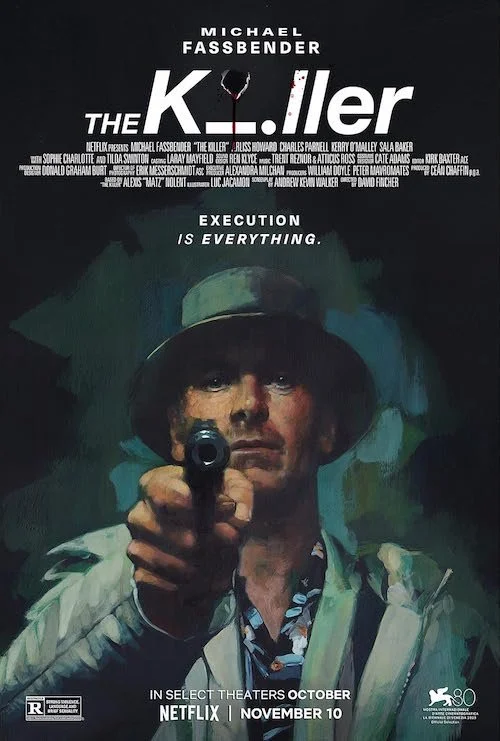

The Killer

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

From the first sequence — which seems to last around twenty minutes (or so it felt) — I was wondering where David Fincher’s latest film, The Killer would go. Not because I found the film ponderous or inert, but rather because I knew this patient, methodical look at crime and death wasn’t what many would sign up for. A Netflix release, The Killer will slink in and out of theatres quickly enough before it is available worldwide via our devices: the same kind of accessibility that Fincher and screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker (who has worked with the auteur on films like Seven and as an uncredited script doctor for The Game and Fight Club) despise. We see the many steps it takes for the unnamed hitman (he goes by “The Killer”) to fulfill his job, and yet the world Fincher and Walker show us is one where people are confined to their homes or favourite stomping grounds, where delivery services give us everything we need and we fester in our own thoughts, needs, and greed. The Killer starts off the film waiting on his mark in a lengthy sequence, but he entertains us via his intrusive thoughts acting as narrator the entire time. He’s courteous enough to give us his company as we, the viewers, grace him with ours.

As The Killer progresses and we follow the assassin from destination to destination, all we see are lives of both privilege and lethargy (and the two not being exclusive, either). Despite how secluded we all are, we do not live a life of anonymity because of the many footprints we leave from the Amazon purchases we make, the food we get delivered, and the very few places (gyms, restaurants) we frequent just to feel alive; to feel useful; to feel connected. How different are we from The Killer, who is confined to one point and left to his own devices in order to accomplish what he needs to do? The difference is that he is forced into this spot. What is our excuse? Yes, The Killer is really about a hitman whose world gets turned upside down once his latest job goes wrong, but it is also about so much more: disconnection. Fincher has always been fascinated by the human experience, what moral choices we make in order to save ourselves or others, and the ennui of life and how we become fixated on the mundane to try and re-experience life again. The Killer seems like Fincher’s most boilerplate film to date on paper, but it’s a culmination of all that he has learned thus far as a filmmaker. Zodiac was loved upon its release but is now considered one of the director’s finest achievements and a highlight of twenty-first-century cinema. I don’t expect The Killer to get quite the same reputation, but don’t let the labels “solid” and “typical” fool you: The Killer may experience a similar fate where its adoration comes later on.

Michael Fassbender is exceptionally chilling in The Killer: one of his finest roles to date.

What would a film about a lone character be without a fantastic lead? Michael Fassbender plays The Killer, and it has easily become one of his finest roles. He’s nearly as still as he was in top android form as David 8 in Prometheus and Alien: Covenant, but here we can tell he is a real human being: a broken, psychotic, traumatized human being who has lost almost all faith in the world. He rarely speaks in the film, but he thinks a lot, and we hear all of his internal monologues (delivered as meticulously as Fassbender acts as his character). The amount he is able to say with just his deadpan face alone is extraordinary. While the rest of the cast is great as well, Tilda Swinton is another example I must bring up because of how captivating she is in such a small amount of screen time; if the Academy Awards know a thing or two, even her brief, ten-fifteen minute role deserves a nomination. On that note, seeing both stars sitting across from each other could only remind me twelve years later how irritating it was that neither got nominated back in 2011 for Shame or We Need to Talk About Kevin: two of the finest performances of the 2010s. Perhaps all can be rectified with a film that brings both superstars together to jaw-dropping effect.

As Fassbender strings us along, we get a story about a hitman who wants out of this life while being tossed one last curveball: a personal attack that means he’s not finished just yet. The film results in a hyper-calculated exposition of events where The Killer either plainly tells us what is on his mind (like when he is forcing himself to not feel sorry for someone who is in distress, for instance) or by showing us without having to over explain. I particularly love an earlier scene where The Killer is staying at a hotel next to the airport. He orders room service not for the food but specifically to have a glass — which he places on the handle of the door leading to the hallway — and a plate cover that gets placed on the ground right beside the door. We never have to see this situation unfurl, but we know his bases are covered: should an intruder come in, he will be woken up from the noise and have enough reaction time to respond. Before I ruin the magic of The Killer by explaining every little detail, just take my word for it: this film is full of similar sentiments in almost every single shot.

This gets to the point where you may feel like The Killer becomes predictable, and it’s perhaps too well thought out. I would agree if you watch this film as a thriller film where an assassin has to make it out of the picture alive. Instead, view The Killer as a dissection of the mind of such a person whose entire life is based on the ending of other lives. You may be disappointed if you want action, closure, and purpose to these killings. You’ll feel enriched if you allow The Killer to take the wheel and dip you into daily routines and thought processes. Through these avenues you will feel sick, anxious, and even, dare I say, entertained. At times, The Killer (in typical Fincher fashion) is even darkly comedic, but that’s because jokes are all about timing. Throughout this film, I couldn’t help but think of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in the West, where the Italian legend toyed with pacing, pauses, and anticipation in order to create the strongest bouts of tension you can find; he believed more in the buildup more than the payoff. Fincher has a similar blueprint here, where we are left to dial in on the small audible cues, The Killer’s lingering thoughts, and the moment where the gun will finally fire. There were moments here where I felt anxiety more than I have from any film in quite some time: I really felt I was there with The Killer.

The Killer is full of tension, even though the story goes to places you expect it to.

It wouldn’t be a Fincher film without amazing intro credits, and this film wastes no time cutting right into its opening montage of assassination techniques filtering in and out of your field of vision. It’s also when you are quickly reminded that Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross are back yet again for another Fincher outing, and their score does not disappoint; from cathartic pianos to humanize what we feel to screeching frequencies to snap our brains and place us in The Killer’s shoes. Another frequent collaborator, director of photography Erik Messerschmidt, brings back an old motif of Fincher’s from Zodiac (another similarity between the two films): the use of blue and yellow to dominate cinematography and the balance (or lack thereof) between daytime and nighttime, and the hazy colours of the sky in between both phases. Yet another Fincher regular, Kirk Baxter, keeps up with The Killer’s precision by matching his speed and efficiency with some blistering editing. In short, there are many things The Killer should be nominated for, and I will be damn well pissed off if it garners very little come the awards season.

It’s hard to compartmentalize The Killer for those who haven’t seen it, but it feels equal parts Le Samouraï and John Wick: the zen, calm approach to slaughter via the characterization of a fragmented mind of the former, and the brooding vengeance plot at all costs of the latter. The film demands to be seen on the big screen, but I can foretell a certain irony that will come from watching this film via Netflix at home: a certain level of judgment based on the predictable habits of twenty-first-century living. There’s no way that Fincher is equating laziness or vulnerability to the acts of a murderer, but there is a conversation surrounding how susceptible we are in a world where we are brought closer and closer than ever before. We can’t get much closer to the assassin at the forefront of The Killer than this, and yet we still never find out his name or what he’s all about (despite how much he actually opens up to us). We do find out that he is obsessed with The Smiths (whose songs are sprinkled all over this film, and I can’t complain about this one bit: The Queen is Dead is forever in my top ten favourite albums of all time).

Outside of this one side (where he has joy through songs whose lyrics are typically morbid or depressed), we learn nothing about this man. Even when he finds freedom, his own life is mundane and soulless. And yet he will be no different than the world around him despite what lengths he took to get there. The Killer is a plea for us to appreciate what we have, which is easier said than done in a civilization where we are pigeonholed into what we can do and how we can go about it. The freedom of choice is an illusion. Just try not to be so jaded. It’ll be tough to feel anything but resentment during a Fincher film, but we’re used to that by now. I’m just glad that The Killer is much more subtle about the fight for personal freedoms and choice than Fight Club is. Here, we get asked not just where the protagonist’s life went so wrong, but where society does as well, despite the fact that the world around our antihero is never painted to be anything but normal. Now that is unsettling. The Killer is all about choice, particularly how we choose to live our lives. In the case of the assassin we follow, we get given various opportunities where he can alter his own fate. The biggest question at the end is whether or not this actually amounts to anything for The Killer. Are our lives as routine (albeit with far fewer fatalities)? We’re forced to sit on that thought either at home or in a theatre once The Killer ends as quickly as it began. And just like that, the film is gone without a trace, and we are left with the uncomfortable aftermath: a stylish, exhilarating film that forces us to confront the worst aspects of the world (from murder to self-destruction via existential surrender).

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Ryerson University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.