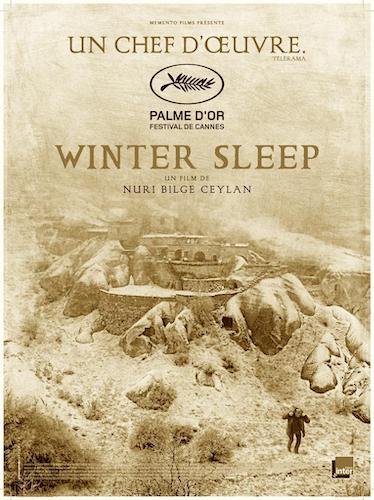

Winter Sleep

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Winter Sleep won the fifty ninth Palme d’Or at the 2014 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Jane Campion.

Jury: Carole Bouquet, Sofia Coppola, Leila Hatami, Jeon Do-yeon, Willem Dafoe, Gael García Bernal, Jia Zhangke, Nicolas Winding Refn.

In what ways can you portray your motherland as intricately as possible, especially if you have some grievances you wish to air? Nuri Bilge Ceylan seems to have cracked this code with Winter Sleep: his seventh film to date, and arguably his most well known release (outside of, say, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia). In general, Ceylan is a strong filmmaker whose approach of genre conventions always feel so fresh and uniquely his own, so heading into Winter Sleep for the first time, I wasn’t sure what to expect outside of something different. One of the longer Palme d’Or winners at nearly three hours and twenty minutes, Winter Sleep is cold, distant, and sterile, yet it is an absolutely gripping watch. It almost feels like a great novel that you cannot put down, and you know not much is happening in a big way all of the time, but you’re also enticed to find out what happens next.

Aydın is a landlord/hotel owner who used to be a part of the arts as an actor: he is clearly disillusioned now, but that may not be entirely his fault. Life places us in predicaments we don’t necessarily prophesy. However, Aydın does get his creative fix via writing for the regional newspaper. He lives with his wife Nihal, who is slowly falling out of love with him. There are a number of other prominent characters, including a tenant that is struggling to keep up with his ret bills and turns to addiction, and Aydın’s sister who is at a crossroads in life. The use of a hotel at the centre of Winter Sleep allows people to come and go, so we can pop in and out of each subplot that surrounds Aydın and his own connections to Cappadocia: a village in Central Anatolia where the film takes place. It’s Ceylan’s way of covering more ground in this grim fable.

Nuri Bilge Ceylan is able to provide many perspectives on the states of the working class in Winter Sleep.

Ceylan wrote Winter Sleep with his wife Ebru, and together they come up with one hell of a screenplay. Winter Sleep is a very dialogue-heavy film, but I barely even noticed the entire two hundred hours. These are fairly real conversations and confrontations going on, and the camera rarely turns away from these juicy moments. I wouldn’t call Winter Sleep an invasive film, but I still felt like an onlooker that can feel the breath of disturbance on my neck. These are all the citizens of a divided nation, as Winter Sleep is a tale of classes. Not only that, but the main characters themselves are trying to figure out their own places in the system, and these personal quests alone are often the points of conflict in this labyrinthian narrative.

Visually, Winter Sleep feels exquisitely barren. Bronzes, greys, browns, and steel blues paint the entire picture here, and it almost feels like you’re watching a series of illustrations (especially because of the glacial speed of the camera’s movements, and the patient editing). All of these visual elements add to the film’s low key tone. There’s enough here that feels whimsical even amidst all of the dread and frigidness, like Ceylan has a sense of wonder to his craft. All of this is important for Winter Sleep’s gradual downward spiral, as hidden intentions get brought to the forefront, and ignored problems become the focal points of misery. The plot in Winter Sleep festers, and it slowly seeps into you precisely when it needs to.

Winter Sleep looks as cold as it feels: a distanced look at a neglected system.

Nuri Bilge Ceylan is speaking entirely from experience when he made Winter Sleep. This film is his documentation of the current state of Turkey and its varying identities when viewing the working class: those that are successful and don’t want to ever be demoted to the lower class, and the poorer citizens that are finding it challenging to keep afloat. Here, all walks of life are united in one key setting. Their dissimilarities are put on full display. However, what unites everyone is also in plain sight: desolation. No matter where Winter Sleep goes, you know that it won’t be a happy ending. It’s just far too bitter in a hibernal sense. You know there’s no promise or room for growth here, and yet the entire motion picture is captivating. At the end of the day, Ceylan is a little cynical about modern day Turkey, but you know that Winter Sleep comes from a place of love: a question of “how did we get here?”.

That hidden passion, buried deeply underneath all of the lovelessness, is the final ingredient that makes Winter Sleep great. This is a conflicted portrayal that begs to take on Ceylan’s mixed feelings. Perhaps he’s speaking more about the dreadful ways of the world, and he just so happens to frame his film in Anatolia: on this note, Winter Sleep is highly relatable. I don’t think we’ve seen the best from Ceylan, either. I’m at a point of my Palme d’Or research where I’m close to the present, and I’m going to predict that Nuri Bilge Ceylan may be on the short list of directors to win this award twice. Trust me. It’s likely.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.