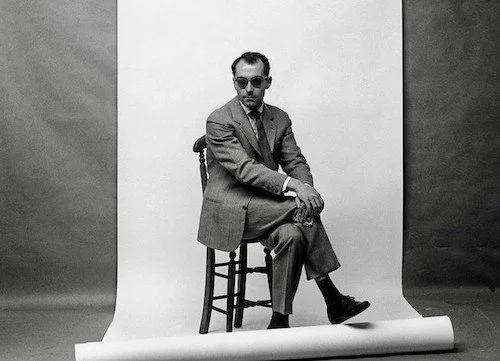

Jean-Luc Godard: Ten of his Greatest Films

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Jean-Luc Godard was one of the most direct visionaries in all of cinematic history. As a member of the iconic Cahiers du Cinéma team (writers and critics that translated over towards actually making films and creating what would become the French New Wave movement), Godard was transfixed by film as a language. How could we say things differently? Why are we abiding by rules instead of creating our own? Godard set an unreachable bar when it comes to experimental cinema, especially during his unparalleled run in the 60s. Many filmmakers strived to copy what Godard achieved in one experiment, and the latter auteur would be heavily involved in his next hypothesis and accomplishing additional unorthodox realizations in the meantime. Not many directors were as successful with their unconventional practices, especially with this kind of turbulence.

Now, Godard is sadly no more. He passed away at the age of 91 this past Tuesday. While the world lost an immense amount of talent that morning, cinema will definitely be the same. You see, Godard left his mark many decades ago. His works will always be studied in university and adored by cinephiles. His many films will forever inspire and challenge us. If there's one thing that his death has reminded me, however, it's that there truly wasn't anyone like Jean-Luc Godard. There still isn't. There likely never will be. You can strive to travel off the beaten path all you want, but following in Godard's footsteps is the last thing he would have done. He represented complete individuality whilst playing the same game all other filmmakers did. His impact will forever remain, but that won't mask how much he is painfully missed. Here are ten masterpieces from the late Jean-Luc Godard.

A Woman is a Woman

Godard rarely indulged in what the rest of the film industry was doing, but such an occasion would look like A Woman is a Woman: this off-centre look at music-based romantic comedies of the early 60s. It was an early exercise with colour for Godard, and he made sure to leave his mark on this front with a tryst drenched in the most vibrant colours. It’s strange to see Godard channelling fun through the cinematic medium, but that’s part of his oeuvre and milieu: he forever found new ways to make normalcy feel fresh again.

Alphaville

While films noir were on their way out, Godard sent the style off with a graceful tribute. Alphaville is dangerous but sleek, and, in typical fashion, Godard doesn't set out to tick off every box of the genre. You can tell that the budget was slim, but Godard's expertise supersedes any lapses other inexperienced filmmakers would have left exposed. Alphaville isn't just full of shadows: it's murky by design. Unlike most classic noir films, Alphaville makes you feel like you're watching a film from another galaxy, and that's a rarity when directors abide by genre conventions.

Bande à part

This quirky flick about delinquency marches to the beat of its own drum, and the film plays out as rebelliously as its main characters act. There is one moment of solace with the iconic dance sequence that feels like it will never end, as this trio of misfits find their own harmony within an environment that has completely given up on them; they loop their choreography again and again with zero attention directed at them. Quentin Tarantino named his production company after this film, and it's easy to see why: it is one of the most inexplicably stylish films of its time.

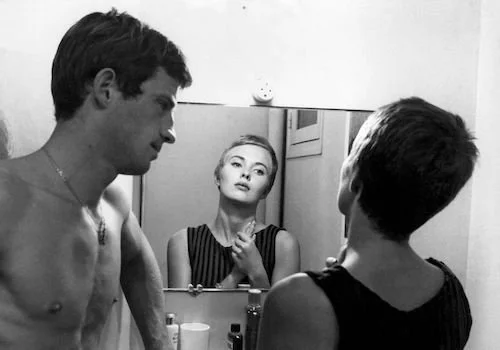

Breathless

Where Godard’s legacy started. Not many directors — especially with such strong filmographies — can claim that their first film was their best, but Breathless truly is the finest film of his career (as well as all of French New Wave). Driven purely by the ambition to make a feature film, Breathless isn’t held back by its qualms (low budget, the need to shave moments for time, Jean Seberg being out of place): it is enhanced by them (raw storytelling, postmodern editing, and the sense of an American it-girl clashing with the grit of the Parisian streets). Breathless is filmic jazz, and effortlessly singular.

Contempt

Godard’s films had a certain cynicism to them, but he did occasionally display empathy at the forefront of his pictures. Contempt feels like his answer to cinema as a whole, after a couple of years in the industry (and not from the outside as a critic for the medium). A filmmaker grows more and more distant from his wife while working on a film (with the legendary Fritz Lang making a cameo as himself playing a bit of an onlooker of both the production and this hurdle). Godard — who also pops up in the film — allows film to gaze upon film again and again whilst questioning what it’s all for: the blood, sweat, and tears, in a medium that hardly picks up on any of those fluids for us to truly connect with (although with Contempt, we’ve never been closer).

Goodbye to Language

Perhaps one of the more interesting takes on the whole 3-D film craze that occurred during the 2010’s, Goodbye to Language was one of Godard’s final stabs at a conventionality in film. This experimental film is highly abstract as a story and even less comprehensible visually, but you’ll never see a film like it again (particularly one exquisite moment where the three dimensional illusion actually “breaks” before your very eyes, with you being able to close each eye and see a different image for a brief moment). Godard was the best to pave his own path even in his old age; Goodbye to Language was his penultimate film before the final The Image Book.

Histoire(s) du cinéma

While Godard was prolific for a majority of his career, he devoted more time to this filmic essay than anything else. Histoire(s) du Cinéma took around ten years to complete, is four hours in length, and is easily one of the most fragmented experiences you may ever have. Nonetheless, this feels like the holy grail that Godard was constantly in search of: a way to completely turn film on its head in a way that feels entirely untapped. With the appropriation of images and sounds to weave tapestries of film, Histoire(s) du Cinéma takes the familiar and creates something profound and provocative with it. This is filmic art at its most visceral.

Pierrot le Fou

Godard never operated with uncertainty, but Pierrot le Fou feels like one of his most confident releases. With the same levels of fourth-wall-breaking lunacy and postmodernism of his finest works, Pierrot le Fou struts where other Godard films would waltz: its loud colours, sharp editing, and sarcastic melodrama all make for a highly flamboyant affair. While Godard typically employed style in his works, Pierrot le Fou almost feels hyperbolic as it lands each and every moment with a direct punch to your gut or heart. There’s a reason why this particular film resonates so deeply with cinephiles: it stands out from most packs.

Vivre sa vie

Breathless was Godard’s first film, and A Woman is a Woman saw the director testing his luck with rom coms. Then, there’s Vivre sa vie: his best attempt at making a straight forward drama/tragedy (of course, in his own way). One of cinema’s most devastating affairs, this masterclass performance by Godard veteran Anna Karina (who appears in the majority of the films on this list) is framed by the malices of society, the animalistic ways of humanity, and how the world will forever be unforgiving (perhaps a point Godard wanted to make clear time and time again). If you’re tired of Godard’s mind, Contempt and Vivre sa vie are the strongest portals to his heart.

Week-end

Week-end is very much a Godardian work through and through, but it is a neat exercise in how the late auteur toyed with his own signature traits; this feels more like a gradual descent towards filmic insanity than an all-out onslaught of cinematic naysaying from start to finish. I feel like this film resonates because of how “welcoming” (a term I will use loosely, given the dark storyline of a murder scheme) the film feels at first, before Godard plays all of his cards. While other Godard films may feel more avant-garde or challenging, Week-end is undeniably a trip that must be experienced.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.