win technically after it won Best Picture (because of its distribution in Europe)? Then again, there is a silver lining that comforts me: this was the sole representative of American cinema amidst the eleven winners (each nation had its own sole submission), and you won’t find many films from the United States as good as this one in either 1945 or 1946.

When we look at the lineup that is Wilder’s filmography, you have many undeniable masterpieces; Sunset Boulevard; Double Indemnity; Some Like It Hot; The Apartment; the list can keep going. The fact that The Lost Weekend deserves to be a part of this conversation is a testament to two things: how great of a film it is, and also how underrated it is within Wilder’s legacy. Wilder was great at blending genres (particularly comedies and dramas), but he could also make one hell of a noir, and that’s what we have here. In a style where lone wolves fight uphill battles to get down to the bottom of situations, we instead have a speedy tumble through a downward spiral in a descent of alcoholic madness. Ray Milland plays Don Birnam: a writer who is working on his next project when he succumbs to a four-day bender instead. Unlike some of Wilder’s other films, there is nothing funny here. This is purely tragic.

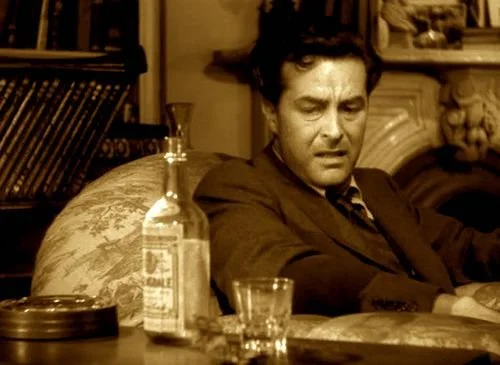

Ray Milland’s many faces of desperation make The Lost Weekend a harrowing watch.

While Wilder’s direction and writing (alongside his usual co-writer Charles Brackett) make The Lost Weekend a riveting look at mental traumas, addiction, and existential dread, it is leading star Ray Milland that makes the film as frightening as it is. It’s one thing for the crew to set up shadowy shots at canted angles, elaborate sets that are hyper-detailed and feel like they are looming in on you, and the occasional surprise. It’s Milland that makes all of these fears come to life: as if we are actually witnessing someone withering away via substance abuse. I genuinely believe he has the sweats when he is dripping from his forehead: not that water has been placed upon his brow. Milland looks like he is in excruciating pain here: it is a performance for the ages. The Lost Weekend may have tied with ten other films for the Grand Prix, but Milland was the sole — and the first — winner of Cannes’ Best Actor award.

To house this singular performance, Wilder needed to go fully dark himself, and we’re lucky that he did. I don’t think that he’s the kind of director or writer that would lose sight of what tones are necessary with his projects, but I’m still happy that he didn’t feel any inkling to lighten The Lost Weekend at all (outside of the safe-ish ending, which I blame on Hollywood more than anything). Wilder is almost a completely different director when he submits himself within the most pessimistic corridors of society: as if he funnels the imagination he would originally save for a sharp quip and places it within another scary image or idea. It’s fun to see what comedic lines he can come up with, but it feels so much more fascinating to see where his dark side is willing to go; he sheds light on the joys of being human, but his arguments against our worst capabilities as individuals and as societies are just as noteworthy.

Billy Wilder is such a great filmmaker when he opts to go dark, and The Lost Weekend is evidence of this.

It makes sense that The Lost Weekend was the American film to make the biggest splash at Cannes (enough to win multiple top prizes), because it strived to be so anti-Hollywood (even within the industry’s confinements). Outside of its sole sugar-coated decision (likely to allow the film to even get made), The Lost Weekend is as real as self destruction could be in an American 40s film. It’s mostly a one-man show, but what a show it is: you get to know this poor soul that is suffering and trying to rectify his own life. There’s no femme fatale, outside deviancy, or underlying plot: there’s only his own personal demons keeping him at bay. That’s a noir character study if I have ever seen one: it’s almost a prototype of neo noir, if I do say so myself (the exploration of how far the classic style can go, and how it can be broken yet honoured). The Lost Weekend is indicative of modern day psychological thrillers, and with this in mind it holds up incredibly well in a contemporaneous sense as well. This film is still under-seen, and I cannot swear by it enough.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.