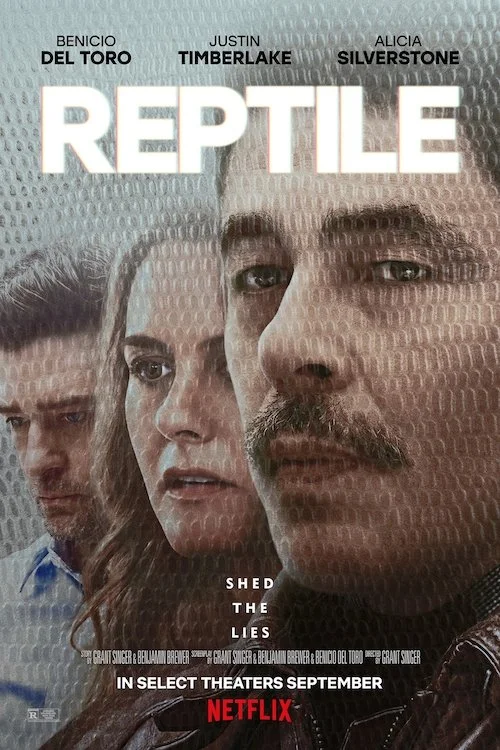

Reptile

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

When Benicio del Toro’s Detective Tom Nichols is inspecting the kitchen of a murdered victim and her widower boyfriend (Justin Timberlake) and is toying with the hands-free faucet, the music continues to get more and more anxious with frantic strings cueing for something more than a silly punchline (Nichols turning to his cohort and quipping “I love this kitchen”). This is precisely when I recognized that Reptile has roughly two hours of runtime left and that this may very well be a tonal disaster. Well, Grant Singer’s debut film doesn’t fulfil this dreadful promise, but it doesn’t exactly pick itself up from out of its funk at any point. No matter how deep we get into the central investigation or how much more we learn about Nichols as a person, Reptile kind of just exists. It has an identity: a lethargic, dreadful lull. However, it doesn’t really feel alive at all. I love some films that feel cold and cynical, but they at least have a pulse. Reptile doesn’t really have that either. It is cut to have beats, shot to have interesting images, and acted to create a pessimistic environment, so there is clear direction present throughout. Nonetheless, Reptile just disappears as quickly as it is presented.

Nichols is tasked with solving the crime of a murdered real estate agent and is helped by his loving wife Judy (Alicia Silverstone, who really should take on roles like this more often because she’s quite good in them). The deeper Nichols goes into this case, the more he learns about the complexities of his own reality as a detective, as well as the criminal dwellings of this part of Maine. Suddenly, the target is squarely on Nichols’ back: he can either walk away or risk his own life to get the answers he craves. The film is presented so stoically from the start that the ending feels as cryptic as the beginning. While this makes Reptile somewhat of a Pandora’s box waiting to be opened, it also renders the film a bit stale when it should be burrowing itself under our skin. The conclusion isn’t abstract as much as it is obnoxiously sudden to the point of feeling unsatisfactory even if you can make heads and tails of its resolution; I personally believe I was able to follow along, but I’m still not happy with the hastiness of those ending credits rushing me out of the theatre (or at home for those of you watching via Netflix).

A strong performance from Benicio del Toro can’t save the sterility of Reptile.

The main reason to watch through and through is Benicio del Toro, who also co-wrote the screenplay with Singer and Benjamin Brewer. In the leading role, Del Toro is fascinating in such a gruff way. He doesn’t emote much, but he also doesn’t have to, and he’s one of the very few people to get away with this in such a grey film. I’m not sure what contributions to the screenplay Del Toro provided, but I can see the natural magnetism and concern that he brings to the film. Even if we feel lost, we are led by him and huddle up to his side as he traverses into the unknown. It’s almost an antithesis to his character in Sicario where we are brought into the depths of hell through him. Here, he’s learning when we do as well, but he’s fascinatingly fearless. I could have watched him for another hour; then again, in a film where it already felt like four hours instead of just over two, maybe I’d rather not.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.