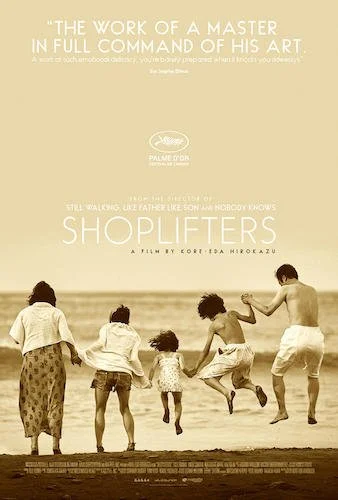

Shoplifters

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

This review is a part of the Palme d’Or Project: a review of every single Palme d’Or winner at Cannes Film Festival. Shoplifters won the sixty third Palme d’Or at the 2018 festival.

The film was selected by the following jury.

Jury President: Cate Blanchett.

Jury: Chang Chen, Ava DuVernay, Robert Guédiguian, Khadja Nin, Léa Seydoux, Kristen Stewart, Denis Villeneuve, Andrey Zvyaginstev.

I feel like part of Hirokazu Kore-eda’s plan with his greatest film was to bother you from the get-go. You are bound to be irked with such a judgemental title like Shoplifters (or Shoplifting Family, which is the literal translation of its Japanese title). You may be expecting a film more cynical than the one you get, especially because you learn quickly that the Shibata family is a loving one, and that they rob from stores only because they need to survive. Maybe this instant bitterness you’ll feel is the exact mindset Kore-eda wanted you in: you instantly are defensive towards the protagonist family and all of the sacrifices and unpleasant things they have to do in order to get by. You hate the stigma right away. Now you area ready to keep watching Shoplifters: a moving, tough watch that will hopefully be talked about for years to come.

The Shibatas are struggling to make ends meet, especially after father Osamu gets injured and cannot work anymore (they were already having major financial issues; this was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back). Everybody in this family does what they need to do in order to put food on the table, ranging from working in a sex club to actual shoplifting. Their lives are affected even further when a young child, Yuri, is locked outside of her house and neglected late at night. The Shibata family offers to take her in and nurture her temporarily; once they realize that she has been abused, they try to give her a better life. It’s all about perspective: Yuri is of a more fortunate family but is miserable. The Shibata family lives with extreme poverty, but they love one another and will do anything to support each other. What is better for Yuri?

The contrast between living situations is what carries Shoplifters: a study of what is authentic domestic happiness.

Of course, this circumstance sets things off course, as now Yuri’s family is trying to look for her. In the mean time, Yuri is assimilating quite nicely, and is being taught how to shoplift and be a part of the operation (although she is also educated on the family belief that only items in stores are to be stolen, as they don’t belong to anyone personally yet). This is only the tip of the iceberg, as the ethics within the Shibata family also begin to go haywire, with members going too far with their schemes, and others starting to question what it’s all for. Shoplifters starts off more cohesively sound than it ends, and that’s not a complaint about the film. Rather, its a compliment about how magnificently Kore-eda allows his structure to come crumbling down. You can point fingers at the Shibata family for getting sloppy or complacent. I blame the system that has failed many families like this one: with good hearts driven to sin in order to not die.

Naturally, Shoplifters is all about moral compasses, and you’ll be thrown in for a loop towards the final act of the film. You’re left to deal with the biggest questions of the entire picture, particularly about what people deserve, and what should have actually happened (if life was fairer). Did the system get the justice right here? I would argue no, and Kore-eda likely feels the same way. There’s nothing we can do. Many lives are bound to be unfortunate, and it’s because we prioritize wealth and stature over our own wellbeing. In the way that society scorns the Shibata family for resorting to stealing to live, should we not be as bothered that society as a system steals our own lives and reduces us to embarrassing, disregarded nothings? Did anyone else within Shoplifters even give the Shibatas a chance at anything? Watching the family itself break apart is the most saddening part of the film, because it is at this point that the most promise available — their bond — is now compromised.

For being such a sad film, Shoplifters possesses a lot of warmth as well.

While all of the drama is fascinating, it is the surprising warmth that makes Shoplifters stand out even further. There is a lot going on, and most of it is unfortunate, but seeing the family do their best to try and help one another (with the occasional moment of sincerity and joy) is the icing on top. As bad as everything gets, this happiness (which is already slim in quantity) experiencing friction feels like the last blow: nothing is good anymore. Shoplifters came out at an interesting time, as it is one year before the slightly similar Parasite, but it was evident that Cannes continues to be of the same mindset (considering that two Dardenne brothers films also won the Palme d’Or, amongst many other winners): civilization is its own worst enemy. We should be trying to help one another, not champion the downfalls of our fellow human. I guess there’s only so many ways that artists can express this sentiment, and only so many times that Cannes can try to get the word out by celebrating these works.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.