Maestro

Written by Andreas Babiolakis

Bradley Cooper isn’t a naturally gifted filmmaker whose capabilities come so effortlessly to him. No. He works hard for this title. Other auteurs can whisk together a compelling sequence because this talent can be found in their very core. Cooper was previously seen as the actor who paved his way to get to the point of prestige. As one of the very few noteworthy alumni of the Actors Studio to truly make it in the twenty-first century, he endured typecasting in films beneath his skillset. Eventually, he became the beloved star taken quite seriously since at least 2012 when his chops in Silver Linings Playbook could no longer be ignored. He has put himself on a similar course as a filmmaker. He seemed to strike gold instantly with his umpteenth remake of A Star is Born, but it’s clear in hindsight that he didn’t simply make the film and see where the wind took him. So many actors turn to filmmaking and flop as soon as they begin; some have middling-yet-noble results; Cooper seemed like a natural. After watching his latest film, I need to rescind this mindset but not because I think he is a poor filmmaker by any stretch. After years of production, gestation, and build-up, Maestro is a film that is perhaps slightly overcooked by a passionate director not trying to experience burnout after the success of his debut. I’ll never fault a director for trying too hard when they could have had the opposite problem: zero effort whatsoever. It’s clear that Cooper is midway through his trajectory towards something undeniable with this latest release, and while Maestro isn’t perfect, I say we let him continue to cook.

Once again, Cooper also stars in his directorial effort, this time as famed American composer Leonard Bernstein (in what may be his strongest performance to date, particularly because of how defined his voice and mannerisms are and yet how restrained his emotions as the late music legend are; it’s a great balance that a keen director and an even smarter actor can inhabit). Despite how much focus is on the bigger of the two names, Cooper seems to insist that this is truly a picture of actress Felicia Montealegre (Bernstein’s wife and frequent collaborator), and this is proven by the top billing of Carey Mulligan (who stars as Felicia). The film begins and ends with Leonard, but it’s easy to view him as the conductor of the picture (especially with Cooper acting as both star and director, who is essentially conducting the film) as he conjures up his story of how he met and loved Felicia. While Cooper’s depictions of Leonard’s fascinations with his wife are sweet, Maestro tends to drag temporarily within its second act, but I also cannot feel good about myself condemning these passages of pure love, especially since they precede the turmoil and tests that are to come. Sure. Maestro doesn’t really get into the artistry of its two subjects quite enough, but it at least picked a lane and stuck with it (their romance); the film doesn’t get painfully schmaltzy about this storyline either, which is an additonal plus.

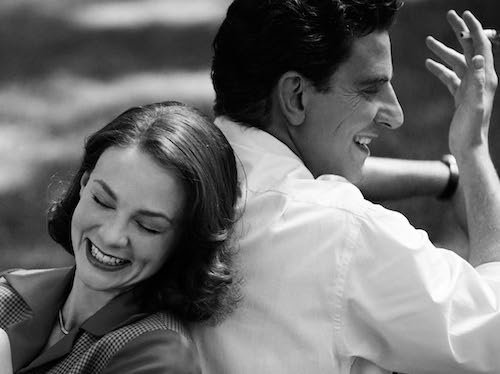

Carey Mulligan and Bradley Cooper shine with career-best performances in Maestro.

We spot Lenny towards the end of his life reminiscing about his late wife with a richly colourful shot. It isn’t long before we dive into black-and-white and shoot back decades before, as all of the years of love the couple shared are shown through these rose (erm… grey?) coloured glasses. Once we get far enough into their story, the film returns to colour, we jump ahead a few years and see both Lenny and Felicia older and drifting apart as a couple. The film doesn’t settle for melodrama and tabloidy nonsense, but it also doesn’t opt for in-depth, nuanced depictions of these qualms. Nonetheless, I’d rather have a focused film than a meandering one, and even though Maestro is a bit hazy when it comes to who these two icons were, it is at least specific with how it interprets them as people and as lovers of one another. Maestro is a bit of a romantic fable using real people as its protagonists, and viewing it as such reveals Cooper’s care and prowess on the subject. If you’re expecting a Leonard Bernstein biopic through and through, you won’t really get that here (I don’t think even a four-hour film can contain all of the important details of his life, and it’s clear that Cooper prevented himself from getting this carried away with such a fruitless endeavour).

It’s clear that Maestro was retooled and retooled and retooled in post by a director who just wanted this film to count. Some passages drone. Some information feels missing or incomplete. When Maestro works, however, you see what Cooper was opting for all along, as the film certainly possesses some of the strongest scenes of the year (particularly the six-and-a-half minute sequence where Leonard Bernstein famously conducts the London Symphony Orchestra at the Ely Cathedral in 1976: a sequence where I could almost feel my heart stop beating because I was floored by this exposition of direction and acting by one lone, committed, passionate individual). Maestro certainly begins and ends strongly as well with some electrifying depictions of artistry and passion captured in such creative ways (the earlier scenes through theatrical artistry, and the latter via unhindered adoration). If Cooper gave his all both in front and behind the camera here, then Carey Mulligan followed suit with a career-best turn as Felicia Montealegre. She feels so humanistic here and she never chases the milieu of an iconic figure’s stature. In the final act of the film towards the end of Felicia’s life, my heart wept for her not because the film forced me into feeling sad but because Mulligan is so believable in such a raw, pure way. The film’s goal was to view Felicia Montealegre through Leonard Bernstein’s eyes, and Mulligan takes this mission right past the finish line and then some.

I know Bradley Cooper was gunning for Maestro to be his masterpiece, and in ways, it feels like some of his greatest ideas and executions as a filmmaker and star. I almost love the fact that it doesn’t quite get as far as he wanted it to for the following reasons. Firstly, I am starting to think it’s almost realistically impossible for a perfect Leonard Bernstein biopic to exist in any capacity: some figures are just too large for this medium, and I wish some directors would learn and accept this. Secondly, if anyone came close to pulling this off, it feels like Cooper had as good of a shot as there could possibly be, and even then Maestro — while flawed — is still a really good end result. This could have been produced and refined even more to the point of sterility and at least that wasn’t the case. Cooper didn’t get his magnum opus this time, but he got damn close, and he delivered a beyond admirable effort for such a tall order. If anything, this feels like just another step in his career as a director. A Star is Born wasn’t beginner’s luck despite it being a stronger film overall, because some of the ideas in Maestro are riskier (and some of the payoffs are stronger; again, I cannot get the cathedral scene out of my mind). This is just yet another part of the career of an artist who never gave up fighting and learning. Some visionaries are naturally gifted. Some put in the due diligence and hard work to get to where they need to be. Bradley Cooper is still on his way, and if Maestro is a weaker film in his filmography, this only means promising things for the artist who refuses to quit.

Andreas Babiolakis has a Masters degree in Film and Photography Preservation and Collections Management from Toronto Metropolitan University, as well as a Bachelors degree in Cinema Studies from York University. His favourite times of year are the Criterion Collection flash sales and the annual Toronto International Film Festival.