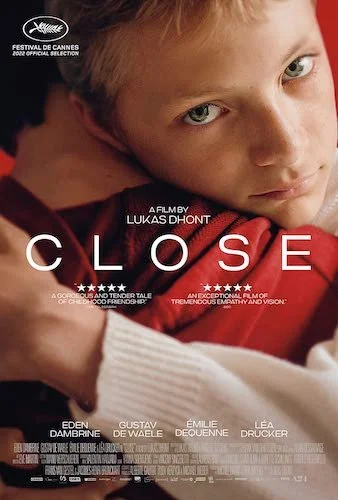

Close

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Warning: minor spoilers for the film Close are in this review. Reader discretion is advised.

When introducing the film in Toronto, director Lukas Dhont said that his latest feature, Close, was a story he has been wanting to tell for years (one can assume his entire life). He commented on the relatability he shares with the feature, and it’s one that breaks my heart once I finished watching this magnificent achievement. Close is a work of LGBTQ+ cinema in the same way Beau Travail is: not by what you see, but by what you don’t see. Contradictory to its precise name, Close is the examination of the unfortunate distance one feels from another, and it truly affected me with Dhont’s summary in hindsight: is the longing what the Belgian director has felt ever since he was a child? My spirit feels crushed for him. Close is guaranteed to shake you up as well, and I can easily liken it to the noteworthy manipulation of nostalgia and time found in the recent film Aftersun (if you liked Charlotte Wells’ debut, Close is for sure for you).

We begin with elementary school pals Léo and Rémi, who have bonded quite closely over the course of the summer break. There’s no public space with more scrutiny than the schoolyard, where their friendship is instantly questioned and antagonized by other students who cannot keep their nose out of the business of others. Are Léo and Rémi gay? The real question is: why does it matter to anyone else? Regardless, Close as a feature never pries into their relationship, no matter what label it can receive. The important thing with Close is how others define them to the point of suffocation, and the feature goes in the direction of where society dictates it to go. Life itself is like that, sadly: many are forced via bullying or intolerance to rethink who they are. As Léo and Rémi are at that shapeable age of thirteen (when they are figuring out their own identities), they are pressured into at least considering what they hear. How do they respond? Close shows us, and it isn’t pretty.

The central relationship in Close is well established so quickly, so its deconstruction works right away.

Close establishes its central friendship so well from the very beginning that it can focus on its devastating aftermath really early into the film; I never felt like I was missing key information, either. This is truly effective because of how much Close is invested in the distancing between two people that care for one another, as if this yearning is the central purpose of the film and not the love (platonic or romantic) that came beforehand. It is important to know about this absence because it is what makes Close as vital as it is: it is a masterclass in telling a story with as little as possible, and with the void of information rather than the insistence of it. I have yet to see Ghont’s Girl (believe me, I am now eager to get around to it), but it is clear that he is already a director that knows how to break the rules and make his own structures to great effect. He is one to watch for, and I would get a start on his filmography right away now that something as strong as Close even exists.

The emptiness of Close gets bigger and bigger as it progresses, and it feels like an entire weight of the world is crushing your chest by its final act: a realization that there is no turning back. The very final sequence is the ultimate punctuation point: a revisitation to this place during the same time of last year, noticing how different it is. Without giving much away, there is a powerful breaking of the fourth wall: we are acknowledged as the onlooker, aware of the gap that is impossible to fill. We can’t act as the replacement either, and Close knows it as it progresses after its momentary lingering. Close is titled not solely after the tightness of two conjoined souls but the nearness of being able to rectify the past: we really do get close to seeing hope at times, but it isn’t enough.

Close toys with the emptiness left in the story as one of its most important assets.

Close is one of those late-game awards season submissions that cuts it close, but it is just as worthy as the best of the best this year. In fact, had I seen it sooner, it could have easily made my top ten of 2022. This is such a strong example of showing and not telling (something so many filmmakers need to learn), as all of Lukas Dhont’s latest feature is felt and not orchestrated. I insist you catch this film regardless of how the awards season pans out, because Close is so much more than wins and nominations (no matter what all of the awards season marketing leads you believe). I do implore you to see it though. Don’t let time pass by and allow a film as astonishing as Close get neglected by the more thunderous noise of the season: it feels like a cinematic gift from a rising auteur whose name you will likely know for years to come.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.